An Inspired Flight

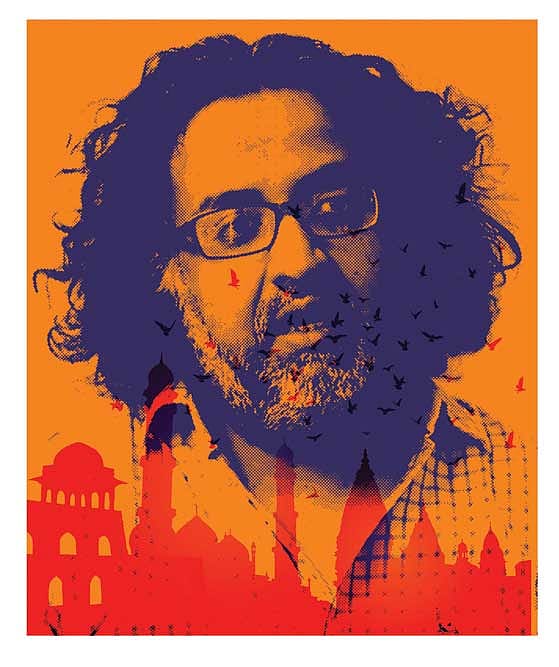

FEW NOVELISTS TRY to write the great Indian novel anymore; it is an unfashionable construct. But in this epic fourth novel, Amitabha Bagchi attempts something approaching it—even as he writes its anti- thesis. Half the Night Is Gone is an extended metaphor, and a prolonged parable; a paean to the old days which brings a furious ambition to bear upon the new ones.

Beginning with the exploits of Mange Ram, who seeks acclaim as a wrestler and falls from the intended heights of his ambitions before they even begin to be realised, in pre-Independence India, the action moves more than a century forward to an epistolary narrative by a sutradhaar of sorts: Vishwanath, a former clerk and Hindi novelist who finds a version of success before realising that his true aim lies far beyond his reach. And, woven into the plight of these two men and their families is the tale of wealthy trader Lala Motichand, son of Lala Nemichand (for whom Mange Ram and his family work) and his two sons, straight-as-an-arrow businessman Dinanath and melancholy thinker Diwanchand, destined to play out the eternal drama of Ram and Lakshman against the more immediate concerns of prosperity and succession, the only goals that matter for families like theirs. A rich panoply, painted in bold strokes— imagine Shamsur Rahman Faruqi and Rohinton Mistry meeting in one frame.

The contemporary narrative is sieved through the lens of empire and time and 80s' nostalgia; the grainy visuals of Doordarshan's Ramayana and the DDA complexes of a life tied to bureaucracy come to mind, reminding us of what a generation of Indians grew up with. The device of Vishwanath's letters , spread over two years, isn't necessarily satisfying, but it is haunting. The older narrative is told with lush, authentic detail, charged with the chicanery and complicated etiquette of courtiers and courtesans. The effect is rich and cloying, but inescapably affecting; its considered language and deliberate rendering come to us as if from a vivid dream.

Rule Americana

16 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 54

Living with Trump's Imperium

Someone else's. And the sensation of partaking of this repast is tremendous, even if, as per Vishwanath—the sutradhaar to whom the author credits the novel that emerges from the world of Mange Ram and Motichand—'language itself hits a limit beyond which it has no claim to the world'. The bigger concern is his repeated question: how can literature impact history? Or, why bother.

The troubled writer and the reader get their answer from questing, suffering Diwanchand—like Vishwanath's brother Jagannath, he has been blamed, unfairly, for his mother's death during childbirth for much of his life, and has escaped to a sublimatory study of Tulsidas' Ramcharitmanas in Varanasi. He explains to a gathering when summoned home after many years: 'To me it appears that Tulsi is saying the route to freedom from the world and its sometimes beautiful and sometimes painful attachments passes through an immersion in those attachments, a wholehearted experiencing of those attachments, and through a continuing struggle to do right by those people and things that we find ourselves attached to, no matter how difficult it is to decide what that right might be.'

Diwanchand's exegeses, pleasurable if ponderous, offer a parallel to the life Vishwanath could have had as a scholar, and his abandonment of his son mirrors the latter's; Bagchi plays skilfully with these two sets of brothers and with Ram and Lakshman, separated by time. For readers, even those who aren't terribly familiar with this era and the great Hindu epics, the connections are wonderful. Though this is of course a requiem, and Bagchi is telling us we can't truly move fluently between the Indian past and present without acknowledging that the former has been misappropriated. Vishwanath writes his novel to punish himself for failing to understand the past. Between the world of 'language' writing and Indian English writing lies a chasm, and he is building a bridge that he knows will soon collapse. Its value lies in its knowledge of its impermanence.

Throughout, like light leaking through the tunnel, is the idea of India. When the writer asks, 'Was the poverty and desperation of our people worse when the British were its cause or is it worse under the rule of us Indians?' he answers his own question, saying that things feel better now, at least; '[I]n 1970, if we look back from the safety of another thirty-eight years, there was no hope left in our nation's life.'

The fog that surrounds us today, even in these improved circumstances, is this book's underlying impetus: this crucial juncture for modern India, looking for answers outside the Congress and the BJP as we know them. 'They could have turned to us for help: Hindi speakers who also believed that not every democracy has to be majoritarian—although I am now beginning to doubt that proposition,' Vishwanath writes. 'At the very least we knew who Tulsidas was and had read his work, which none of them were capable of reading or even understanding if it was read out to them. Perhaps together we could have created an alternate narrative that didn't reduce people's faith to complaints about noisy loudspeakers. But we were always second-class intellectuals to them, never anything more than people who stood and waited, file in hand, while they made the decisions. And what decisions they made!'

Legacy; regret; the fading of ambition; loyalty; piety; duty; the opaque veil of time; personal shortcomings and the curtains one must draw around them (Qurratulain Hyder's River of Fire is quoted to explain the enabling of this action as a noble aim).

This is an ambitious and often earnest novel. Bagchi's humorous IIT Delhi tale (the best-selling Above Average) and novels set in Baltimore (This Place) and Delhi (The Householder) have earned him a reputation for his acute eye. And there is considerable wisdom in Half the Night, an invaluable intuition of the back-and- forth of the examined life—as well as wit. Between gorgeous passages wherein scripture extends to life and lights it up, Vishwanath observes of his father's employer, for example: 'There was goodness in him, just not the kind of goodness I was looking for.'

However, the story is uneven at times. The widow Kamala, a fascinating woman who falls in love with Diwanchand, is forgotten, and other minor characters, mostly mothers and sisters, fall away—while the novel's other interesting women, powerful yet restless Suvarnalata, and Sahdeyi, power player and mistress, get more space. This may have been typical of pre-Independence times, but Vishwanath's wife Vimla, too, is relegated to dutiful object. Even if the novel is at one level a portrait of the pervasive privilege of the Indian man in pre-Independence and independent India, it can get tiresome to have the message drilled in at the expense of some singular characters.

Yet, Half the Night is redeemed by the rare and uplifting skill the author employs to attempt this inspired flight. Diwanchand tells us, 'there is a proximity to that perfect utterance that takes us as close to a knowledge of the unknowable that mortals like us can hope to achieve'; hence the value of the form, and the inevitable constraints.

This is a novel which dwells upon the long reflection before the big event; 'by the time half the night was gone' Diwanchand makes a momentous decision that changes the course of many lives. And so, to the long night that awaits us, Bagchi's Vishwanath quotes these lines from Dushyant Kumar: 'sirf hangama khada karna mera maqsad nahin hai/ meri koshish hai ki ye soorat badalni chahiye —It isn't my aim just to make a racket/ My aim is that things should change'.

Hail Bagchi's valiant foray, and read this moving novel. It is a piercing flower in the desert that is Indian literary fiction in English this year.