Racing Against Time

IN THE CONTEMPORARY ERA, wealth, fame and power function as popular yardsticks of a person’s success. External forms of validation, such as professional awards, serve as other visible signs of an individual’s achievement. Reinforced by a section of the media, these attributes often mark out individuals who possess them as society’s winners. But these easy, some may argue coarse, parameters do not capture the complexity of human striving and achievement.

In many fields, alternative narratives have encouraged people to look beyond common stereotypes of success, for example, by revealing the hugely unequal nature of initial conditions and persistent socio-economic handicaps or by exploring the lives of those who dared to fail after taking risks at which others balked or after going down a less-trodden path.

What happens when the field in question is organised sport, which unambiguously and unforgivingly defines success as winning, indeed, one in which the whole point of participating is to try and win, even if it is by the equivalent of a hair’s breadth, say one goal in a penalty shootout in football or a fraction of a second in a 100-metre sprint? Is success in organised sport also less straightforward than it appears?

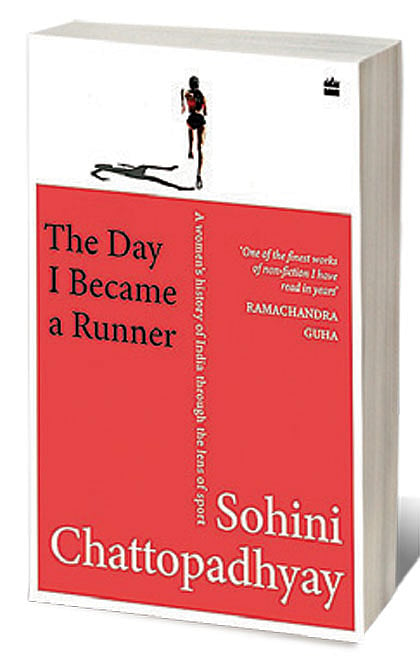

The answer, in The Day I Became a Runner, which includes eight profiles of Indian women runners and one of a grassroots training institution, is an emphatic ‘yes’, even though the author, Sohini Chattopadhyay, does not explicitly say that she is trying to answer this question. It happens organically as she sets out to explore two other key ideas, nationalism and patriarchy, through the women’s stories—an objective encapsulated in the book’s subtitle: A women’s history of India through the lens of sport.

It's A Big Deal!

30 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 56

India and European Union amp up their partnership in a world unsettled by Trump

Perhaps in international sports more than any other sphere, spectators see not only individuals or teams as winning or losing, but also the country they represent. “Sports,” Chattopadhyay quotes George Orwell as famously saying, “is war minus the shooting.” In India, where women have a meagre presence in public spaces and public life, sports, Chattopadhyay writes, gives them “a solid, respectable reason to put…their bodies out there in the world: for national service.” She therefore aims, she says, to delve into what it feels like for women athletes “in a viciously gendered society such as India” to “put themselves…out there” and carry the nation’s hopes.

The book does this exceedingly well and by doing so, infuses nuance and texture into ideas of achievement and success. The book left me profoundly admiring the women athletes, half of whom grew up in very poor families in rural India, for their enormous physical courage and psychological strength. To me, they are world champions all, no matter what their actual tally of international medals.

Chattopadhyay has ordered the profiles chronologically based on the time the women were active as competitive athletes, starting from Independence, barring the exceptional last story about a woman whose sports career began before 1947. In the first three profiles, the author writes about women who all happen to be sprinters: Mary D’Souza, Kamaljit Sandhu and the celebrated PT Usha. In the next three stories, she tells us about athletes who have had to deal with humiliating accusations that they were not legitimate women: Santhi Soundarajan, Pinki Pramanik and Dutee Chand.

Finally, she tells us the stories of Lalita Babar, a marathoner and steeplechaser; the Sunrise Project; and Ila Mitra, an athlete who became an extraordinary and dedicated communist worker. The author ends with a brief epilogue addressing the curious case of the missing Muslim athlete in her account, and looks at other sports at which they have excelled.

The author intertwines the women’s stories with her larger themes, displaying a quality exhibited by many of the book’s athletes, namely excellent balance. She threads the independent profiles together by simultaneously charting how India’s national identity evolved over the years, how its sports culture developed, and how its economy and society changed.

She is a penetrating observer of people and culture. “The gym is the public bath of this i-generation,” she writes. “The coach-athlete relationship has the qualities of romance,” she says. Of a father caught between his feuding wife and sister, she says, he “did what many men in the subcontinent do—stayed quiet and outside his home as much as he could.” Of Lalita Babar, she says, “She was Maharashtrian and had her people’s fabled austere, pragmatic approach to life.”

To tell the women’s stories, Chattopadhyay elegantly weaves together details about their family lives, their social settings, descriptions of how they experienced various key races, their relationships with their coaches, and in the later profiles, media coverage of their careers. Chattopadhyay’s reporting is deep, she has a flair for storytelling, and her prose is fresh and eloquent.

Here is an excerpt from a description of an 800-metre final race that Santhi Soundarajan, a Dalit from Tamil Nadu, ran at the Doha Asian Games in 2006: “The flickers of anxiety in Santhi’s stomach burnt to cinders as she breathed in deeply and swelled her lungs to marshall all the power at her disposal.” The author tells us that Santhi “had come to discover that she enjoyed final-day nerves.”

Chattopadhyay has managed to extract poignant material even from Pinki Pramanik, the most recalcitrant of all the athletes. Talking about how she felt when she began running at night beside the river in her village, Pinki told the author, “I didn’t feel the loneliness that I did otherwise. I had a door of my own that I could open to a place where I could be myself.”

Pinki’s story, along with Santhi’s and Dutee’s, raises the important question surrounding the sex-testing of women athletes. Pinki was accused of rape by a flatmate, while Santhi and Dutee were accused on the field for their “defective sex.” Their stories, says the author, highlight “the central anxiety of being a woman athlete in this moment…Are they female enough? Do their bodies align with the precise measures of hormones, chromosomes and anatomy that World Athletics has laid down for that specific moment…?”

I can’t say that these stories fully clarified the issues for me; they are far too complex. But they did show how insensitively authorities have used the tests and why we need to rethink our approach to the subject. The author describes Santhi’s harrowing and humiliating experience of undergoing this test and of authorities subsequently stripping her of her medal. Fortunately, by the time Dutee came on the scene, she got more support from activists and experts, resulting in her winning her case in the highest court of sport in Switzerland.

Works of narrative non-fiction, like this one, can adopt a complete third-person point of view or include a first-person perspective. Chattopadhyay has chosen the latter. She opens the book by describing her own experience of taking up running as a hobby, and the oddity that she was before the marathon economy became entrenched in India.

But Chattopadhyay does something special: she tells us about aspects of her life that she need not have, sharing some of her own vulnerabilities, just as she does of the women athletes, whom she so empathetically profiles, as if to level the playing field. This is a book about sport, after all, in which fairness is essential to a good contest.

This book makes you look at this country anew. It also made me look at my own life differently, including an aspect involving running. In the fourth grade, my PE teacher, a man who later became one of India’s best athletics coaches, told my parents that I had “springs under my feet” and that if they allowed me to train rigorously he could take me to the national level in sprinting. Until now, I assumed that my middle-class parents did not follow through because they did not have enough money. Now I believe that the reasons were more complicated.