Prisoner of the Present

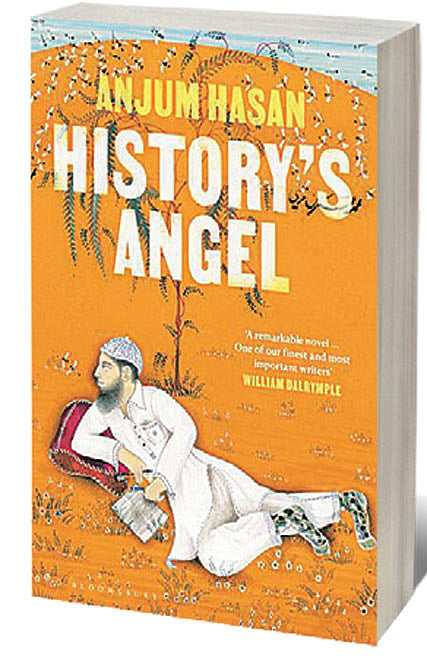

IN ANJUM HASAN’S History’s Angel (Bloomsbury; 288 pages; ₹799) the protagonist Alif is many things. An idealistic history teacher, a besotted Delhi resident, and yes, also a Muslim in contemporary India. “What if there were someone who may on the face of it be classic victim material but doesn’t see himself that way and just wants to be left alone?” says Hasan in an email interview, reflecting on the spark behind her fourth, and latest, novel.

Is it possible to be an apolitical Muslim in contemporary Delhi? Alif is a tragic hero of sorts; dreamy, often naive, not very observant as a Muslim. He avoids confrontations, delights in taking his students on field trips to Delhi’s monuments, and exults in the past. Unlike Tahira, his more ambitious, career-minded wife he is reasonably satisfied with his lot. In terms of action, not that much happens in this novel, although there is one incident that sets events into motion.

During an outing with his nine-year old students to Humayun’s Tomb, a student called Ankit badgers Alif. He wants to see a Hanuman temple instead. During the trip, the boy goes missing in the complex. It turns out to be a deliberate act of truancy. On being found, he asks Alif: “Are you a dirty Musalla?” The mimicry of an adult slur comes as a sudden sting. Piqued in that moment, Alif twists the boy’s ear. This sets off a disciplinary enquiry and Alif’s suspension. The incident takes place in a world where Muslims are being lynched and a new discriminatory citizenship bill is on the anvil.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Hasan, who’s first published work was a book of poetry in 2006, has also written short stories, literary criticism and three previous novels. But Alif’s story was always going to be a novel.

“This monstrous reality I’m writing about here, the political situation, felt like it needed the breathing space a novel offers, through a character who gets entangled in it without wanting to,” she says.

Being Muslim places him in a precarious position, even if that’s not something he dwells on. At one point he is cavalier about the proposed new laws. “(T)here are more than two hundred million of us… Are you crazy? How many detention centres would that need?” This menacing new policy is one of several glancing references to real world politics in the novel.

“I didn’t set out to write a novel with politics, though I think there is one implicit,” says Hasan. There are throwaway references to shouting television anchors leading charged debates on prime time. Teachers at school lapse into WhatsApp-style versions of history about the big bad Muslim invaders. Casual Islamophobia is everywhere: whether it is a taunting student, a physical attack or the everyday humiliation of house hunting.

“All my novels seem to be driven by an anxiety about the zeitgeist and have characters who are in one way or another undone by it,” says Hasan, on whether this is her work closest to the present. “The question is how much space does public life leave for private life? And how to use private life to reflect on public life? In the earlier novels perhaps there was more space, but by setting this one in today’s North India I’m putting a greater squeeze on the characters.”

HASAN’S FIRST NOVEL, Lunatic in my Head (2007), had three intersecting storylines and was set in the 1990s in her hometown Shillong. Neti, Neti; Not This, Not That (2009), which was longlisted for the Man Asian Literary Prize and Hindu Best Fiction Award, followed a young woman who moved from Shillong to Bengaluru. It was described as the ultimate Bangalore novel, for the way in which it explored a newly vibrant city, bustling with migrants, nightlife and opportunities. With The Cosmopolitans (2015), Hasan followed a 53-year-old single woman while dipping in and out of the art world. Those characters were less encumbered by the pressures that Alif and his circle face.

Alif himself doesn’t embrace victimhood, as Hasan says, but retreats into other worlds: Iqbal and Faiz, Ghalib and the Sufis, Nietzsche, Nehru and Napoleon. Hasan is in deep conversation with “the past, literature, art, poetry, as a way of balancing the pressures of the present if not getting the hell out of it,” she says. When asked if fiction writers have a role today, she demurs. “It’s a marginal one. The politics is so virulent that the writer retreats into a quiet role—sticking with self-effacing or at least low-key characters, trying to rescue inner life.”

The novel is constantly toggling between the two. The musings and inner world of Alif in stark contrast to the ugliness of the world outside; sectarian strife, second-class citizenship, extractive capitalism, the creeping hold of fundamentalisms both Hindutva and Islamic. The novel “seems to be the only form that can give shape to that unstoppable stream of consciousness,” according to Hasan.

When a novel is so rooted in the now, is there not a danger of the material being too close to the news, or the danger of being didactic in tone? “There’s definitely that danger and I’m all admiration for writers who can be extraordinarily subliminal about the dark times they’re describing, like Chris Isherwood in Goodbye to Berlin or JM Coetzee in Disgrace, or Michael Ondaatje in Anil’s Ghost. In India, politics is a staple of everyday conversation, though, so that had to come in but the attempt was to show the main character, Alif, as trying to keep away from present-day politics and from ready opinions about it.”

Would that then make this a “novel of ideas”, as one of her previous novels was described? “I can’t think of a great novel that is not playing with ideas,” says Hasan. “Of course, some writers have their characters discussing ideas upfront and at great length like Turgenev and Dostoevsky and in others the ideas are concealed as metaphors like Kafka.”

The title itself is a reference to Walter Benjamin’s essay which in turn refers to a figure in a Paul Klee painting. “This is a very Hegelian view of history—inexorable progress, the impossibility of going back to the past, the appeal of a promised future. Benjamin takes the Marxist view, he says what we want is remembering not for nostalgia or scholarship but as an impetus to revolutionary action. I thought it would be interesting to apply that to a character who feels himself a prisoner of the present. Even though he is unlikely to revolt.”

Benjamin is one of several philosophers and thinkers who shows up in the novel either obliquely or in direct references. Hasan herself studied philosophy in college. “I liked philosophy as a student though it could have just been a romantic attachment to ideas, the cultivation of the serious air, because something about that felt poetic,” she says. “In fact, I started writing poetry and studying philosophy at the same time.”

Like her previous work, there is a strain of dry, dark humour that surfaces, even in the grimness. In one caustic moment Tahira says in exasperation: “Is that all we are?.. Bawarchis? Poetry-spouting fools with minced mutton coming out of our ears, thinking only of Allah and pining only for behesht between mouthfuls of zafrani pulao?”

HASAN’S PREVIOUS TWO novels were set in Bengaluru, where she now lives. History’s Angel is a true Delhi novel, and could have been set nowhere else. There’s the shimmery, new-age Delhi that emerges in the malls and flashy capitalist enterprises that Tahira so hopes to work for. Then there is a grottier underbelly of “sooty squalor and haphazard hustle”. And of course, the city as a grand, monumental capital. “I’ve always had a thing for Delhi’s past,” says Hasan. “I was never based there, just been a regular visitor, but it was once my parent’s city so it’s both familiar and strange. I think it’s a yearning for Delhi that got channelled into Alif’s character, the figure who has never left town, who hates the idea of travelling while feeling also a tolerant, intimate hatred for his home-city or at least some sides of it.”

For Hasan, who dabbles in a variety of forms, each has its own charms. “I can get absorbed in each in their separate ways and seem to be swinging back to each sequentially,” she says, “though I think the criticism has always gone along with whatever else I’m doing because I need to read other writers, read my contemporaries, even when I’m writing. And then I can’t resist analysing the present moment through those books.”

She describes her literary influences as both “wide” and “wild”. “I read a lot of fiction—more Indian than Western, though growing up it was the opposite. Every year at least a couple of instances of new Indian writing will make me sit up.” Recent books include Sara Rai’s Raw Umber, I Allan Sealy’s Asoca, Geetanjali Shree’s Tomb of Sand, Chandan Pandey’s Legal Fiction, Ashutosh Bhardwaj’s Death Script, and Ankush Saikia’s Forest Beneath the Mountain. More recently she has been drawn to Chinese fiction in translation, as well as English writing by expat Chinese writers, “which has been a revelation simply for its seeming closeness to the people”.

History’s Angel is set in a middle-class milieu. Its characters move between English, Hindi, Urdu, Punjabi. Which takes us back to the original problem of the Indian writer in English: How do you write an English novel when the characters themselves are thinking and working in different languages? What are the challenges or factors that you have to be cognisant of?

“It’s an old question and not one that any of us Englishwallahs have come up with a good answer for,” says Hasan. “People talk in Indian languages and we write them in English.” Hasan is married to the writer Zac O’Yeah. “We influence each other greatly but have managed so far to remain different people,” she says, on the literary dynamic in their marriage. “Our styles differ but our interests are greatly entangled. And we are each other’s first readers, which has been critical for me because he has a very good head for both fact and fiction.”

For her next piece of work Hasan returns to Shillong. It’s a piece of non-fiction she has been working on for the past few years. “It’s an attempt at a people’s history,” she says, “of this fascinatingly mixed and modern town, the story held together with my own memories and experiences of it.”