Languorous Unfoldings

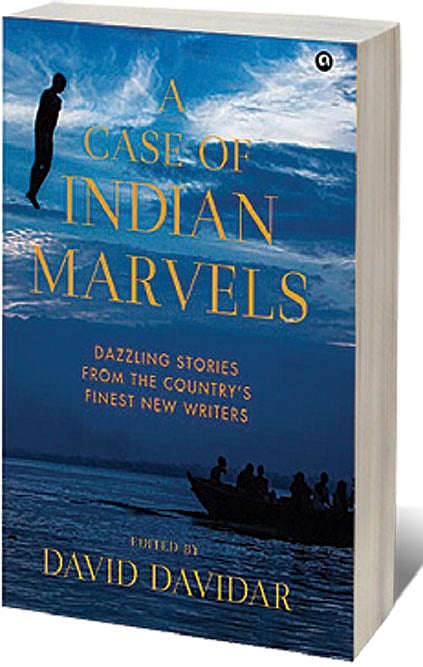

ONE OF THE key virtues of a successful short story, as David Davidar argues in his erudite introduction to A Case of Indian Marvels, is its effortless readability. “Line after superb line creating a narrative so compelling that the reader wants to keep reading,” he writes, citing the authority of icons like Bill Buford (former fiction editor of the New Yorker), writer Ruskin Bond, and George Saunders, a contemporary American master of the form.

Davidar’s point is mostly borne out by this anthology featuring stories by Indian writers under 40 (as of 2020). The majority of them write in English, though there are a few in translations from other Indian languages. The lengths of the stories vary—from the brevity of a Kafkaesque parable (Tushar Jain’s ‘The Octopus: A Fable’) to the languorous unfolding of ‘Lorry Raja’ by Madhuri Vijay and ‘Gul’ by Shreya Ila Anasuya. So do the themes, though there are curious overlaps.

Mughal nostalgia, legends retold from ancient myths, political hot takes masquerading as fiction, grinding poverty, and dystopias where no one can breathe without oxygen tanks—these are some of the common concerns of these writers. Given the preponderance of Indian writing around these topics, especially over the last decade, one isn’t surprised. The writing is almost unfailingly competent. Even the irksome second-person voice, in the few instances where it appears, is handled with the polish of A-league MFA graduates.

But there is skill that’s perfected through years of practice, and then there’s something more. And it’s the quest for this elusive ‘more’ that compels the reader to keep turning the pages. Luckily, every few pages one strikes gold. In fact, starting with the opening story itself (‘The Alligator of Aligarh’ by AM Gautam), where the seemingly cliched social realist mode takes a surrealist turn in the concluding paragraphs.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

If a handful of writers venture into the realm of the supernatural unabashedly, others teeter on the edge of it. In ‘The Annual Pig Parade of Kharagpore’ (my favourite in the collection) by Nicholas Rixon, the centrepiece is a macabre ritual in a small Indian town that spins out of control. The unfolding, though bizarre and incredulous, is so arresting that the reader is willing to suspend their disbelief to get to the end of the matter.

Then there are tales steeped in the everyday but crackling at the edges, quick to jolt the reader into reckoning with stuff that’s usually hidden under the carpet by Indian families. Eccentric grandmothers and wilful child narrators—there are several of both—seem to be the agents of such disruptions. In ‘My Grandmother Talks About Shit’, Srividya Tadepalli brings alive a dotty grandma who launches into a diatribe into the wee hours. Pritika Rao’s ‘Spider-Girl’ does not aspire for complexity but manages to evoke a gasp of surprise in the end that a classic short story is supposed to. In Bhavika Govil’s ‘Eggs Keeping Falling from the Fourth Floor,’ a young narrator glimpses a gruesome end to a life of abuse and mental illness, the full horror of which the reader is left to process.

The best stories in the collection go beyond gimmickry and cliff hangers to arouse pathos and wonder and, less often but no less powerfully, delight and laughter. Several others, though written with panache, feel a bit antiquated (‘The Power to Forgive’ by Avinuo Kire and ‘The Adivasi Will Not Dance’ by Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar, for instance) next to the freshness of the more experimental voices. Communal violence, identity politics, and marital strife are ubiquitous enough in India to be the lowest-hanging fruits for fiction. But it’s the transformative touch of an expert storyteller, like Kannada writer Shanthi K Appanna (‘Journey’), and their willingness to wager a risk, that elevate a dreary, even irritating, reality—such as a married woman forced to share a berth on an overnight train with a stranger—into a riveting insight into other lives.