Style & Substance

MUMTAZ IN A flaming orange readymade sari, stitched in a way to allow for easy movement, singing to Shammi Kapoor in Brahmachari (1968). Zeenat Aman swaying to Chura liya hai tumne in a white jumpsuit in Yaadon Ki Baaraat (1973). Parveen Babi in a glittering, black off-shoulder gown in Namak Halaal (1982). These are the hidden figures of Indian fashion consciousness, enabling women to dream of themselves and their bodies with more confidence, spines straight, shoulders swinging, arms open to the world—and yes, with maybe the hint of a naughty navel and the shadow of a sexy cleavage?

It was no small feat for women who had hitherto seen themselves in fashionable but largely Indian avatars on screen, notwithstanding glorious moments like a swimsuit-clad Sharmila Tagore water skiing in An Evening in Paris (1967), Nanda clad in a clinging negligee gown in Jab Jab Phool Khile (1965), or Sadhana carrying off the skin-tight churidar kurta (less kurta, more dress) with an Audrey Hepburn fringe in the uber posh Waqt (1965).

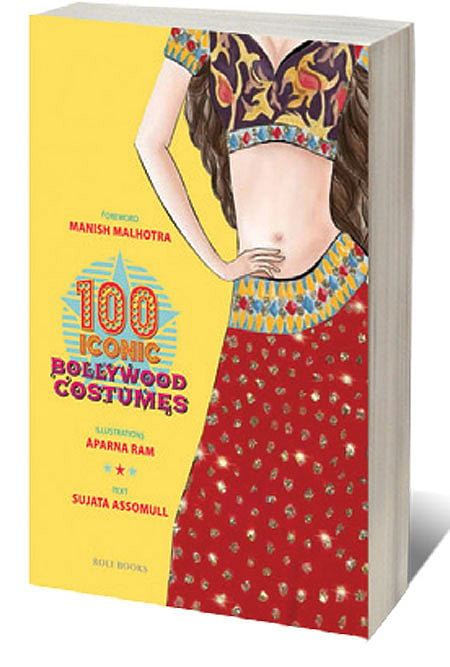

In a world of toned midriffs, competing with beautifully bare shoulders and endless, athletic legs, it is almost too easy to forget these forerunners of fashion. But if you need a refresher course then 100 Iconic Bollywood Costumes is just the book for you. With detailed recreations of the costumes and text that provides context, the book shows us the long line of trend-setting women we come from. And how everything new owes its antecedents to something someone thought of before, from Madhubala’s Anarkali in Mughal-e-Azam (1960) which continues to spawn a million copies to Vyjayanthimala’s trenchcoat and sari combination in Jewel Thief (1967) repeated by Sridevi in English Vinglish (2012); to Nadira’s fashionably functional jodhpurs-and-jacket from Aan (1952) which set the template for how every rich-princess-brought-to-heel should look.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

In excavating some of the most beloved images from our collective past, the book offers its salaams to some of the screen’s greatest stylists. Not just designers Bhanu Athaiya and Mani Rabadi, but Rekha who reinvented herself as a diva. Whether it was her Grace Jones meets Joan Collins shoulder pad dress in Khoon Bhari Maang (1988), or her off shoulder blouse and sari in Kaisi yeh paheli in Parineeta (2005), Rekha has used hair-make-up-costume as armour as much for offence as self defence. Gone was the gawky teenager who was called “patakha” by lascivious producers. In place was a woman, gilt-edged, silver-plated, impenetrable in her blingy bubble. And there she has remained since, in her timeless, off-screen Kanjeevaram-clad style.

But if Rekha is proof of the power and possibility of owning fashion, this book also reminds us of other costumes that have lent themselves to historic moments in Indian cinema. The black bodycon dress with a feather boa worn by the very angrez Saira Banu in Purab Aur Paschim (1970), India’s first nationalistic diaspora drama; the pink kurti and marigold garlands of Dum maro dum in Dev Anand’s hippie-meets-Hindustani-bhai Hare Rama Hare Krishna (1971); and the Kutch-inspired choli worn by Smita Patil as she leads a mirchi-rebellion against the local subedar in Mirch Masala (1987).

Today, when the flash of a navel in Deepika Padukone’s Padmaavat (2018) can still spark a protest, the significance of Mumbai film costume cannot be over-stated. The designers may veer from the ordinary (Kareena Kapoor’s T-shirt-with-salwar style of Jab We Met, 2007) to the over-the-top peacock-feather dress worn by Raveena Tandon in Bombay Velvet (2015), but they are as much influenced by the street as the street is impacted by them. And even though at times the simplest costume is most sensuous and erotic (remember the wet white sari in Ram Teri Ganga Maili, 1985, or the white bedsheet of Sheila ki Jawani in Tees Maar Khan, 2010), the role of fashion in Hindi cinema is always a lead, never a cameo.