Subversive Truth

VICTORIAN NOVELISTS HAVE always taken the idea of the novel quite literally: a form that invites reappraisal and transformation. Charles Dickens was constantly changing his mind as he was writing and simultaneously publishing sections from Oliver Twist in Bentley’s Miscellany. In ‘When Colour is a Warning Sign’, the second ‘anti-novel’ collected in Subimal Misra’s This Could Have Been Ramayan Chamar’s Tale, Nirmal Gupta, publisher of Eikhon, a Calcuttan little magazine, expresses his own ambiguity towards Misra’s work: ‘it is quite difficult to suddenly come to any conclusions regarding you […] In your writing there are no such things as sequential events, it appears outwardly to be only floating images […] the question of outright rejection does not arise because some aspect or another haunts me.’

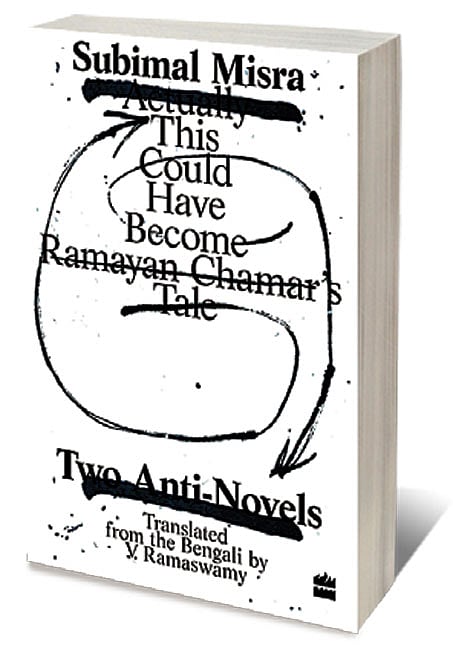

V Ramaswamy, who has produced a stupendous translation of Misra’s ‘anti- novels’, places the ‘anti-establishment’ author at the tail end of the Hungryalist Movement and ventures farther in history to cite Misra’s forebears: Jagadish Gupta, Manik Bandopadhyay, Kamal Kumar Gupta, and Amiya Bhushan Majumdar, who were ‘parallel’ to writers canonised in Bengali literature, like Tagore. By terming Misra as antithetical to something, as opposed to being ‘parallel’ to it, both Ramaswamy and Misra suggest a confrontation and a conflict. Janam Mukherjee’s foreword to the collected anti-novels asserts: ‘[Misra’s] writings [continue] to push at the boundaries of the middle-class bourgeois mores, structured towards a pernicious and predatory socio-political order.’

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

In the eponymous first anti-novel, the narrative of Ramayan Chamar, a Bihari Dalit working at a tea plantation in North Bengal, forced into a ‘system akin to slavery’, and murdered early, is one filigreed with images surfeit in babudom and a ‘delusion of radical leftism’.

In the seams of Misra’s own narrative jumps, the deep gulfs of Bengali livelihoods — ‘pimp and gentleman, professor and idiot, babu and dalit’ —are laid bare. The word, ‘scissors’, appear throughout the text not only to signify the layered divisions within and beyond it, but to symbolise separatist ambitions of the disenfranchised that interrupt the narrative: ‘We, the poor people, offspring of the disfavoured queen’s womb—the country’s become independent while we’re left to forage cow-dung’.

Although Misra sets a manifesto for the Anti-Novel in a preamble subtitled ‘Subimal versus Subimal’, in which he decries ‘literature [that] begins to speak in a single mould and tune’, his ideology is perhaps more ably embodied in the second anti-novel where he expresses a desire for ‘many-more-things’ in a story. The reader, who desires to ‘become one with the times’ seeks to find truth in these many-more-things that only the novelistic form can convey. A novelist’s duty is to be a trustworthy exhibitor whose text is ‘simultaneously story, history, proclamation and personal diary’. Misra’s text is quite superficially just that: an amalgamation of newspaper clippings, soliloquies, and vignettes arranged in a postmodernist mosaic.

‘When any stationary or moving thing is presented directly,’ Misra claims, ‘its actual visage cannot be captured.’ Misra’s anti-novels are as much a reinvention of the novel, that has been congealed and commodified into a methodised, stationary, inert ‘cultural object’, as a critique of the bhadrolok, the bourgeoisie, whose totalitarian impulses have alienated and antagonised the rest in Bengal. Much like Nirmal Gupta, I too have found it difficult to extract something absolute from reading Misra, constantly changing my mind about how I feel about his prose. But, I have come to this realisation: as an anti-establishment writer, more fertile in Bengali little magazines than the mainstream (as this very translation)—a nod perhaps to his Hungryalist forbears—Misra’s anti-novels might be novels after all: changing our minds about each of the many-more-things through a reappraisal of form and substance.