Pulp Friction

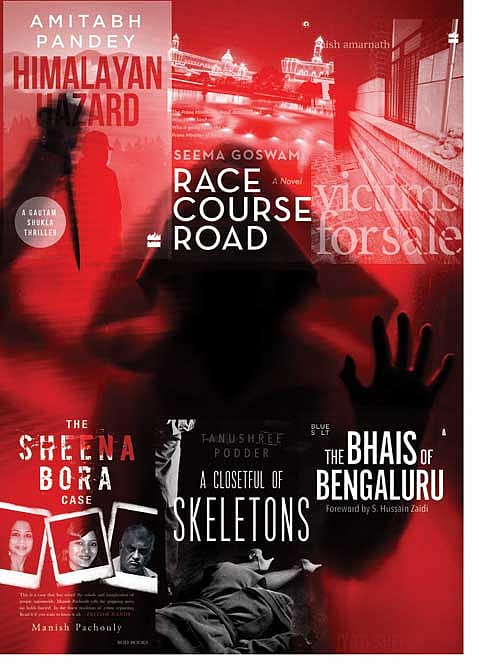

LIKE A DELAYED Christmas present, a boxful of thrillers arrived at my doorstep recently. I found to my delight that half the titles came from Harper Black, the loud and lurid imprint at the otherwise stodgily respectable publishing house HarperCollins, which seems to be upping its market share of pulp. Another book was from Blue Salt, the crime imprint headed by investigative journalist S Hussain Zaidi under the Random-Penguin banner. Then there was one new true crime book from Roli, who seem to be making a foray into the pulp market, and a posh-looking hardback thriller from Aleph. I was heartened to see this spread, considering the scarcity of Indian pulp in English just a few years back.

In Nish Amarnath's Victims for Sale (Harper Black, 317 pages, Rs 299), we follow the misadventures of Sandhya Raman, a former Mumbai TV crime reporter who, after her boyfriend's demise in a terror attack, goes abroad to study in London. Despite having been a hardnosed journalist in India's gangster capital, her overprotective family insists that rather than staying in a hostel where she might pick up bad habits, she lodge with an Indian-origin joint family which is best described as a desi version of the US TV horror-parody of the ideal American household The Addams Family. Within no time, their spooky son relieves Sandhya of her virginity, who, despite noticing that something is rather off, does not pack her bags and escape while there's time, but instead turns quite promiscuous, or as Amarnath puts it in her most empurpled style: 'A strange spiritual coherence deepened my corporal thirst with a vitality I had never imagined before.' During a trainee stint at BBC, she investigates a spurious care home for mentally challenged women where inmates are subjected to unethical medical experimentation and abuse by pimps; coincidentally, the institute turns out to have links to her NRI host family and soon Sandhya's life is in danger. The flaky story is full of fluky discoveries, the action hinges on luck, and implausible situations mar its feeble attempts at realism and relevance. Despite such incongruity and the affected prose, there's something rather delightfully pulpy about the moronic antics of the protagonist and the London that she inhabits.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

Another novel that takes off from Mumbai leads us to the Himalayas, where its action is set: Closetful of Skeletons (Harper Black, 286 pages, Rs 250) by Tanushree Podder explores the murkier sides of Bollywood in a thriller that follows a classic Agatha Christie type plotline. Despite its total disregard of the realism that is expected of modern thrillers, and a thoroughly formulaic construction, one is compelled to read on as an ex-movie starlet about to turn 40, invites all her ex-lovers for a birthday bash in the isolated mountain bungalow where she's hiding from her past. However, she plans to wash her dirty laundry in public in her soon-to-be published autobiography, 'a no-holds-barred account, in which I have revealed everything about my life.' Needless to say, and just like in a typical Christie plot, her fortieth turns out to be her last birthday as she's found butchered in her cot before the weekend is over, while the hard disk on her laptop, on which she had penned her memoir, has been wiped clean. With typical Christiesque gaps in logic and predictable tropes, there is luckily a retired colonel at hand who, whenever he isn't busy playing bridge with his chums at the colonial club, is more than happy to help the constable (who happens to be the ex-starlet's local lover) solve a murder or two. The hill station setting and melodrama add to the novel's old-fashioned feel, and for those who have been missing Agatha Christie's contrived plots, this should come as a boon, though the ending is unsatisfactorily un-Christiean, if you get the drift.

Speaking of ex-colonels holed up in the Himalayas, in Amitabh Pandey's Himalayan Hazard (Harper Black, 269 pages, Rs 299), we reconnect with Colonel (Retd) Gautam Shukla whose adventures in the prequel Himalayan White did entertain despite a certain hasty hackish writing style. In the fresh-off-the-press sequel, Pandey has improved his prose and gets the thriller tone dead right at least in the first half of the book, while he stacks the odds against the hero by weaving together sub-plots that inevitably will converge at some suitably thrilling point.

Settled in a Himalayan village where outsider drug manufacturers start moving in, Gautam takes a break to hang out with former colleagues in Delhi, only to get pulled into Indo-Israeli politics when he along with a young female Israeli security agent, whom Gautam seduces with élan, become witnesses to an assassination in the heart of the capital. The professional hit person is suspected to be a foreign contractor doing freelance work in India, which leads to a diplomatic mess. This places 'wet jobs' expert Gautam and his new lover on different sides of a political barbed wire fence. Written with more adrenaline than regular run- of-the-mill pot-boilers, the narration is engaging enough, despite being somewhat far-fetched in its details, to make for an almost unputdownable read. Sadly, the latter half ends up relying too much on characters reporting their findings to each other rather than showing us how the findings came about—the dreaded 'talking heads syndrome' of narrative art. But even though this isn't a 'spine-chilling thriller' as claimed on the back cover, it's nevertheless entertaining.

Seema Goswami's Race Course Road (Aleph, 285 pages, Rs 599) is a rock-hard political thriller. Although written in an overtly journalistic tone—with a penchant for the kind of acronyms Indian newspapers tend to be littered with and an accompanying lack of literary elegance—one goes along with it. Two of its multiple protagonists are, in fact, primetime TV news show hosts: formerly lovers, now cut-throat rivals. The story construction is refreshingly solid, a complex multi-protagonist chronicle that involves the country's bereaved first family following the prime minister's mysterious assassination during a rally at Delhi's Ramlila Grounds, and the power struggle that ensues between his son and daughter, as well as various other political operators who vie for the national leader's post. Journalist-turned-novelist Goswami obviously has a ringside view from years of political reporting, so the insights into the intrigues that surround statecraft, down to the pettiest scandal-mongering, appear incredibly realistic, and although a concoction, it is a potent decoction that should make Race Course Road a sure-fire bestseller and mandatory must-read, what with elections coming up and all.

Even closer to reality is The Sheena Bora Case, (Roli, 230 pages, Rs 395) a factual retelling of the infamous murder that shook India a few years ago with its sensational cocktail of Mumbai high- society sleaze. For those who have been in a decade-long coma, it's essentially the tale of a morbid 'first lady of Indian television' (as she was called), who initially abandons her firstborn child, Sheena, and then murders her in cold blood once the daughter is about to enjoy life as an adult. All because of trivial money issues. Investigative journalist Manish Pachouly's report is a reasonable compilation of data for those who want to give the facts of the gory story a once-over, including the gruesome details of how the homicidal celeb mummy disposed of her daughter's corpse with the help of one of her multiple ex-husbands, as well as the trauma inflicted on Sheena's siblings: the biological brother whom the murderous mum gets committed to a mental asylum before trying to kill him (but who, unlike his sister, senses something fishy and manages to escape two attempts), her half-sister (used as an occasional pawn in the game, but otherwise curiously absent in the book), and Sheena's stepbrother- cum-lover (who nearly loses his mind after the murder). Unfortunately, the narration depends too much on secondary sources, as if the writer has been sitting at home googling, cutting and pasting, rather than doing the necessary legwork. Furthermore, parts of the book overlap and repeat each other, dull emails are quoted extensively, while over 80 pages of the slim volume consists of phone transcripts downloaded from India Today's webpage—phone calls during which Sheena's live-in-boyfriend-slash- killer-mum's-stepson discusses the case with his parents. The reader has to act as an editor and search for the pertinent dialogue in the unedited mass of text. Although the presentation is admirably matter-of-fact and lacks any overtures at dramatising, it lends itself to a slightly un-engaging reading experience akin to browsing Wikipedia entries.

A by far racier true-crime paperback is The Bhais of Bengaluru (Blue Salt, 226 pages, Rs 299) by Jyoti Shelar, journalist and protégé of the legendary S Hussain Zaidi. In just about 200 pages, Shelar narrates, in a daringly epic sweep, the history of rowdy-sheeters and their gangsterism in Bengaluru, from its mid-20th century origins which she traces to the city's wrestling clubs from where strong- armed ruffians branched out from noble sportsmanship to minor extortion of protection money. The book trails an interesting development from relatively amateurish rowdyism back in the day, fuelled by political nexuses, to semi- professional organised crime syndicates moving into legitimate businesses such as the booming real estate under the leadership of 'reformed' name-and-fame dons. The writing is graphic, with goons beating each other to death in full view of bystanders. Someone swirls someone else's 'body in the air, banging his head on a huge rock. Blood splattered on his face but Koli Faiyaz remained unfazed. Naem died a death that was typical of poultry in Shivajinagar's butcher shops: brutal and ghastly.' Essentially, one could call this an alternative underground history of Silicon City.

So I'd say we do have a decent harvest this spring with plenty of time-pass to pick from. My main complaint about these titles is that most publishers haven't edited them for style or grammar. A little polishing could have gone a long way in removing irritating errors, though one also wishes that the writers themselves took a serious approach and cared for their writing enough to reread and rework, rather than sending their first drafts to print. It is true that American pulp writers, especially in the heyday of the industry, rarely took a second look before submitting stories hours away from deadline, but on the other hand many of them were expert craftsmen—seasoned by years of rejection slips. And if they got it wrong, they did it with such panache that readers seldom noticed.

Here, on the other hand, an overuse of the thesaurus threatens to ruin the reading experience. In the first few pages of Victims for Sale, to take a glaring example, instead of using simple words like 'said' and 'asked' and 'shouted', the author slaps in 'croaked', 'rang out', 'exclaimed', 'sighed', 'commented', 'ventured', 'mumbled', 'suggested', and this comes combined with a bombardment of 'padded', 'stepped', 'edged', 'dashed', 'trudged' and 'waltzed' when a straightforward 'walked' or 'went', or at the most 'ran', would do a more efficient job. I should point out that per se there's nothing wrong with a fancy vocabulary, but it should be reserved for one's Shakespeare pastiches and kept out of thriller fiction. A deluge of posh words as listed here, when one opens a book can be especially off-putting for readers looking for a fast-paced narrative.

Another problem that aspiring thriller writers tend to have is an inability to trust their audience's intellectual faculties. Ideally, information should be embedded discreetly within the prose, not hammered into a reader's skull like nails into a coffin. In an inconsequential passage in A Closetful of Skeletons, four sentences are used to convey something so minor that it ought to have been contained in a subordinate clause of a sentence: 'The pulsating rhythm of Caribbean music hit his ears as he walked into the hall. Arif smirked as he remembered Ramola's large collection of Jamaican and Caribbean music. It was obvious that she was in charge of music for the evening. Whatever else might have changed, her taste in music surely hadn't.' This lack of economy in language slows the pace to a snail's crawl.

So instead of allowing readers to draw their own conclusions, often times these novels are full of information, frequently re-stated in an only vaguely different form (as above), or, even worse, the dialogue will be made to carry the burden of unwieldy info dumps. Sample this unnatural exchange from Himalayan Hazard in which a rustic servant informs the hero about a location where no actual action takes place (even though the plot hinges on its existence):

'Arre, sir, have I told you about Tinauli village?'

'No, Joshiji, you haven't told me anything about Tinauli. Isn't it on the opposite ridge across the valley?'

'Yes, over the top and down the other side, a little… The young people have all left and the old ones are dying off rapidly.'

'Another hill village disappearing off the map, eh?'

'Ah no, sir, that is the amazing thing. But let me tell you the story from the beginning…' And on it goes, as the servant is made to voice a colossal load of data in the guise of an amicable evening chat.

Having said that, I look forward to seeing what happens in the domestic pulp crime industry within, say, another year when the genre matures further and by which time standards ought to get higher. Although the quality is uneven among the titles reviewed, I'd say that it is on an average twice as high as last year's crop. Things are pointing in the right direction, and, judging from these books, the future star of Indian thriller fiction might be a woman.