Feast of the Dead

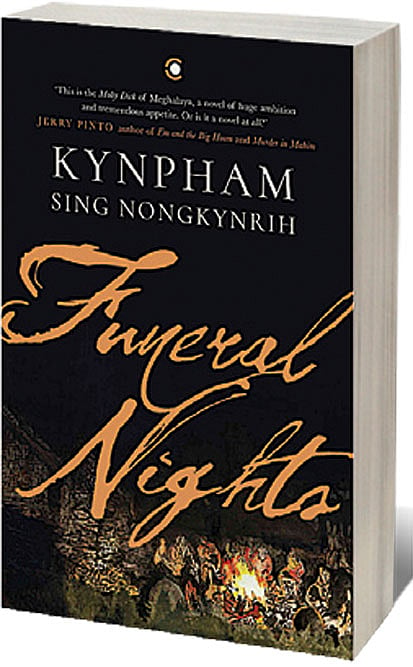

IT’S ALMOST IMPOSSIBLE to navigate Khasi writer Kynpham Sing Nongkynrih’s magnum opus Funeral Nights without sensing his poetry. To bring to life death rituals requires sensitivity—especially now in a post-pandemic era, when death has visited so many. I recall Kynpham’s 1994 poem ‘Ka Jingphuh Tit’ (‘The Fungus’); “Where I live it is cold and dark inside / So cold you never know how warm the day is, so dark you never know its hour”. Fragments of his verses and his love for poetic voices in and around Meghalaya traverse this thousand-page book. It defies classification as it blurs the lines between fiction, nonfiction and travelogue. In a unique way, it bends different genres, history, storytelling, ethnographic references, poetry, fiction, travel anecdotes etcetera.

This is also why the diverse subjects that Kynpham deals with—Sohra (his hometown), Khasi pride/identity, rituals, origin tales, myths, folklore and more risk overwhelming the reader. Kynpham’s debut fiction reminds one of Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron and One Thousand and One Nights. Based on Ka Phor Sorat, a feast of the dead among the Lyngngams, a Khasi sub-tribe of the West Khasi hills, this book doesn’t lapse into melodrama or run the risk of aestheticising funerals of the community in a memoir form. Funeral Nights thus strains against mere literary analysis, because grieving for the dead is, after all, “Time lived, without its flow” (according to Denise Riley, an English poet and philosopher).

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Kynpham tries to capture temporality in all its essence. This narration transforms the poet and author into traveller. The ambition is commendable and there’s a deluge, which few will be able to hold on to. Yet, Funeral Nights is also conversational and humorous in its meditation on the past, present and the vulnerable future of the Khasi hills in northeast India.

A few works on Shillong that encompass debates of belonging in the Khasi hills include Janice Pariat’s Boats on Land, Anjum Hasan’s Lunatic in My Head, Bijoya Sawain’s Khasi Myths, Legends & Folk Tales, Nilanjan Choudhury’s Shillong Times and most recently, a coming-of-age tale by Daribha Lyndem Name Place Animal Thing. Kynpham’s voluminous account however takes a huge leap ahead in content and style—exposing the challenges of narrativising heterogeneity even within the Khasis. This way, the plethora of cultural richness becomes several Venn diagrams across pages—with overlapping and conflicting encounters.

The first few chapters do a terrific job of capturing nuance—for example, in a discussion on “What is a Khasi look,” the character Bah Kynsai and the author recall an incident they faced in Kathmandu. They are spoken to in Nepali due to their “appearances” and this hotchpotch—this inability to locate them racially (partly co-incidental too) adds a distinct flavour to the stories. Similarly, the friends in the village of Nonshyrkhon question their identities, colonial influences, rituals, phonetics of rare languages and the various historical and neo-liberal transformations of the landscape of the hills in Northeast India.

By no means is the sojourn of the friends a simple one. They recount gruesome events and ask uncomfortable questions (about coal mining, forest laws, property issues, violence)—which are politically relevant today. What rescues so many sobrieties in the book are the verses and the enchanting tales, like men turning to tigers and the malevolence of other spirited creatures in the forests.

Moreover, Kynpham’s penchant for writing about the rain contains music for those who can hear it. He says, depending on the nature of rainfall, there are different Khasi names for rain and that in “Sohra raintime is also storytime”. Funeral Nights for all its incisive banality on a death rite is not banal or tragic after all. It contains impeccable Khasi proverbial wisdom contextualised with growing urbanity, which piques its readers’ interest. Finally, it is the author’s embrace of that which cannot be captured that makes this magnum opus an unforgettable journey.