Loyalty and Longing

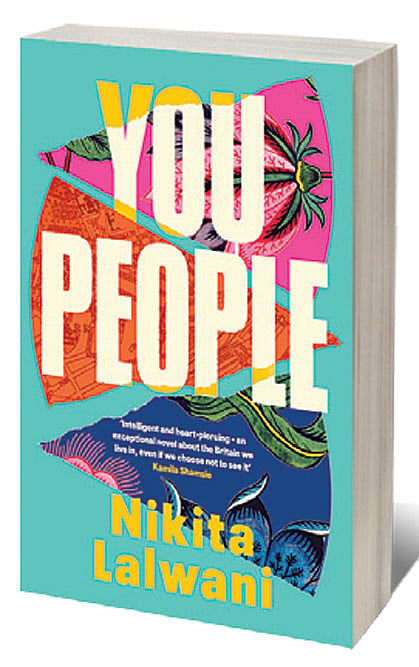

‘IT’S NOT WORK that makes us leave home and come here. It’s love. Love for our families.’ That fierce assertion by an immigrant to the UK in Sunjeev Sahota’s powerful The Year of the Runaways is what comes to mind when reading Nikita Lalwani’s third novel. In You People, which is also about migrants in Britain, Lalwani perceptively traverses the terrain of loyalty, loss and longing.

It’s largely set in the grand-sounding Pizzeria Vesuvio, a small restaurant in a part of southwest London that’s ripe for gentrification. Despite the name, the restaurant is owned by Tuli, a Tamil from Singapore, while the kitchen is staffed by Sri Lankan Tamils and the waitstaff is from Spain. The novel deals with the lives of two people in this melting pot: Shan, a chef at the pizzeria, and Nia, a recent addition to the team.

Shan, who views London as ‘this contrary indication of motor-loud madness and real, actual breathing life’, has fled from the conflict in Sri Lanka and now lives in the hope that his wife and daughter will soon be able to join him. He thinks of himself as decent and principled: ‘Your honour is the colour of the self, it should be steadfast.’

The young Welsh-Indian Nia, meanwhile, has left Cardiff, an alcoholic mother and a younger sister to join the pizzeria. ‘She would often veer from her happy chatty persona at work,’ we’re told, ‘to such a loneliness when the sun went down, as though the whole of the day’s cheer had been an elaborate gossamer web.’

It's A Big Deal!

30 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 56

India and European Union amp up their partnership in a world unsettled by Trump

The restaurant can thus be seen as a way station for those hoping to move on to better lives in the not-too-distant future. As for the charismatic owner, ‘they were all a bit in love with Tuli, everyone who worked for him in the restaurant’. Nia, in particular, is taken by his charm and bravado, demonstrated in his charitable actions and mysterious associates. She often wonders what makes him ‘possess such a heart, to look outward like that, rather than inward to the hidden pockets of the self as she did’.

The novel progresses in chapters that alternate between the lives of Nia and Shan as they gingerly navigate unfamiliar territory. Along the way, their backstories are tunnelled into and contrasted with present circumstances.

Nia tries to find out more about Tuli’s seemingly altruistic actions, while Shan pursues the ambition of getting his immediate family to join him. The plot does begin to sag in the middle, but soon moves into higher gear as circumstances force the three of them to set off on a personal mission.

Lalwani’s prose is insightful and rich in metaphor. Nia’s anger is ‘tight and burning like tobacco in a pipe’, while Shan’s job is ‘a pearl in the vast gloom of oceanic sediment that was his life’. In the restaurant, a bowl of wooden cocktail sticks resembles ‘soldiers sleeping in a mass’, while on another table, the transparent forms of glass bottles are ‘as defiant as nudists on a beach’. Such language can occasionally fall into the trap of becoming overheated, such as when a character enters a room’s ‘gloaming void’.

The ostensible purpose of You People is to comment on the arbitrariness of immigration laws, especially the inequity of treating human beings as numbers. However, the novel goes beyond this to explore a spider’s web of ethical considerations. When the boundaries between ends and means are blurred, there’s no simple matrix of right and wrong in this rock-paper-scissors world.

It’s an issue that doesn’t lend itself to easy solutions, but the tales of those on the coalface can offer depth and dimension. In his impassioned polemic, This Land Is Our Land, Suketu Mehta writes, ‘The first thing that a new migrant sends to his family back home isn’t money; it’s a story.’ Lalwani’s You People is among the stories worth listening to.