Beyond Insiders and Outsiders

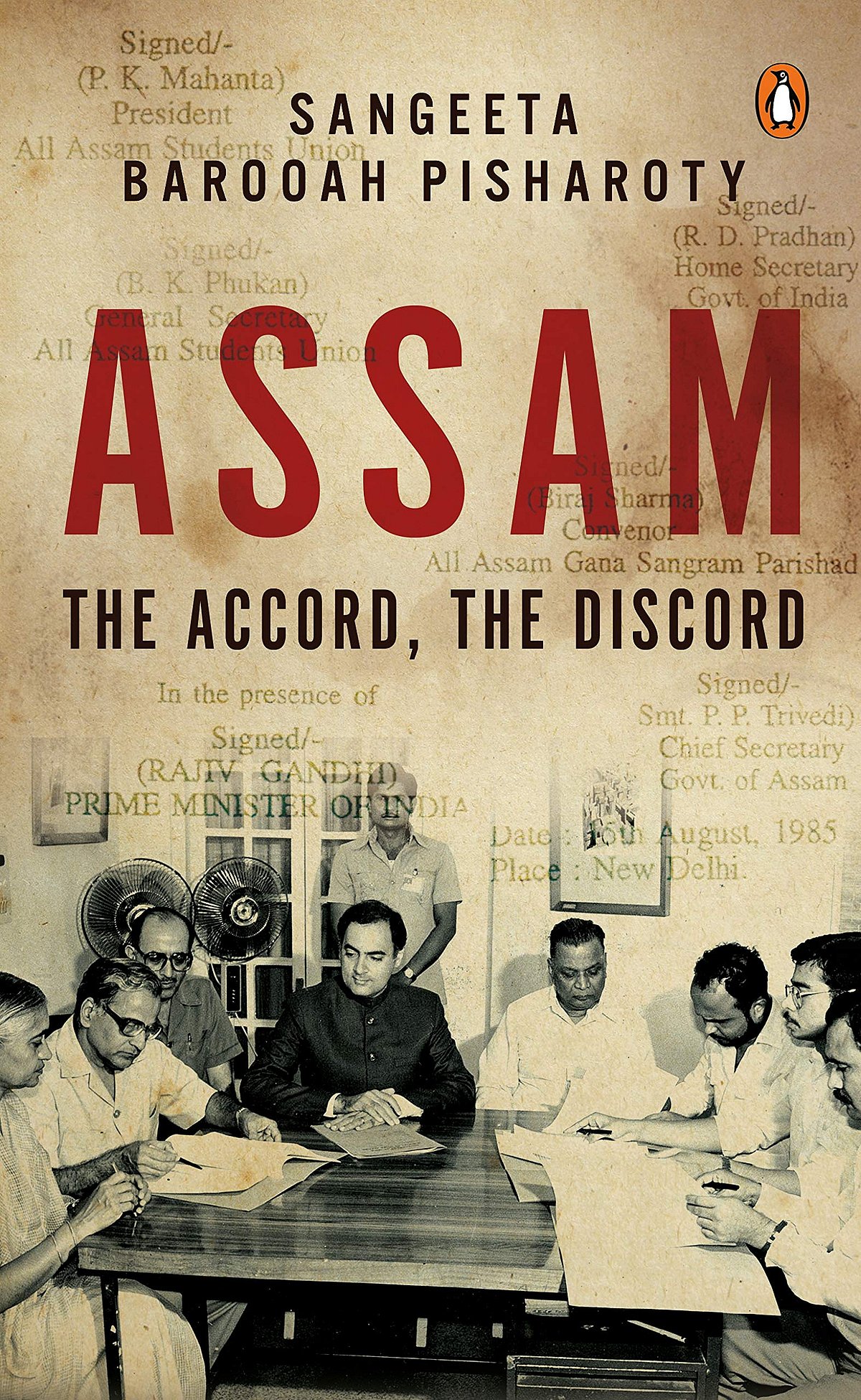

The possibility of a National Register of Citizenship in Assam as a resolution to the perpetual thematic of political life is perhaps dying down after the release of the final list on 31st August 2019. Different constituencies, including the Assam BJP, have already refuted it on many diverse grounds. Nonetheless, the process has generated a lively debate even among those who impugned local specificities thoroughly. Sangeeta Barooah Pisharoty’s book Assam, the Accord, the Discord is a response to such myopic views, and in turn a critical introduction to the ‘Assam problem’. Rather than staging historical materials as the original caterpillar traversing a slippery terrain, the author weaves a long story with both colonial and postcolonial sources, anecdotal contemporary stories and candid interviews of different protagonists at different moments of history. Such methodological pursuits helped her locate a seemingly different gaze on the complex terrain and contradictory pools of reference involving different protagonists within Assam’s political world.

The pioneering attributes of the book lie in author’s staggering disclosure that ‘each player, in the course of time has become both a victim and a perpetrator in each other’s eyes’. Insights such as these produce multiple paradigms of multicultural temporalities and is a marked shift from the straitened community representation dilemma which has often been the case of North East English language writings for some time. The engagement of communities in recent times with each other evolved from different historical pitfalls and how these historical events complicate the skewed terrain of identity politics has mostly been ignored in the recent debate over NRC. Invoking the Hindu Bengalis, Nepali and the Eastern Bengal origin Muslim communities and their side of the story in relation to the issue of partition, the question of land unfolds the layers and complexity of the ‘Assam problem’. It is not that these issues have never been discussed before, but introducing them together as part of the complex problem produces a holistic imagination that eventually disturbs the often cited indigenous versus outsiders discourse. Instead of the marked contemporary political geography of Assam as the authentic abode of the claims of indigeneity, the author also looks at the plights of the people she terms as ‘Assamese’ staying in present day Bangladesh and Myanmar.

Modi Rearms the Party: 2029 On His Mind

23 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 55

Trump controls the future | An unequal fight against pollution

Such narratives, however casual they may seem, articulate a frontier of shared geography, ideas and cultural practices narrowed down by partition politics eventually. In such a context, Pisharoty’s reading of the Assam movement, its commencement and gradual articulations, the reading of Nellie massacre in different lights and layers, and finally its culmination in the process of updating the National Register of Citizenship specifies the significance of contemporary politics in the region to its readers.

However, despite its narrative success, the book’s inchoate belief in the idea that every catastrophe of Assam shares a burden of history is rather naïve and invites caution. History, one should remember, is not a passive prerogative but is actively remembered, distributed in contemporary politics. The idea of NRC and so called consensus over it is not exactly a historical culmination of certain sub-national demands. As the author rightly puts it, the idea itself was generated by the Congress government in Assam even though it was not a mandate of the Assam accord. Such state interference or its temporal strategy has continuously been, whether covertly or overtly, a general practice in this part of the world. Without recognising such practices, its continuous interferences in defining what these communities stand for and mean, it is hardly probable to articulate the conjoint status of ‘victim’ and ‘predator’. In fact, such victim-predator binaries, in many cases, have been determined by the state where communities sometimes even willingly play their part. However, I congratulate the author, at least, for making that effort in that direction because such discourses might help in future change in the perceived as well as actual performative dimensions and markers of the identities of the communities, which in turn develop a new pedagogy to how we articulate our history and its burdens.