Losing Faith

WHEN MIDHUN ENDS up in the ICU after his bike meets an accident on a Delhi highway, his friends hope the worst is over. He’s lost some skin on his arms and legs, and has a small injury on his head—but the doctors reassure them that there’s nothing to worry about. The next day, however, his condition worsens. There’s an internal haemorrhage that didn’t catch their attention earlier. Midhun is soon pronounced braindead, and his organs make their way in different ambulances to give a fresh lease of life to six people across the country.

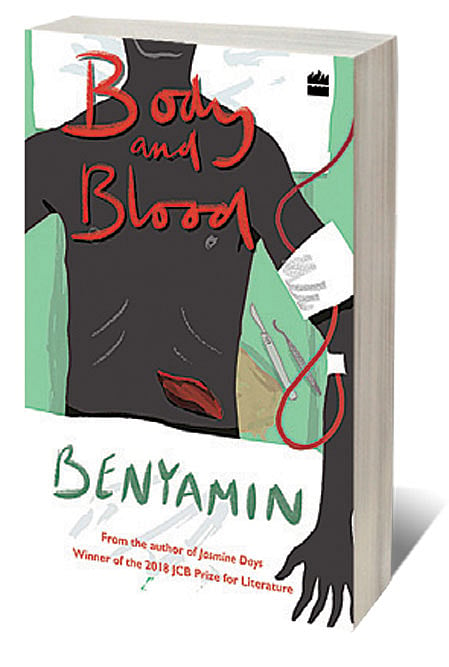

As his friends try to come to terms with his sudden death, Ragesh says to Rithu on the phone, ‘Why did God do this to the meekest man in our group? What then is the meaning of the faith that we found in the prayers that we pray?’ He wonders how his atheist parents continue to live more happily than them. It’s a crucial moment in Body and Blood, Benyamin’s latest novel. The friends—Ragesh, Rithu, Sandhya and Midhun—are part of the same fellowship in Delhi, where they gather every Saturday to sing songs, pray, read the Bible and listen to the Gospel. This shared sense of faith and community fosters a kinship among the four, all outsiders who have made Delhi their home.

It's A Big Deal!

30 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 56

India and European Union amp up their partnership in a world unsettled by Trump

Like in the much-acclaimed Goat Days (2008) and Jasmine Days, which won Benyamin the JCB Prize in 2018, migration and belonging form the crux of Body and Blood too. The author takes a departure from writing about the Middle East, setting the story in Delhi and taking readers to Goa, Chennai, Bhopal and other cities as the three friends try to piece together the events leading up to Midhun’s death.

The fellowship is run by Pastor Sam Philip, a larger-than-life personality who cites his own story of being rescued from the clutches of poverty and death to inspire people to join the fold. Benyamin makes Rithu’s character the most intriguing—she’s judicious and inquisitive, and is the one who gets Ragesh and Sandhya to dig deeper when an anonymous tip on her phone indicates that Midhun’s death may not have been an accident.

There’s also a farcical passage on televangelists and their ‘healing sessions’. Rithu discovers much to her shock that the girl in the video who heals from two illnesses at different points in time is her friend. Benyamin also weaves in the real-life story of Alvares, the high priest who had walked out of the Church rejecting the Portuguese’s dictatorial behaviour, and chose to serve the poor and the sick. While translating stories about him from Portuguese for her father’s book, Rithu is faced with a dichotomy around the idea of faith and selflessness.

Body and Blood sent me down a rabbit hole of reading around prosperity theology—jogging faint childhood memories of watching televangelists working miracles on people with supposedly serious ailments.

Benyamin, a practising Christian himself, has stated that he’s against prosperity theology—it was a news item about the arrest of a doctor in an organ donation scam that inspired the book. It’s an interesting time to read about faith, particularly the capitalist evils that organised religion can spawn—and one can’t help but think how the novel would have been received if the religion in question was not Christianity.

Benyamin writes with admirable simplicity—the narrative is tight and quick-paced—and I finished the book in two sittings. It’s telling for an author who never aspired to be a writer, or spent time fraternising with litterateurs or editors. In an interview around Yellow Lights of Death (2015), he was not dismissive of comparisons with Dan Brown, explaining that “if you can’t hook the readers in the first five pages, you’ve lost them”. Body and Blood keeps you hooked till the very end.