Speaking in their own Voices

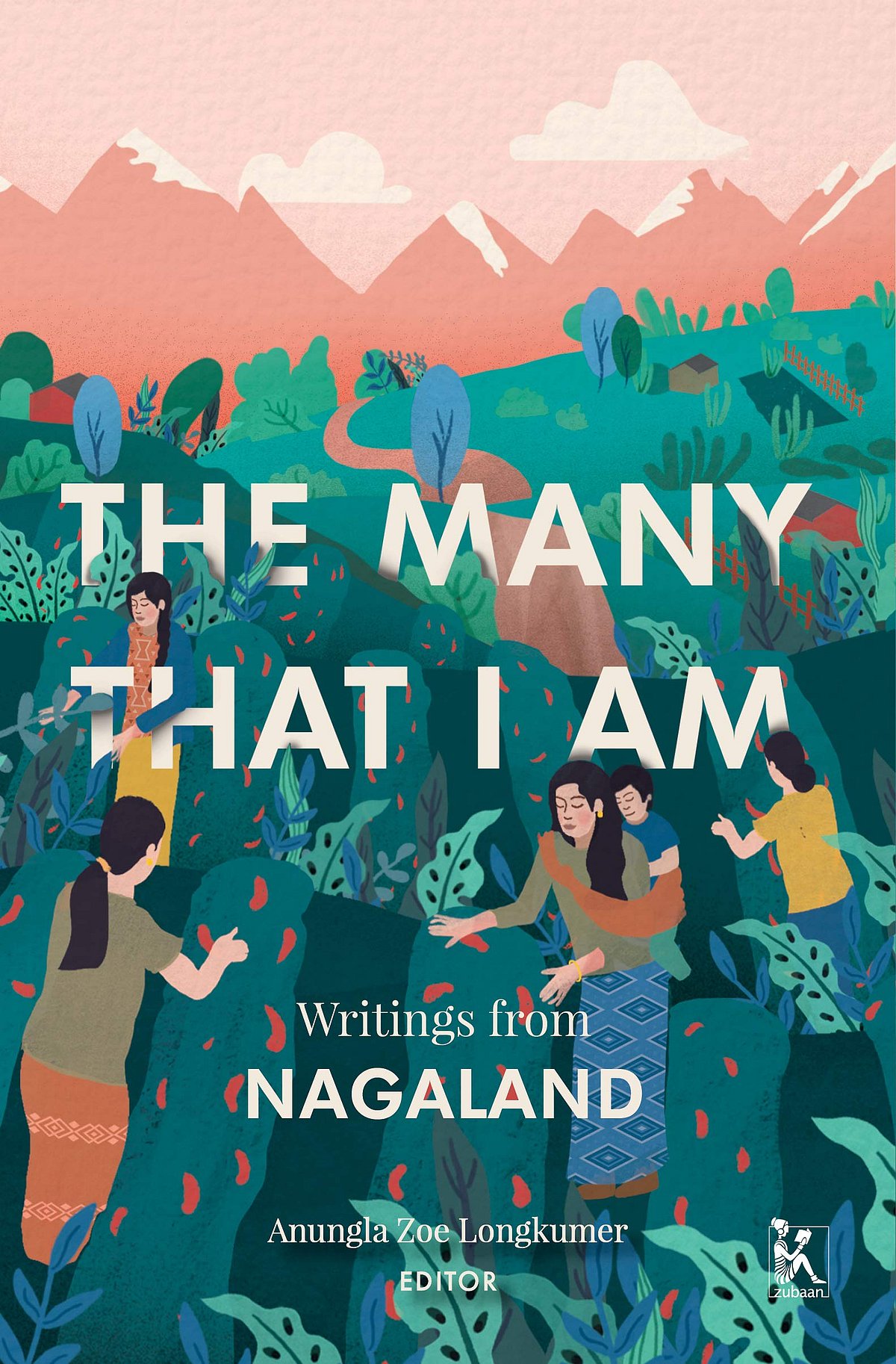

The Many That I Am is a short collection of writings from Nagaland that lives up to its name. It is fresh, multifarious and contains endless possibilities. Edited by writer and filmmaker Anungla Zoe Longkumer, one of the strengths of this book is its ability to recognise the limitation of the written word and not to put it at par with everything that’s unwritten. By now, there are a few popular Naga names that have made it to the literary landscape in English like Temsula Ao, Easterine Kire, Jasmine Patton and others. Longkumer says, “Instead of ‘others’ depicting a somewhat superficial image of the Nagas, it is Naga writers who are now espousing the need for honest probity into our inner selves in order to correct our past mistakes by creating a livable present.”

The honesty reflects most in the artwork and poetry—paintings like ‘Letting go’ (Aniho Chishi) and Marriane Murry’s ‘Untitled’ present this constant tussle between holding on and drifting away. Theyie Keditsu’s succinct poem Odyssey that says, ‘In leaving, you will learn your place’ has similar thoughts to offer. There’s also Thejkhrienuo Yhome’s clever graphic strip A Fairytale Like any Other which reverses the power we associate with the ‘untouched’ and the ‘impenetrable’. A brave female warrior climbs a jagged mountain and shows a tiny cub the way home. The focus here is on the act of climbing—of reaching out and exploration. It is a great metaphor for the entrapment of knowledge and mythology under the hands of few. Experimenting with multiple genres and budding writers could be testing, but this book is a good start.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Crafting the Word, on the other hand is voluminous in its content comprising of 26 writers and a visual artist from neighbouring state, Manipur. Among them, four are Sahitya Akademi winners—Maharaj Kumari Binodini, Sunita Ningombam, Arambam Ongbi Memchoubi and Moirangthem Borkanya—write primarily in Meiteilon (Manipuri), Tangkhul and English. They try to locate the experiences of the Manipuri women across a wide multitude—home and the world, protest, body, desire, silence, widowhood and more. As noted by Nahakpam Aruna, the literary evidence of Meitei-Mayek script goes back to 8th century, while the hill tribes continued to record their stories in the oral tradition. It might be erroneous to think that both these books are sister-anthologies but they do mirror a few commonalities.

The newer writings for example, express abuse from the victim’s perspectives—while Naga writer Neikehienuo Mepfhuo’s story My Mother’s Daughter speaks of the indoctrination of domestic violence through silence, Yuimi Vashum’s poems in Crafting a Word are telling memories of child sexual abuse. Most of these personal narratives are confessional in style and in sync with the oral traditions. The cyclical nature of some issues like daughter-mother generational unease is another thread of intersection between both the anthologies. The women from the older generations try to share the evolution of their ‘wisdom’, the timeline makes this interesting. They try different strategies to convince them of the perks of continuing the order of patriarchy. Sometimes, it is also the way the story is told that the locus of power gets validated in societies that find orthodoxy the only way to ‘preserve’ their heritage.

Women in these contexts are often found to live a complex reality of contradictions—sometimes vocal and at other times silent about the needless loop of the victim becoming the perpetrator of oppression. The worlds we see in these books are very much like our own, to that effect, the prose and poetry have been carefully chosen, and they don’t come across as either nostalgic or euphoric about conservatism. Haripriya Soibam’s terrific translation of Manipuri poems like When the Apsaras Awakened by Chongtham Subadani deserves praise. The rebellion of dancing girls in the original feels retained in English. The flavour and the rhythm of the lines (just like anklets) are bound to strike a chord.

Finally, one ought to read these books not as new ‘literature’ but as new creative forces to keep the conversation going. This is more important than writers from the Northeast being canonised and placed in the academic/market hierarchy of things. The struggle is not simply for visibility but also internal freedoms of many kinds. To quote author Toni Morrison, “Freeing yourself was one thing, claiming ownership of that freed self was another.”