Super Neologisms

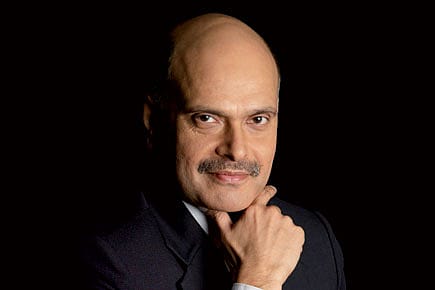

In the age of Lord Leveson, few media barons would like to be called the 'Rupert Murdoch of' any place. Raghav Bahl, the founder and former head of Network18, has no such compunctions. The jacket of his new book proudly embraces the epithet 'Rupert Murdoch of India'. This desire to buck the bien pensant is not, however, evident in the rest of the book. An attempt at analysing the key drivers of global change, Super Economics is too much in thrall to the received wisdom of the moment. While Bahl paints on a broad canvas, the picture that emerges is rather too familiar.

Global politics today, Bahl argues, is defined 'not by Superpowers building formidable arsenals but by interconnected Super Economies building a robust global exchange.' What does this neologism stand for? 'Essentially', Bahl writes, 'it is a large and prosperous or prospering country that uses economic leadership to effect change in the world.' A Super Economy, in his definition, must account for 15- 20 per cent of global GDP or grow at near double-digit rates, as well as rank as a leading global trade partner. Territory, a young and innovative workforce, good infrastructure, a strong currency, powerful military with nuclear capability, and 'soft power' all go into the making of a Super Economy.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Unsurprisingly, Bahl identifies the United States as the 'undisputed leader of the Super Economy age.' Europe and Japan are deemed too old and lethargic to make the cut. Among emerging markets, only China qualifies so far. Russia is on the decline. South Africa is 'too small… and too remote to exercise much global influence.' Brazil is 'unlikely ever to become more than a fringe Super Economy, akin to France in the Twentieth Century.' India, by contrast, is 'in exactly the right place at the right time to fulfil its long-held promise and ascend to the pantheon of Super Economies.' No matter what ails the Indian economy and state: Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who represents 'the change that people of India have long sought', is at hand. The global situation is colourfully summarised by Bahl: 'US is the stalwart Super Economy, Japan and Europe fading Super Economies, and China the scrappy challenger, India is the sleeper Super Economy.' Having laid out that framework—others have called it geo- economics—Bahl veers off in another direction. His real interest, it seems, is in trying to figure out how to deal with the rise of China. 'Can China be simultaneously welcomed into the global community and effectively constrained?' The key, he believes, lies in an alliance between the democratic Super Economies of the US and India. I write 'believes' advisedly, for there is no effort to show how any of this follows from his premises. In a string of non sequiturs, Bahl asserts that 'India and America are on track to develop an alliance of the ages.' Together they can help countries 'facing Chinese aggression' such as Bhutan and Vietnam. What's more, they can also help 'defuse the hostile eruptions that keep cropping up in such places as Syria, Iraq and Ukraine': never mind the fact the US is the trigger for much of these 'eruptions'. This Indo- US alliance, according to Bahl, 'will resemble a cross between the US-UK and US-Japan relationships' of the 20th century. So, Indians are supposed to be thrilled at the prospect of becoming a cross between a poodle and a vassal?

What can be said of this fantasy? Very little except that Bahl himself seems unconvinced by important parts of his story. In his more lucid moments, he concedes that 'Beijing isn't eager to incite actual military conflict in Asia's waters'. 'The Age of Super Economies', he notes, 'engenders a much 'warmer' kind of interaction, where engagement is essential'. What then is the rationale for an Indo-US military alliance? Alongside a military alliance of democracies, Bahl envisions a Pacific-Asia Free Trade/Investment Alliance—anchored by the US and India. He is apparently unaware of the fact that US is putting just such an arrangement in place—the Trans- Pacific Partnership which pointedly excludes India. Indeed, far from working with the US to counter China in the 'United Nations, global climate and trade organizations', New Delhi has far more in common with Beijing on these issues.

Bahl concludes on an optimistic note. The 21st century, he claims, could be 'one of the most harmonious and prosperous in history.' He also ends with his biggest non sequitur: 'It all depends on Modi.' Let's hope he is right.

(Srinath Raghavan is a senior fellow at the Centre for Policy Research)