Back to Badaun

ONE MAY DAY in 2014, two teenage girls were found hanging from a mango tree in Uttar Pradesh’s Katra village. Family members last saw the cousins—belonging to the Shakya caste—the previous night before they went to relieve themselves in the nearby fields. They never returned. The discovery of the dead bodies the next day led to speculations of gangrape and murder. Hitting the headlines shortly after Narendra Modi first came to power, this became known as the Badaun case.

It seemed like the same old story wrapped up in a new headline; India was the worst place to be a woman.

Three men, from the more powerful Yadav caste, were initially arrested, along with two policemen. The victims’ family also alleged the police had initially shown little interest in finding the girls when reported missing.

Old caste dynamics became a primary fissure against which to first read the events.

The crime scene also became the heart of a spectacle, the village a staging ground for politicians keen to amass quick capital. The prime minister weighed in. Old statistics on India as a rape capital were dredged up. The story had metastasized from local horror to national tragedy.

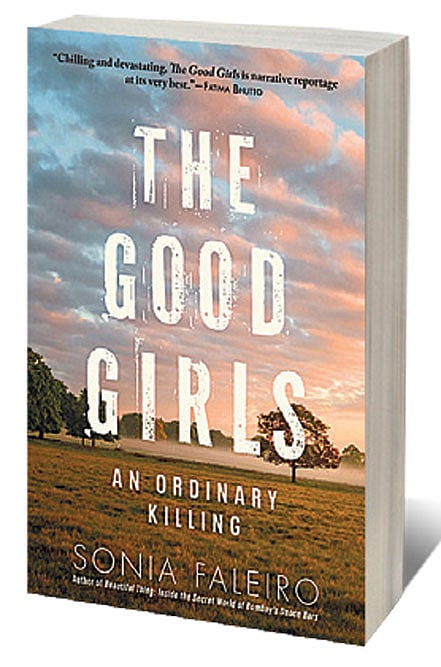

By the time London-based writer and journalist Sonia Faleiro arrived in 2015, the actual events were deep in the past. But the long tail of the aftermath meant that much remained to be unfurled. Faleiro, who previously wrote Beautiful Thing: Inside the Secret World of Bombay’s Dance Bars (2010), on Mumbai’s bar dancers, spent four years working on this book. And it shows. Not a slapdash in-and-out approach, but a careful, deeply reported story drawing in a plethora of voices and from a mountain of documents, The Good Girls: An Ordinary Killing is a feat of narrative reporting. Faleiro expertly reconstructs both the incident itself, and everything that follows; the prevarications, the rumours, the tangle of mistruths and half-truths.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

The result is both a richly damning account of social mores and gender norms as it is of botched police conduct. Here, a former sweeper can conduct an autopsy and valuable evidence can lie unattended for hours.

Gangrape? Possible. Honour killing? Also, possible. At first it seems like familiar ground: the bad old rural north as the epicentre of violence where impoverished social conditions can result in deadly life chances for women. But while this jaded assumption about India seems like the book’s starting point, it unfolds in variegated and unexpected ways.

Perhaps you recall from news reports how the episode unravelled, but I did not. So I won’t say much more.

‘True crime’ as a genre is relatively new to India, but the output has been uneven and few titles have left a mark. In the West though, the category has become tainted by charges of cheap titillation and needless prurience.

Good Girls might be classed as true crime, given the unexplained deaths at the heart of the book. But while it moves with the stealth and speed of a thriller, it is so much more than a

crime story, and by the end, not really what we expected it to be at all.

Sensitivity and close attention mark the storytelling and a determinedness grounds the reporting in ways that distinguish it from some of its lesser genre cousins. Accuracy does not suffer at the hands of pace, nor is ambiguity flattened.

There is one grating tic though. Too often the original Hindi quotes are used, then repeated in an English translation. For instance, we are told more than once of the ‘promise of ‘achhe din’, ‘good days’’. Or formulations such as ‘Bheed kafi hai,’ Ram Vilas muttered… There is quite a crowd.’ Clearly this is meant to appeal to a non-Hindi speaking, probably global audience but the repetition and intermittent tone of Indiasplaining feels jarring at times. Still this is a minor quibble in a remarkable piece of nonfiction.