Father and Son

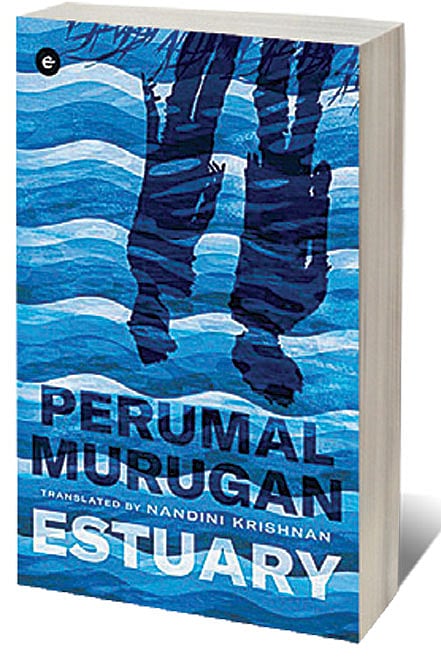

IN ASURALOKAM IS a civil servant named Kumarasurar who, despite being known as a poet of panegyric verses, is unable to have a fulfilling conversation with his own son. Each time Kumarasurar calls Meghas, he sticks to a script of seven prosaic questions, to which his collegegoing son responds cursorily. Despite Meghas’ poor repartee, he insists that his father purchase a more expensive phone for him. Kumarasurar’s enquiry into why leads him down the path of paranoia in Perumal Murugan’s Estuary, a study of generational conflict and conservatism.

The characters in Estuary are asuras and asuris, often depicted in Hindu mythologies as demigod antagonists. Yet, this aspect of the novel is barely an aside, leaving some questions about why it wasn’t utilised further. Only rarely, such as a passing mention of how a two-headed andaranda bird could be hired to cart a man away, are the fantastical possibilities of the setting explored. Aside from their looming sizes, Asuralokam’s inhabitants are exactly like human beings. The author says as much in the foreword and hints at deliberately writing a ‘deviant’ novel.

Kumarasurar and his wife, Mangasuri, are devastated when Meghas opts for engineering rather than medicine as a course of study. Parting with him at a boarding school so oppressive that graduating students assault teachers as they leave isn’t so difficult for them, but college is a different story. All over Asuralokam are engineering colleges that take the real repression of Tamil Nadu’s institutions just one or two logical steps further: there are bridles for students, so that they focus exclusively on studies (parents request new designs that also limit speech), branded canes to administer scarfree corporal punishment (with parental endorsements like ‘cooling smoothness’ and ‘the feel of a cat’s fur’), and more such abuses. Kumarasurar is appalled, but when Meghas finds a more liberal institution, the father’s relief is mingled with horror about what he may encounter there.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Gradually, Kumarasurar begins to unravel, experiencing hallucinations and morbid thoughts as he imagines Meghas falling prey to temptations such as death-defying selfie-seeking stunts, spending time with girls (Asuralokam’s other engineering colleges replicate India’s gender-segregation and skewed gender ratios) and so on. The more he is introduced to the world as being a less rigid place then he thought, the more distraught he becomes. It is as though as Kumbhas, a colleague who answers his questions about pornography without inhibition, notes: ‘Kumarasurar was the only one who was clueless about the world they lived in.’ As the novel progresses, it becomes clear who the subject of this subtle satirical work may be. At the outset, it seems like it’s about the average contemporary Tamil man, who wants the best for his children but doesn’t understand the world they live in. Perhaps it is that too.

Yet, a little consideration of the context reminds one of how Perumal Murugan was forced into exile from his hometown of Tiruchengode in 2014, following a controversy about his book Madhorubhagan (translated into English by Aniruddhan Vasudevan as One Part Woman). The situation was arguably fuelled by those in whom ignorance had festered to the point of fundamentalist ire. Estuary compassionately suggests that there is a fine line between the person who becomes preoccupied with perceived threats and becomes a danger to themselves and others, and the person who chooses to overcome their fears and expand their perspective instead. ‘Everyone lived within a set of boundaries that circumscribed one’s life. When one stood within one’s ambit and looked at someone else, it appeared the other person was crossing his limits. When they were circumscribed by invisible lines, how could one tell what was right and good within the boundaries?’

Kumarasurar ponders in the closing chapters, having had the simplest brush with freedom. Perhaps this opening of the mind and spirit is what the author, much besieged, is able to wish for his erstwhile detractors now.