Mum Is the Word

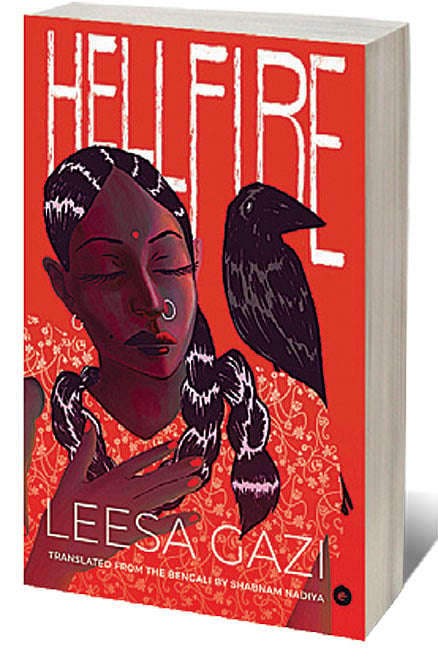

BY UTTER CHANCE, Lovely is allowed to leave home alone for the first time on her 40th birthday. ‘If, in their lives, a different kind of day appeared, it was like a meteor, manifesting and disappearing,’ she ponders, while a choice stands before her. Leesa Gazi’s stunning novel Hellfire unfolds over this day of unprecedented possibilities.

Lovely and Beauty, younger by three years, are held under permanent house arrest by their mother, Farida Khanam. It is a house arrest in which elaborate meals are served, birthdays celebrated, lengthy beautification rituals performed, and television viewing is encouraged. The sisters are allowed to go out together sometimes, or with their mother. It’s only around fifty pages into the book that one realises that Farida is not a widow; her feeble husband is around but often out of sight and mind, carefully stepping out of her way.

The powerfully narcissistic Farida is brilliantly etched by Gazi. This is a mother who first forced her family to move houses because her children had gone to the roof unsupervised, then pulls them out of school for a year when the principal reprimands her for being paranoid, eventually choosing a school that she can watch from her balcony. She ultimately ensures that her adult daughters have no foothold in the world which is not directly under her thumb. She has an unshakeable belief in her goodness as a mother, coupled with a sense of injury: ‘Nobody understood she was saving her girls.’

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

As for the daughters themselves: they are complex beings, largely driven by subconscious feelings, gaslit within an inch of their lives yet lulled into comfort. Lovely has prayer, and a man in her head whose voice keeps her company. Beauty has obsessive pampering routines. Both have their contraband pleasures that make life easier. Somewhere deep down, they know their family is unhealthy. Lovely, considering what might happen if she misses her curfew, imagines: ‘[She] would get the whole story out of her, bit by bit, like a grater scraping the flesh from a coconut. Then, in the dead of night, Amma would just give her a little tap on the back of her head with a pestle. Game over.’ Beauty knows this too—when Farida had discovered Lovely’s dalliance with a cousin, it was Beauty who was threatened: ‘You don’t know me—

I’ll just finish you off.’

Expertly paced, the novel is structured so that at a crucial point in Lovely’s day, the perspective shifts instead to Farida’s household as they wait for Lovely’s return. Farida is an accurate portrayal of one way in which abusive women express their internalised misogyny. Her own helplessness, perceived or otherwise, within a larger societal framework works to an advantage. Farida exerts perfect control over her household through the ruse that she is protecting them from the evils of the world. ‘Nothing took priority over their needs and safety… She hadn’t even married them off. Her anxiety over what kind of life lay in store for them after marriage hadn’t allowed [this].’ This is only one among her ruses; the household pivots on a secret from her past.

In its terrifying realness, Hellfire offers a convincing counterpoint to trigger warnings in art. “It sounds a bit heavy,” a close friend said while I was reading it, gently omitting the “for you”. I did not see myself in this book, because I am neither Lovely nor Beauty. But I know their mother very, very well. Indeed, there is nothing caricaturish about this novel that absorbingly depicts what life within toxic families can be like. How could a novel that reflects the most profound source of my wounding have left me feeling uplifted for days afterwards? Uplifted, and fortified perhaps by the knowledge that one’s darknesses are not unique in the world. Gazi’s extraordinary novel does just this: raises the shadows to the light, thereby setting something free.