Love and Labour

FEW BOOKS ELICIT all responses. But while reading Shrayana Bhattacharya’s Desperately Seeking Shah Rukh: India’s Lonely Young Women and the Search for Intimacy and Independence I found myself adding “Important”, “Haha” and “ugh” in the margins. I star the parts that reveal surprising (and often uncomfortable) truths: 80 per cent of farm work is done by women; an urban Indian woman spends five hours on household chores every day, whereas an urban Indian man spends 29 minutes on house work every day. I highlight the line that says just over eight per cent of Indians have college degrees. I add smiley faces when Bhattacharya writes that in the 2010s, she could be accused of “dating the who’s who of human crap”. I add a scowl in the margin when a rich Delhi brat named Varun tells her that men and women, boyfriends and girlfriends can be described as, “A key which can open many locks is a great key. But a lock which has been opened by many keys is a bad lock”. I add an “ugh” when I read about the boyfriend who tells the author at a dinner party, “Only dogs eat in public. Put the plate down, you don’t need the food.”

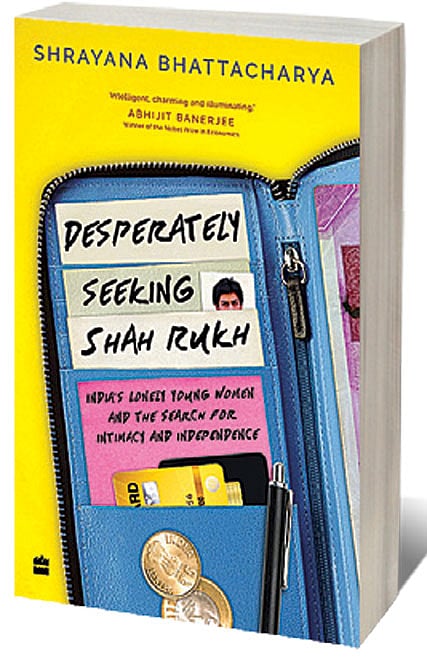

Desperately Seeking Shah Rukh written by a trained economist about a film star is an odd book. And odd in the best way, which means it defies easy classification. Bhattacharya combines her two great passions—economics and Shah Rukh Khan—to write a book that endears and enlightens. Born from 15 years of reporting and “eavesdropping”, it is a book that is about women and work, loneliness and intimacy, feminism and film. It interrogates the nature of both icons and fans, privilege and inequality, love and romance, autonomy and achievement. And it does this through a robust storytelling method by combining reportage with research and data. Many books deal with a spectrum of issues, but this one is particularly enjoyable for the register of emotions it employs, from rage to reconciliation, heartbreak to determination, levity to gravity.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Shah Rukh Khan forms the backbone of the book. A common fandom unites the different women characters whose lives are chronicled, starting with the author. The club that Bhattacharya pieces together comprises women who “find emotional comfort in an actor as they seek to realise their ambitions for a life of love and dignity.” The film aficionado will pore over film analysis, of which there is plenty. But what stands out is Bhattacharya’s zeal for nuance. She is a fan. She talks to fans. But her dedication leads to intellectual rigour and not blind devotion. “He isn’t a feminist icon,” she writes, “but certainly a female one”. This is because his movies give comparatively more room to women’s thoughts, words and actions.

The women she speaks to range from Vidya, a Brahmin engineer, an “Accountant” from Rohtas Nagar who is no ordinary accountant, but a “gazetted accountant”; Gold Mendiratta, a flight-attendant who is “certainly the first person in [her] family to date” and who finds happiness with a Captain America; Zahira, an agarbatti maker in Ahmedabad; to Manju, a garment worker in Rampur, Uttar Pradesh.

Through the accounts of Zahira and Manju, Bhattacharya raises fundamental questions: What is work? Who is a “working” woman? What is the life of a working woman? Must she be in an office for eight hours? What of the embroidery worker in Rampur, who embroiders when domestic chores allow her? How can labour laws or minimum wages or social security be given to these women, as after all 70 per cent of women employed by the textiles and garment sector in India work from home? How can society and the economy treat them fairly?

A feminist book such as this is too smart to promote “smashing patriarchy”. It lays bare the physical and psychological labour of women, reminding us that families are “fulcrums of discrimination” but also emphasises that freedom is not always won through revolution, but through incremental change. It is a book to be celebrated, as it is finally about women seeking a different reality for themselves, with a little help from their favourite icon.