Empresses of Maladies

WHAT IS IT about cancer that makes everyone confront their true selves? The malevolent twin of our good cells, the disease lurks deep in our blood, a genetic code that usually outlives death. And even now, in the age when travel to Mars and self- driving cars seems possible, it is undefeated, undiminished and unconquered.

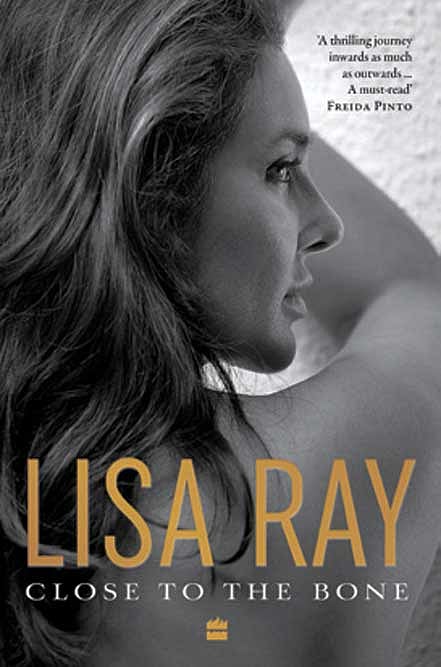

How human beings deal with that finality is what defines them. Especially because, as Lisa Ray writes in her recent memoir, Close to the Bone (HarperCollins; 386 pages; Rs 599), modern medicine doesn’t know what to do with the survivor once the treatment is over. As cancer’s brilliant biographer Siddhartha Mukherjee has written, the story of cancer isn’t the story of doctors who struggle and survive, moving from institution to another. ‘It is the story of patients who struggle and survive, moving from one embankment of illness to another. Resilience, inventiveness, and survivorship—qualities often ascribed to great physicians—are reflected qualities, emanating first from those who struggle with illness and only then mirrored by those who treat them.’

In an emerging new genre in India, cancer warriors/graduates/ survivors are chronicling their stories, in books and on social media, with wisdom, courage and often a healthy dose of humour. No shrinking violets here. These survivors, almost all women, are owning their illness, showing off their shiny, new bald pates on social media, like actor-writer Sonali Bendre, or documenting the return to fitness via gym videos in the case of Tahira Kashyap writer and wife of actor Ayushmann Khurrana. With appropriate hashtags like #SwitchOnTheSunshine in the case of Bendre, and just the right selfie pouts in the case of Kashyap, they have become ambassadors of hope, breakers of stigma and shatterers of shame. As Bendre wrote in her July 4, 2018 Instagram post announcing her Stage IV cancer, with only 30 per cent survival rates: ‘Sometimes, when you least expect it, life throws you a curveball.’

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

Few have dodged this curveball as effectively as actor Lisa Ray, whose Close to the Bone is as much a personal history as it is a memoir of the cancer that struck her in 2009, just a year after her beloved mother’s death. Much of the memoir has to do with understanding who she is, and it begins, as always, with her parents, the shy Bengali scientist from North Kolkata and the gregarious, ever-active Polish woman from Warsaw. An unlikely couple in 1960s England, they travelled bag and baggage to Toronto, Canada, part artists and part adventurers, as all immigrants are.

Ray becomes a model after being spotted on a visit to India and is soon plastered over hoardings and magazine covers, re-imagined as a sex object in a now famous red swimsuit and black cat suit by Maureen Wadia. Negotiating a lifelong problem with food (eat, fist-down-the-throat, purge, eat, repeat) and low self esteem further denuded by Mumbai’s bitchy society czarinas and the unquestioned nastiness that passed for celebrity gossip in the early ’90s, she becomes part of the set of permanent exiles in Mumbai. With her multiple myeloma in remission now, after she submitted herself to chemotherapy, stem cell transplant, and a clinical trial of a cancer-killing gene called nk-92, Ray is now back in the city of dreams, Mumbai, this time with twin daughters and husband, Lebanese-Canadian Jason Dehni.

It’s a happy-ever-after, but only because Ray chose love, liberty and joy, over whiny self pity and never ending gloom. It’s a miracle because cancer is not the first terror she has faced. She escaped a car accident that paralysed her mother for 18 years, an attempt on her life by a rejected lover, and countless attempts to stifle her spirit by a particularly thuggish married boyfriend. But she’s here now, star of a new Amazon show, Four More Shots Please! where she plays a lesbian superstar Samara Kapoor, and is looking to make a career from writing. As she says now: ‘I inhabit truth much better than the masks. I would rather stand here and display my wounds.’ No matter how deep or how ugly they may be.

It’s the same desire that grips Manisha Koirala in Healed: How Cancer Gave Me a New Life (Penguin, 2018; 240 pages; Rs499). Written with Neelam Kumar, it details her descent from one of Bollywood’s biggest superstars, actor in movies as varied as Vidhu Vinod Chopra’s 1942: A Love Story to Mani Ratnam’s Bombay to a perpetually exhausted and irritable actor feeding her ego. She had just finished a film called Lawaaris in 1999, was doing 12 movies a year, and felt like an automaton. That was when she started drinking, usually one bottle of Vodka or wine a day, partying with friends at her home or theirs, and punishing herself.

Much like Ray, Koirala doesn’t spare herself. She speaks of how unforgiveably she behaved towards her friends, whether it was Feroz Khan, who would address her fondly as his Manish, or Divya Bharti whose prayer meeting she breezed in and out of. She confesses she had been seeking the wrong reasons to be loved, entering one toxic relationship after another. By the time ovarian cancer finds her, it is stage IV and has metastasized, having spread through her stomach like rice krispies.

LIKE RAY, KOIRALA also focuses on post operative care. Like Ray, she embarks on her own spiritual journey, in this case cosseted at home by an expert nutritionist, a meditation master and another friend who taught her meditation the Osho way—it’s what she calls her Team Mumbai. And when she worries, with natural vanity, about the staples all over her once beautiful white skin, the nurse replies nonchalantly, “You shouldn’t be scared of these; what is inside you is far more dangerous.”

And imagining that inside his beloved child is what Emraan Hashmi had to do, when his child is stricken with cancer. In The Kiss of Life: How a Superhero and My Son Defeated Cancer, (with Bilal Siddiqi; Penguin, 2016; pages 304; Rs399), Hashmi writes of how his son was diagnosed with a rare case of kidney cancer in 2014 at the age of three. Finally, it was only five years later, that Hashmi was able to declare on Twitter: ‘Today, 5 years after his diagnosis Ayaan has been declared cancer free. It has been quite a journey. Thank you for all your prayers and wishes. Love and prayers for all the cancer fighters out there, hope and belief goes a long way.’

The best memoirs are like travelogues, taking you on a journey of the soul as much as of the world. And so it is with Ray who writes with fondness of the girl she was when she visited Shyambazaar in Kolkata during her vacation—‘in my head I was a brown-skinned doe-eyed glucose-eating meye (girl).’ Another minute she wanted to be French actress Isabelle Adjani from the chic pages of Vogue, ‘like a cat. Whatever she does, she sets up in a corner and makes it her own. And one day you wake up and she’s gone.’ Her life takes her from Toronto to Kolkata, from a small village in Croatia, from the streets of London to the high towers of Mumbai, from a Parisian flat to a Swiss town. Always accompanied by pain. ‘Life is hard, alienation trains you to value connection, pain is a great teacher and sadness is a precondition to a tender heart,’ she writes.

And if cancer teaches anything, it is love. For both Ray and Koirala, the ultimate love is that of their mothers. The more Ray flies away from her mother, the more she feels the void. The more Koirala suffers, the more she sees it mirrored in her mother.

Cancer eventually, if you can beat it, is about reinvention. Much like a stem cell transplant gives you a new body, cancer gives you a new life and identity. Koirala, on the cusp of 50, is completely different from the shy 19-year-old who had just come to Mumbai from Kathmandu, more interested in partying than reading Ayn Rand. Ray, a mother now, knows the reality—that everyone who is born holds a dual citizenship, in the kingdom of the well and in the kingdom of the ill, as Susan Sontag wrote. Ray holds nothing back. The Botox, the brutish boyfriend, the often brattish behaviour, the ‘diet of commotion and inflated drama’. She has lived her life like a lotus flower and earned her freedom through struggle.

What draws us to these cancer memoirists? Harper Collins CEO Ananth Padmanabhan believes personal narratives “about confronting mortality and recognising the true value of life, and living simply and happily, can be restorative and have a deep impact on how we view our very existence”.

Indeed Paul Kalanithi’s When Breath Becomes Air or Randy Pausch’s The Last Lecture remain the gold standard of preparing for a good death. As Atul Gawande says in Being Mortal, ‘Medical professionals concentrate on repair of health, not sustenance of the soul.’ And what such a close brush with death gives you is the opportunity of a do-over, of reinvention, of remaking oneself. As Koirala’s commissioning editor at Penguin Gurveen Chadha puts it: ‘Healed is a thoughtful and compelling exploration of what makes life meaningful after a heartbreaking diagnosis.’ The opportunity to know what lies after resurrection. And of confronting your fears.

As Koirala writes of her mother leaving her as a child with her grandmother, ‘It was only years later that I understood why she had left me there. She was helping my father in Nepal’s mounting political activities and knew that my grandmother, who had ably raised several children, would look after me well.’ But, she goes on, ‘The fear of being abandoned had chased me all my life. This fear, however, was unlike anything I had experienced before. It was the fear of being abandoned by life itself.’

As Hashmi writes in The Kiss of Life, ‘As adults, we are always preoccupied with the baggage we carry and are afraid of our burdens.’ Nothing cures that fear more effectively than facing cancer.

What can we mere mortals learn from these accounts? As Ray’s words, remind us, ‘What do you care about the most? What matters? Pursue that. Forget the rest.’