Curse of the Caricature

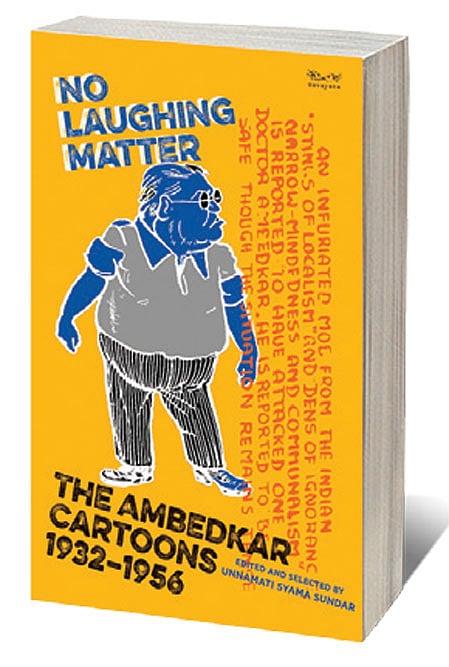

AT FIVE FEET seven, Ambedkar was not a short man. Yet, the 122 cartoons culled by Unnamati Syama Sundar for his book No Laughing Matter repeatedly show Ambedkar as the shortest in the frame. So striking is this compulsive dwarfing that the viewer begins to wonder at the perverse perspective shared by the many cartoonists depicting a man who was indeed a ‘tall man’.

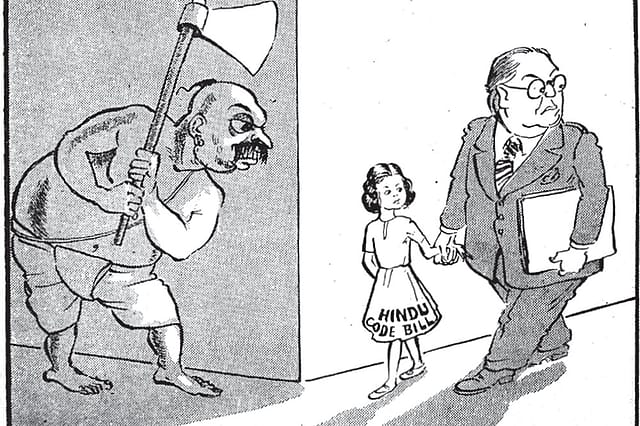

This stunting of Ambedkar does not escape Syama Sundar’s notice in his book, which is an archive of the Ambedkar cartoons drawn between 1932 and 1956 in the English language Indian press. He explains it as the savarna eye belittling the Dalit. But given the number of cartoons that depict Ambedkar not just as short but as a middle-aged, voluptuous woman whose ‘chastity’ and ‘honour’ are repeatedly the butt of jokes, the perspective requires the added qualification of being the male savarna eye. For it is not just casteist intolerance that is on display, but also sexist pettiness. The battle that Ambedkar fought over the Hindu Code Bill is touted as ‘Divorce Made Easy’ and Ambedkar’s 1951 declaration that the Scheduled Castes Federation would talk to different political parties in different states to form alliances is depicted as Ambedkar playing ‘Draupadi’, inviting men into her room. A smiling Draupadi -Ambedkar is shown inviting five savarna men, identifiable by their sacred threads, with a finger held up asking they come one by one.

‘Hitler,’ Adorno wrote, ‘imposes a new categorical imperative on human beings in their condition of unfreedom: to arrange their thought and action so that Auschwitz would not repeat itself.’ A similar imperative is imposed on Indians by a history that is tainted with caste violence and caste discrimination. In order to ‘arrange’ our thoughts and actions to discover ways in which the caste menace can be fought off, and to pave the road that leads away from our varna-Auschwitzes, Indians need to get back to the history lived through. It is this endeavour that Syama Sundar’s book takes part in. The evidence of chauvinism and bigotry he digs out makes us cringe; for the pictures are unabashed in their prejudices; the cartoonists are all renowned and much-feted figures of the Indian mainstream: Shankar, Enver Ahmed (the creator of Hindustan Times’ Chandu), Bireshwar. Harvard scholar Suraj Yengde describes it in the ‘Foreword’ as ‘a museum of the perversities of the elite’. The 2012 furore over the snail and whip cartoon in an NCERT school book was evidently only the proverbial tip of the iceberg.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Syama Sundar divides his book chronologically into seven sections. As a result, the cartoons work as a visual biography of not just the public life of this intellectual and political giant, but also as a showcase of India’s mainstream opinion. Each cartoon is annotated with a short note on the historical context, and future researchers will hopefully make use of this archive with the aim of analysing mindsets and perspectives. Drawing from the English language media, the book gives us a window to the English-speaking Indian elite. The book becomes, in effect, a work that also argues for the media to be wide-ranging and diverse in their origins. That the subaltern speaks is a truth only known when the subaltern voice is heard. Peopled by suited Indians, dhoti-ed politicians and threaded Brahmins, Ambedkar is the only figure here from those marginalised by both caste and class who finds a voice, albeit ridiculed.

Syama Sundar’s book, looking back to an age half a century ago, enables a curious turning of the tables. Looking back at these cartoons with the knowledge of history acquired through the experience of the past 50 years, we find our laughter and derision directed more at those who laughed in those days but have eventually lost to the forces of history.