Passion Plays

THE PRESENCE OF death looms large in this voice-driven collection of thorny love stories, written under the pseudonym, Ekarat. Ekarat, the author bio tells us, ‘is an alter ego with a million stories to tell.’ It appears that a Banksy-like author has debuted in the world of Indian short fiction.

The narrator of the first story reveals more about Ekarat: ‘I am a humble editor of a travel magazine and a struggling writer after dusk. I live in a neat bachelor pad in south Delhi, with a terrace built for evening dos, and I have the most awesome housemaid in the world. Two dogs, Blackie and Joey, guard the gate of my house. Sex is plentiful.’ Keep in mind though, that this is a book of fiction.

In these gripping tales, love turns cold, love turns sour, love kills, and yet Ekarat, or rather his characters, continue to believe in the redemptive power of an emotion, which provides fodder for a million pop songs. Indeed, love also blooms. The stories come tinged with pop song corniness, and in a good way. The story titles are like names of songs: ‘Perizaad’s Lover’, ‘Love Has Come to Town, ‘Baby Did a Bad Bad Thing.’

Not a trace of cynicism and yet darkness lurks at every corner; the pursuit of love is an essential part of self-knowledge and self-discovery; the road forward lies not in sitting in paralytic judgement over others but in the acts of forgiving and accepting, or simply moving on.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Ekarat takes as his starting point a truth that is contested in contemporary times, that human beings are flawed and messy creatures, especially in love: ‘By accepting her past, what great favours had I done her. And who the hell was I to accept her? I had merely been a bystander in her narrative. She had built and broken her life, and built it again.’

In the stories here, the terminally-ill owner of an FM radio station tries to find a lover from his past; a famous editor falls in love with a junior colleague; two seven-year-olds bicker over a marriage proposal; two 12-year-olds, trying out a kiss for the first time, get their braces entangled; an army cantonment romance falls prey to the Hindu-Muslim divide; an Indian student in Brussels strikes up an unlikely virtual friendship with an Indian girl in America: ‘Then I find out that she’s not just pro-American but right-wing, which I have a very hard time connecting with.’

In a story inspired by Robert Browning’s Porphyria’s Lover, adulterous Perizaad doesn’t protest when her lover ‘tied her hair around her neck and gently pulled’ with murderous intent. She gently encourages him instead: ‘“Please... do it,” she completed her death sentence.’

The stories have a strong sense of place. Delhi is as much of a protagonist, from Amar Colony digs, a flat in Munirka DDA, a Saket coffee shop, an unknown Gurgaon bar, to a Chattarpur farmhouse, a Jorbagh bungalow and the India Habitat Centre.

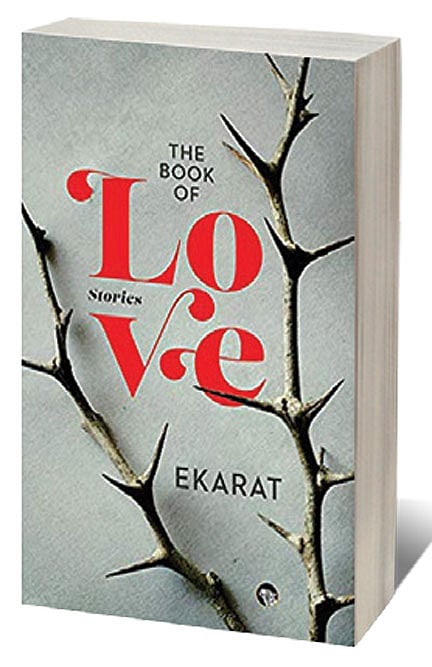

The Book of Love is a triumph of straight-on infectious storytelling— the writing is low on description, shorn of metaphor and literary pretension. It signals the arrival of a bold new voice, an outsider artist banging on the closed doors of Indian writing in English.

The quick fire dialogue draws the reader in. There is a relentless raging momentum in even the shortest of stories; the reader is carried along in its sweeping arc. Ekarat’s narrative fluency though at times suffers from a breathlessness that could have benefited from editorial temperance. Resorting to cliché, then calling out oneself for doing so, does not absolve the author of the crime of using the cliché in the first place: ‘It might seem like a cliché that Europe would be a vacation and Africa a punishment...’ and later, ‘he’d lost weight, had a shaggy beard and smelled like a sewer. He was a walking, fumbling cliché of a wreckage.’