On the Run

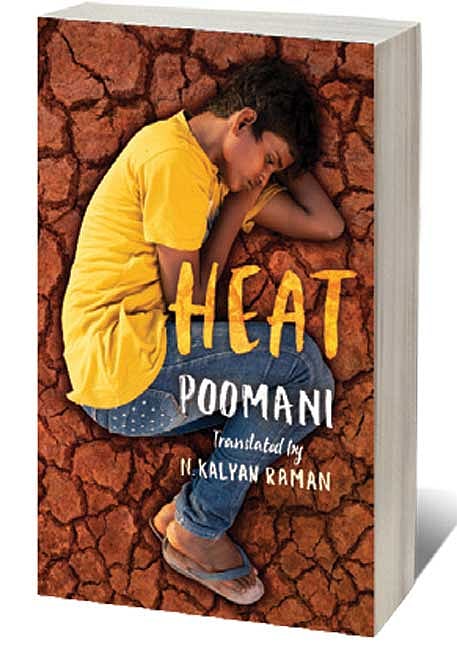

BEATIFIC CALM PERMEATES large expanses of the renowned Tamil writer Poomani’s novel Heat, the first of his works in English: ‘The silence pervading the air was disrupted now and then by the roar of the wind blowing through the hills. Birds plunged swiftly into the dark and disappeared’; ‘He watched the ever smaller ripples rise and fade in the watery expanse of the irrigation tank.’ Equally tangible is its visceral understanding of violence and how casually it is assimilated; day-to-day survival is successfully juxtaposed with the larger sense of urgency that pulsates terrifyingly through this classic tale of oppression. First published by the Sahitya Akademi award-winner as Vekkai in 1982 and soon to be a film, Asuran by filmmaker Vetrimaaran, Heat, in this incarnation, is an uneven yet moving account, based on a true story; where a poor, lower-caste boy kills a powerful landowner to avenge his brother’s murder and goes into hiding with his father.

Father and son spend a slow, suspenseful week in the wild, which provides the frame of the novel. Seeped in flashbacks of domestic life, the novel also revels in their life on the run. The men sleep in graveyards and cane fields, encounter possessed wanderers and wise toddy-tappers, and navigate great dangers and small taboos with tragicomic serendipity. For, 15-year-old Chidambaram is both unlikely hero—the younger brother who usurps his rogue father, Ayya, as avenger of his brother Annan’s death at the hands of villainous Vadakkuraan—and merry, William-like outlaw, scampering up palm trees and unearthing abandoned cooking vessels. ‘Is it bravery only if we fight face-to-face?’ he asks his father indignantly, when Ayya reminds him that they had to hide and kill Vadakkuraan.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Ayya and Chidambaram discuss the life they left behind and the one they must lead with both droll machismo and plaintive sorrow. For, the impasse is deep and unavoidable; Annan has been cruelly cut down by the same forces which threaten their livelihood, and obstruct them at every pass. ‘Shouldn’t there be a limit to the atrocities these big men commit?’ asks Chidambaram’s charismatic uncle Mama, at one point. And Ayya tells his son of when he stood up to the oppressors as a young man, fighting the resulting case and serving nine years in prison. He struck a blow for the larger cause—and retrieved his land, even if it now lies fallow. Small victories, after lengthy battles.

As Ayya admits, nothing can console them for the loss of Annan. Yet, their family, bound together by a simple yet potent love, must somehow find new purpose in the joint survival whose value is constantly weighed up by each character—and the women, importantly, will keep love and conflict ablaze, pampering their men adoringly even as they swear to drink the blood of their enemies.

They are also charged with the strength of those who live close to the earth. Luscious paeans to nature’s bounty and gorgeous accounts of honey- gathering, like in Perumal Murugan’s wonderful Seasons of the Palm, bring the world of Heat to vivid life, together with descriptions of villupattu—storytelling through traditional folk songs—injustice and animal sacrifice, bringing to mind the world of Chinua Achebe. But it reaches us as a series of stills, here. The dialogue is feisty, but at times wooden; its choppiness is charming but does not quite translate. One-liners cascade into ripostes and the men’s bravado parodies itself, but the effect is sometimes dry, even stilted. Similarly, there are some abrupt transitions at pivotal moments, which mar their effect.

Still, how can we ignore the bounties within our reach? Chidambaram finds one of his finest resting places in the roots overhanging a temple, before considering surrender: ‘When he lay down, the sky stretched above him as if he was astride a flying horse.’ At a time of turmoil, he is able to find peace and beauty, to still his impatience, to remind us of the resilience of youth and, even, the ephemeral.