Kavita Puri: Breaking the Silence

BASHIR MAAN’S HOME was in the Punjab province of British India—a village called Maan where his forefathers had lived for generations. In the weeks after Partition, Hindus and Sikhs started to flee the village, packing up their belongings into small bundles, leaving behind homes, as they were lived in. Bashir and his friends tried their best to salvage the remnants—utensils, beds, sheets—from looters and transported them to a storeroom in a nearby gurudwara.

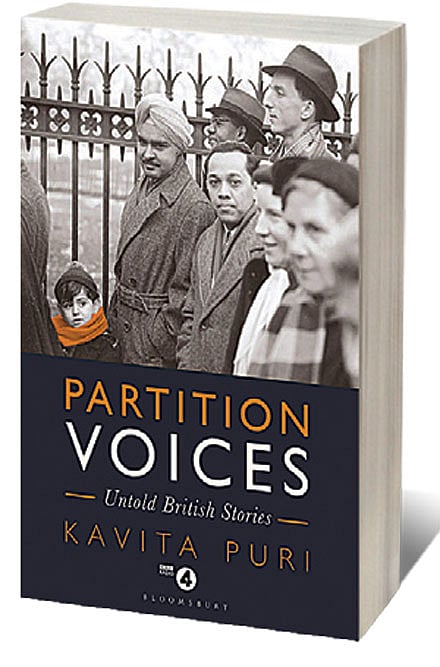

These would help Muslim refugees trickling in from India start a new life. ‘People who could not share the same land would be sharing something even more intimate: the bed and bed sheets of the other,’ writes Kavita Puri in Partition Voices: Untold British Stories (Bloomsbury; 320 pages; Rs 499).

Today, 91-year-old Maan lives in Glasgow with his family—from a pedlar selling clothes from a suitcase after arriving in Glasgow in 1953, he went on to become a member of the Scottish Labour Party. On the wall of his study hangs an Order of the British Empire, from the queen, for his work in public life in Glasgow. Maan’s story is one of the many that Puri has chronicled in her seminal book based on South Asians who migrated to Britain after Partition.

The book is an extension of her BBC Radio 4 series—Partition Voices—in 2017 that documented these stories around the 70th anniversary of Independence. The BBC journalist embarked on the project after hearing her late father’s account of what he had witnessed as a 12-year-old, as his family fled Lahore for Moga in Punjab. He immigrated to England in 1959, but didn’t speak about his experiences

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

until a few years ago.

“Many people like him kept their silence, it was a survival mechanism of sorts. Life was pretty hard here in the ’50s and ’60s—their generation was fighting to be accepted in this country, for equal pay and against racism. Some of them may have been doing jobs that were slightly beneath them, so they also had to fight for promotions. If you thought about what you had left behind, how were you going to progress? There wasn’t time to dwell on the past,” says Puri, speaking on the phone

from London.

The wider institutional silence about the Partition and the Empire in Britain—it’s not even taught in schools, Puri adds—meant there was no platform for them to air their stories. With the 70th anniversary though, the narrative began to tilt. The generation that had survived the catastrophic events was now elderly and wanted to talk about it, have their stories recorded. Their children and grandchildren too wanted to know their history—being second and third generation immigrants, their understanding of identity (in Britain) was complex.

The book is structured in three parts—End of Empire, Partition, and Legacy. End of Empire also includes British colonial accounts like those of Pamela Dowley-Wise and Kenneth Miln, both of whom were born during the reign of the East India Company. Puri says that though their experiences were vastly different, she wanted to showcase how the histories of the British and the Indian subcontinent were intertwined. “Because I was doing it from a British perspective, it was important to me that the wider public in Britain today realise what it was like… many young people don’t know that the British ran India.”

In the introduction to Partition Voices, explaining how the division was broadly across religious lines, Puri delves into how the border was imagined throwing aside practical, physical realities. ‘The new border crossed agricultural land, cut off communities from their sacred pilgrimage sites, paid no heed to railway lines, and separated industrial plants from the agricultural lands where raw materials such as jute were grown,’ she writes.

“It was so ill-thought through and rushed. How can you divide a nation in 10 weeks? And the Partition line was announced two days later, on August 17. People remember literally sitting around the one wireless the village had, or waiting for a newspaper to get delivered or word-of-mouth on whether their village was in India or Pakistan. They had suitcases ready in the eventuality that they would have to leave,” she says, adding, “It was the same for my dad in Moga. They had packed a bag and were ready to leave, but didn’t have to. It’s impossible to conceive that kind of situation.”

In addition, people who were forced to cross the border didn’t realise that the move would be permanent. Khurshid Sultana, one of the interviewees, recounts how her maternal grandmother buried all their jewellery in the ground thinking she would be back. “They thought they would be back in a few weeks so they didn’t take that much stuff with them. Many handed their keys to their neighbours. What’s heart-breaking is you speak to these elderly people and they say ‘I never got to say goodbye to my best friend, and we could never get in touch. I want to go back, I want to see if he’s still alive.’ It’s so sad, and these things never leave you, even when you’re 85 years old.”

Puri writes that the numbers killed in Partition violence will never be known, ranging between two lakh and two million, depending on the source. Gurbakhsh Garcha, an interviewee, remembers weeding in the fields near the railway lines and how the groundnut crop grew lush in random patches. It had been fertilised by the bodies of those who had died on the journey. The collateral damage, says Puri, was staggering. “It was the largest migration outside war and famine. The numbers are so huge, the events so cataclysmic that you can be blinded by that. But only when you drill down on the stories, all epic in their own way, that you realise how utterly life-changing it was.”

Puri references Urvashi Butalia’s The Other Side of Silence in the book while delving into the violence meted out to women during the period. When she was looking for interviewees, an overwhelming majority who volunteered were men. With women’s bodies becoming the battlegrounds for settling religious scores, many of the voices were consequently lost, shrouded in shame and loss of honour.

“We never spoke to anyone who had been raped or abducted. I think these stories will never emerge in Britain now. The women we did speak to told of their visceral fear of sexual violence and of rape committed against friends. A female interviewee spoke about how her grandmother stood up to the males and refused to allow the women to be killed in the name of honour. To me, this was an unexpected story of empowerment,” she says.

The stories of the women do emerge in accounts of the male interviewees, many gave eye-witness testimony of abductions and bodily mutilations. Iftkahr Ahmed, who’s retelling is particularly distressing, recounts how young women were picked up by Hindu men, and he had no option but to walk on by as to protest meant certain death. “To this day he still remembers the cries of the parents. People felt impotent to act,” says Puri.

The hardest stories to tell were of the ones who had witnessed the violence first-hand, or were inadvertently party to it. Fifteen-year-old Swaran Singh, as the eldest son in the family, was chosen for a revenge attack by elderly Sikh members. While he didn’t harm anyone, he had to hand over his sword to an adult, and watch a Muslim man being killed. The sword was then wiped and handed back to him—the day of killing has never left him. Puri adds that Khurshid’s fear as a woman travelling by herself in the train’s ladies’ compartment is still palpable today.

“None of these people had any kind of post-traumatic counselling. The incidents affected them all in very different ways, and just like WWI soldiers, they had to deal with it all on their own. And often in their heads as they weren’t talking to even family members about it.”

PURI SAYS BEING sensitive to the interviewees was a prime concern. She met them in their homes, with family members around so they felt safe. It was Karam Singh Hamdard’s story that left her feeling the most unsettled. The octogenarian was attacked with a poisoned spear in his arm—the scar is a permanent reminder of the day.

While his father was killed by a Muslim mob, his sister was saved by their Muslim neighbours. “He still can’t reconcile those two things today. No one thought it would descend into this bloodbath,” she says, adding that she still thinks about him for how upset he was while narrating the story. “Often I would say in the middle of the interview, ‘let’s stop now’ but he would say no. He wanted to it to be heard and recorded. They’d never seen their story in that kind of big way before, and only later did they realise they’d lived through a monumental period in history.”

During the Partition, refugees left with the bare minimum—even if they did take something to remind them of home, it was lost on the way. Some of the interviewees have visited their homeland in the years since and picked up little mementos. Mohindra Dhall got a brick from his childhood home in Lyallpur (now Faisalabad), and it now sits in a glass case in his Edinburgh living room. Another interviewee, Raj Daswani, has stones from Karachi in his study—he kisses them and says they make him feel like he’s still connected to his soil. “These mementos represent so much and it’s touching to see them talk about it, a reminder that the land was theirs too.”

Puri believes that it’s impossible to grasp the make-up of contemporary Britain without understanding its colonial past. She writes that the double displacement South Asians went through has been passed down the generations—the obsession with owning property, getting the best marks at school, becoming a doctor, can be traced back to that feeling of insecurity.

“When you realise that things can turn so quickly, like it did for my father’s generation, it makes you more mindful, and not complacent about your place. This is a British national story, even if it’s not been framed that way. If you don’t understand Empire and how it ended, you can’t understand migration to Britain, why it looks the way it does today and why there are so many South Asians in this country,” says Puri.

Most importantly, the refugees’ memories and stories of living in undivided India are a way to ensure that future generations can’t deny that different religious groups had been living peacefully together for centuries. “Their generation is the last people that can say ‘I was a Hindu living in Lahore’, or ‘I was a Muslim living in Amritsar.’ That is now pretty much relegated to the history books. When Gurbakhsh’s uncle’s mother, a Sikh, died prematurely, her Muslim best friend breastfed his uncle. What can be more intimate than that? That is another side of history that needs to be told,” she says, adding, “And that’s what left me hopeful at the end. They don’t want just the stories of violence to get passed down. In Britain, in India, in Pakistan, we must listen to these testimonies. They are telling us something important and powerful.”