Stalin as Metaphor

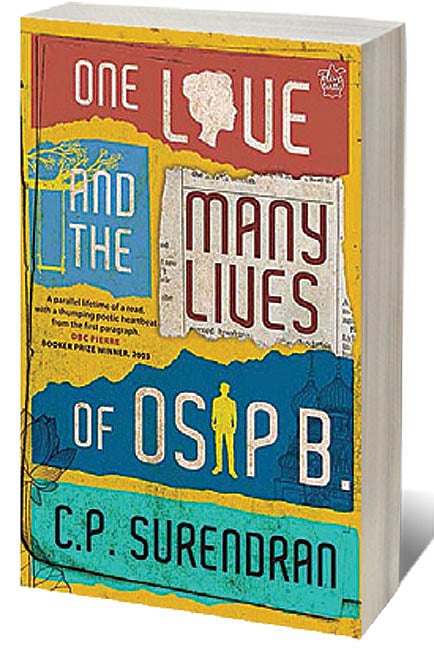

CP SURENDRAN’S NEW novel One Love and the Many Lives of Osip B is centred on the love story of a young adult named Osip Bala Krishnan, who, as a student of a boarding school in the cantonment town of Kasauli, falls in love with his English teacher. Elizabeth Hill, who is of British descent, leaves the school after telling the young man that she was ‘carrying’. With her abrupt departure, Osip B, as if possessed, begins his devious yet successful plot with the help of friends to reunite with her in Britain. The novel captures the journey and thoughts, most of them wild, that pass through the mind of the narrator.

The name Osip was bestowed on the boy by his communist grandfather, and is one of his many contributions to the narrator’s life. Niranjan Menon, the conceptually confused yet ideologically rigid granddad from Kerala with a feisty wife, named him after Osip Mandelstam, the Soviet poet. Mandelstam, we know, was a victim of Joseph Stalin who banished him to a Siberian gulag in 1938. “Often one’s name is one’s fate. One had to respond to the particular challenge that it enjoined upon oneself,” Osip B says as if foretelling what lies ahead. In this multi-layered narrative, what is inescapable is that Mandelstam and Stalin, the victim and victor, share more similarities than the root of their first names, Ioseb (later changed to Joseph) and Osip.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Soviet history keeps surfacing like an allegory for power. Similarly symbolic is how Osip B negotiates his way through his grandfather’s opinions, a constant reminder that the making of today is embedded in the haunting past.

This is a book about love, but it teaches us perhaps a lot more about hate and man’s cruelty towards another in a system where such feelings are legitimised and even weaponised. “Stalin is forever,” says the narrator, arguing that he coexists across centuries and culture. Stalin, therefore, is a metaphor much more than a political figure in this work. Surendran, who is from a storied ‘communist’ family, is familiar with the hunch that the system is plotting its own downfall through excesses, and the sentiment runs deep in Osip B’s imaginations. Unsurprisingly, his protagonist sees Stalinist guile and persuasion, among others, in the bully TV anchor with a resemblance to a living one. The author’s contempt of Malayalee conceit is, as always, infectious.

One can always attribute Osip B’s penchant for the macabre to a condition that he shares with his grandfather, also described here as folie a famille, a shared psychotic disorder. In the process, the writer secures the licence to see and say things otherwise problematic.

The writer is skilled in establishing a connection between the past and present, victim and the victim of victims as well as human behaviour. Osip B says, “Sitting by my grandfather’s bed and watching him die, I would think that the disorder the two of us lived by was not much different from what the digital world sought—validation.”

While readers will definitely enjoy the unforeseen twists and turns in Osip B’s life, marked by intermittent film noir sequences and Hill’s magnificent deception, Surendran takes a look at news events and trends, from the provincial to international, including gentrification and the rise of the right-wing oppressor. He says of one such man, a radio taxi driver, “His freedom comes from his readiness to commit the world to violence, to kill. He is the leader. And the mob. He is the citizen. And the State. The victim. And the victor.”

Osip B is entitled to this candour because he is just out of his teens and is given to hallucinations. By arming himself with such a character and thanks to his fecund imagination, Surendran has made a profound political statement couched in the art of the novel.