On the Beach

AT ONE POINT halfway through Sabin Iqbal’s The Cliffhangers, Moosa the protagonist finds that a black spider was eerily ‘staring’ at him while he was busy kissing Tahira, his lover. Moosa describes it thus: ‘I kept an eye on that ugly, spooky spider, afraid that it might metamorphose into a giant man-eater.’ Few pages before this incident, he shudders at his incestuous sexual act, prompted by a cat which ‘looked on’ and what would happen should it ‘speak out’. He also compares himself with a squirrel who ‘witnesses’ his semi-clothed bathing sister-in-law by mistake. A reader is hooked to the tension of private-public gaze, of interrupted climaxes, in this story, which also partially reminds one of Derrida’s naked cat in The Animal That Therefore I Am.

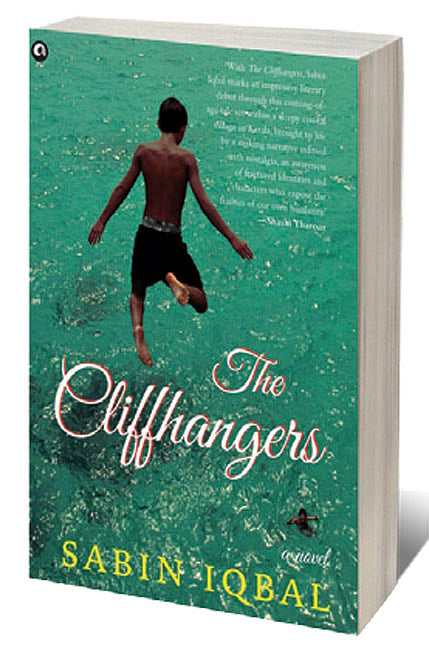

The operation of gaze and consciousness might seem rudimentary, but in The Cliffhangers, it is crucial in telling a bittersweet tale of four young men (Jahangir, Usman, Moosa, Thaha) by the Varkala beach in Kerala, who are infamous for their erstwhile mischievous antics, cricket games and sexual perversion. Especially because the village they share is ‘talking’ about the rape of a foreign tourist and these men happen to be the prime suspects. Iqbal’s plot is easily identifiable and feels like a film—the momentum of interlaced metaphors and humour makes one all the more curious and excited. His narrator Moosa is impeccable with descriptions—mainly when he is describing flaws. Be it his family or tourists at the beach, torn religious camps, the village immigrants to the Gulf or the police.

It's A Big Deal!

30 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 56

India and European Union amp up their partnership in a world unsettled by Trump

As with much of the country’s affairs at present, the police determine the fate of society—including the boys who loiter on the beach. This ‘system’ is closely knit with the divisive (and violent) ideological poles—green, red and saffron. Moosa says, SI Devan is a ‘dickhead in police uniform’, ‘a rattlesnake that can spoil your dinner’. But their greatest weakness is that they paint all foreign tourists with the same brush. Iqbal is clear from the beginning that this leads to dead ends as something deeper runs in the social constitution of Varkala. ‘In a way, we are sandwiched between two Christian communities of contrasting lifestyles—one is poor and crass, and the other, Anglophiles and rich—and two redundant lighthouses punctuating our village like exclamation marks.’

Yet, as the lives of the four men revolve around powerful institutions with ulterior motives, it is their unrealistic aspirations that appeal to us. The fact that they find local methods of rebellion in spite of the pressures to succumb to what youths are ‘supposed’ to do/read/eat/drink makes a compelling point. The hilarious necessity of the tourist season, for instance, which they eagerly wait for, only ‘to speak in English’. Then, they get entangled in petty fiascos owing to their names—they are easily targeted and that places them at the brink of the cliff. But dismantling the spectacular ‘view’ from the cliff is also what Iqbal does—perhaps to stress the vulnerability of these men and the changing contours of sociopolitical governance around

the beach.

Undoubtedly, this is an engaging story, though in the animal/tree imageries the author goes slightly overboard. Then, as the links to the current party and beef politics pace up following a murder, the prose falls, like beach sand, from the reader’s grip. Nonetheless, Iqbal’s book, by stepping into very sensitive topics has directed the reader to look beyond that clichéd cliffhanger shot of films we’ve grown up watching. The present is where one’s ‘name is the enemy’ but the precipice is where we could probably fight that idea. Hope, however suspended, is serious business. That’s how most cliffhangers leave us anyway: longing for more.