Medical and Social Drama

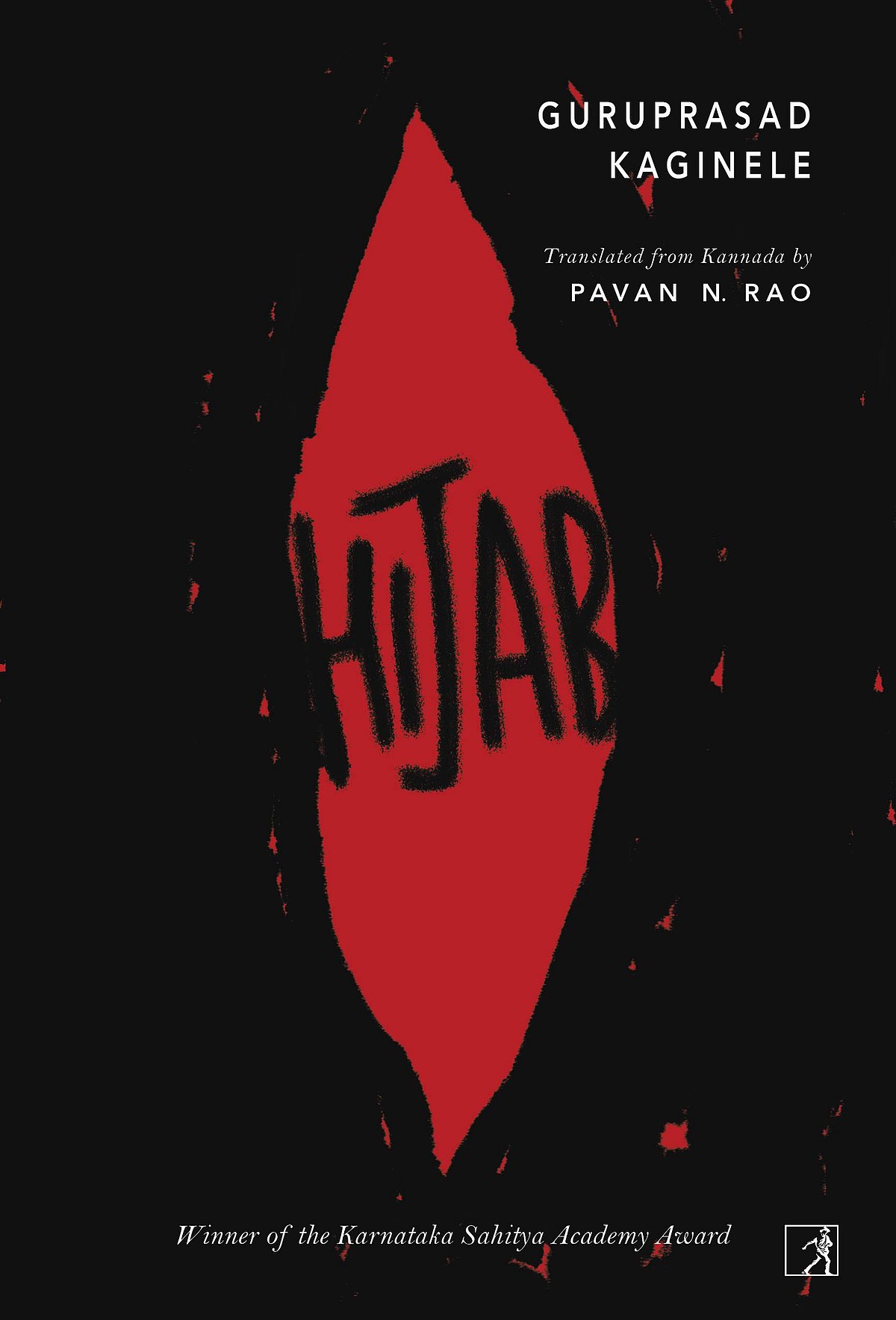

It’s a truth universally acknowledged that the novel in translation in India is bolder in its themes and gutsier in its form, often trumping original works of Indian literature in English. The fire was ostensibly lit in recent years by its poster children— Benyamin with Goat Days, Perumal Murugan with One-part Woman and KR Meera’s Hangwoman. Guruprasad Kaginele’s Hijab is poised to join that list since it turns the spotlight on unique themes of identity politics, racial prejudices and cultural differences among immigrants through the lens of an Indian immigrant doctor.

Translated from Kannada by Pavan Rao, Hijab represents the fast maturing phase of the Indian immigrant experience in novels. Kaginele does this by using the Indian experience in America as a trope to expand the novel’s scope to include migrants from other communities.

Hijab’s characters are doctors from Karnataka, Guru (the titular character shares his name with the author), Radhika and Srikantha, who’re serving their mandatory five years on J1 visas in a fictional town in the ‘American heartland’ called Amoka (if you think the name heavily resembles a Kannada word, you’re not alone). Successful completion of five years of medical service in rural America ensures a green card and a pathway to an American citizenship and future prosperity. But the lives of Indian doctors in an all-white town is not without its challenges—racial and cultural alike.

The town has recently had an influx of immigrants from Africa, a group collectively referred to as Sanghaali immigrants. Citing religious grounds, Sanghaali women refuse C-sections when admitted to the Amoka hospital even as they face complications. When doctor Radhika operates on a Sanghaali woman to save the mother and the baby, it sets off a series of unfortunate events.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

A media spectacle ensues even as the question lingers whether these strange beliefs enforced by religion are solely restricted to the Sanghaali’s. As the book builds on the perplexing stand of Sanghaali women’s refusal to C-sections, it introduces an equally jarring catholic ritual where an American family cuts open a dead 16-week-old fetus from their daughter’s womb—as opposed to the common practice of DNC—so the fetus can be offered a proper burial, enabling its easy passage to heaven.

Why is one religious practice more tolerable than the other? Why is religious tolerance restricted to the racial majority of the host country? By forcing the reader to introspect on these questions and perhaps check their subtle biases whilst at it, the novel accomplishes a remarkable philosophical depth. By striking a balance in its portrayal of its characters, Hijab makes them immensely relatable.

In its translation, Rao’s fluid prose deftly captures the underlying social conditioning and the resulting patriarchy an adult Indian man carries within himself despite exposure to sophisticated and educational environments. Guru is also often conflicted and forced to self-reflect on his subtle race and cultural biases towards other brown people.

In a nutshell, Hijab is a medical drama that dips its toes into social justice, religious fastidiousness even the cost of medical care, racial discrimination and presents the immigrant experience from a rare angle. This fascinating mix of themes and ideas make the novel an immensely rewarding experience. The novel portrays the realities of not only Guru and his team of doctors but also the other immigrant groups and how lives alter when they get tangled in the cross wires of systemic racism in America.

Additional themes are rife too—on integration into the American society, the novel highlights how, despite living in America, immigrant life is either lonely or confined to indigenous pools of ecosystems. Guru muses: ‘I lived in a bubble. Not once had I ever gone to a co-worker’s house..... Beyond an odd comment about family, pastime and politics, our social life in America is dotted by our own rituals, ... Our awareness of Amoka is limited to the outer layer of its outer skin.’

Kaginele, an immigrant doctor himself, has seven Kannada books to his credit and Hijab published in 2017 went on to win the Kannada Sahitya Academy award. As a powerful fable on racial prejudices and immigrant identity tied with the ethics of the medical practice, it won’t be a surprise if Hijab continues its award run at the literary festivals in its English translation.