Amol Palekar: India’s Everyman

“SO, THE BOY NEXT DOOR was a giant con, was it?” I ask Amol Palekar, to whom this descriptor was attached throughout his career in Hindi cinema. He smiles mischievously, with the beguiling innocence that marked all his interactions in Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s Gol Maal (1979) with the late great Utpal Dutt. And launches with relish into a monologue explaining why he resisted being put into the box Mumbai cinema wanted him to be after three successive hits as the typical middle-class man in Rajnigandha (1974), Chhoti si Baat (1976) and Chitchor (1976). “In Bhumika (1977), I was an abusive husband; in Gharaonda (1977), I wanted my girlfriend to marry a rich old man because I wanted a house, and in Khamosh (1986), I played a murderer, a particularly sinister one,” he says with a laugh, chronicling just some of his nasty, toxic men he’s played in his career. He’s not finished. “And even when I played the so-called boy next door, I never told the women that I loved them. But I think what worked in each of these characters was their vulnerability,” he chuckles.

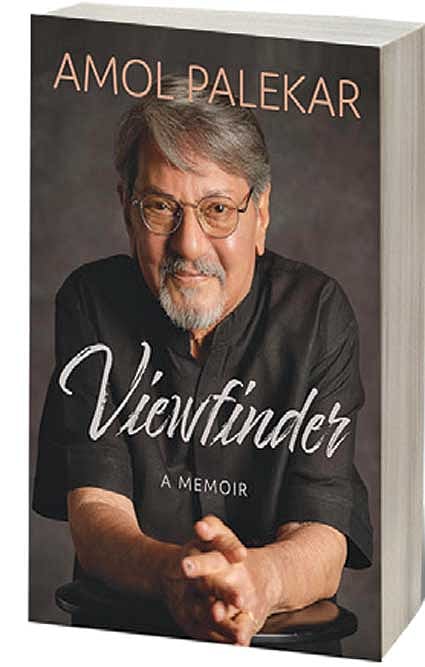

At 80, Palekar has a rich body of work to reflect upon and he does so in an elegant memoir, Viewfinder (Westland; 320 pages; ₹999). An accidental actor, he was a bank clerk who was asked by theatre guru Satyadev Dubey to start attending rehearsals because he would hang around his then girlfriend and former wife Chitra Palekar. He went on as he had begun, with his feet firmly planted on the ground and his head on his shoulders. From Marathi theatre, he became a staple of Basu Chatterjee’s homely cinema of the 1970s, before graduating to directing his own movies, many of which were groundbreaking for their examination of female pleasure and alternative sexuality.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

His trilogy of taboo-breaking movies began in 1996 with Daayraa, the story of a crossdressing man, and a woman who chooses to dress as a man. The second in his trilogy was Anaahat (2003), where a queen is made to sleep with another man in order to produce an heir for her husband only to discover that she likes the joy sex brings. It was shot in Hampi, a world heritage site, and starred Sonali Bendre, who till then had been playing doll-like roles in mainstream Hindi cinema. The third, Thang, which came as late as 2006, was about a woman who discovers her husband is in love with another man. Palekar ascribes his understanding of feminist themes to the strong women in his life, beginning with his mother, his first wife, his daughter and his beloved second wife and his backbone, Sandhya Gokhale. “The women in my life shaped me so well. So many women gave me the love my mother never did, and I am glad I evolved and grew out of my male chauvinist attitudes. It was quite inevitable that the women in my films would be very strong. It started with Ankahee (1985) itself. I wanted to change it from the play to the film adaptation. I am glad Sushma who commits suicide in the film says it is not suicide but her refusal to accept the roles ascribed to her. It was the starting point of my exploration of women and their sexuality,” he adds.

He describes Gokhale, who has been with him for 25 years, as the woman holding him afloat in the vast ocean of life. Indeed, Gokhale, a former lawyer, and now an acclaimed writer, has been the guiding force behind his memoir, which he wrote by hand in Marathi. She translated it from Marathi to English, and came up with the idea of enabling access to several of Palekar’s movies and photographs through QR codes. It is an unusual but necessary way to build our rapidly disintegrating cultural legacy.

Palekar was a reluctant star, often confounding producers who really wanted him to continue delighting audiences with his Everyman in Search of Every Basic Need, from a home, to a job, to a wife. Sometimes he was Ramprasad Dasrath Prasad Sharma in search of a job and ready to do anything for it, even wear a fake moustache as in Gol Maal. At other times he was Arun Pradeep in search of a way to talk to the girl of his dreams in Chhoti si Baat. At yet other times, he played a husband, Bhagwant Kumar Bhartendu, looking for another husband for his wife in Meri Biwi ki Shaadi (1979). “When I chose to do Bhumika,” he says, “the industry was shaken. It was immediately after three silver jubilee hits. But the artist in me was more excited to play the black character than Mr Goody Two Shoes. And even when I played villains I did so differently, not by raising an eyebrow, twirling my moustache, uttering some dramatic dialogue and fighting 20 guys, but silently, creepily.” He gives the example of Khamosh where he says director Vidhu Vinod Chopra accepted his suggestion of playing the killer like a cat preying upon a mouse rather than a tiger roaring to scare the hunted. “I was fascinated by the idea of playing a villain like a cat and mouse game,” he says.

Yet he turned his back on mainstream Mumbai cinema, despite the advice of friends such as Shashi Kapoor. He even took on filmmaker BR Chopra, suing him for unpaid dues. That has been Palekar’s hallmark. As much as he is a painter, an actor, a director, he is a citizen first. He fights for freedoms big and small, even if it is only a green space near his home in Pune. The memoir, in fact, is dedicated to “those who believe in the power of resistance”.

The book is a stock-taking by a man who has always been self-effacing, who has believed in challenging himself. He asks in the memoir: “What do I do with the trivial, scattered details? Like the first time a shirt stitched at Tardeo’s Kachins touched my skin, the affection that overwhelmed me as I wiped the drool off my exhausted dog Junior’s mouth, the twist in my gut as I packed the first canvas bought by the Tata Group.”

There is a sense of mortality that pervades the memoir, and I ask him about it. Is death so depressing? He looks surprised. A good death is something we should all welcome, he says. He has challenged death for some time, smoking 72 cigarettes a day for 40 years. His lungs, his doctor once told him, are that of a 136-year-old man.

There is an annihilation of the ego that allows him to speak about others with more fondness than he does about himself. When I remind him of how at one point his onscreen association with Utpal Dutt was considered the best romantic pairing at the time, he asks whether I know that Dutt was the first artist in free India to be arrested for sedition for his article Another Side of the Struggle in Deshhitaishee and spent seven months in prison under the Preventive Detention Act 1965. What was the magic of their relationship onscreen? Palekar says it was because they knew each other from theatre and the man he knew was very different from his film portrayals. He says, “Whenever I was shooting in Kolkata I would rush to his rehearsals after pack-up. We knew the entire making of Gol Maal was fun, holding hands with each other, helping each other, no competition between anyone. All of us were like a family and we would enjoy our work.”

Mention Dubey and he speaks about his tough love. Talk about his mother and how he forgave her in her death and his eyes still well up when he speaks of how she never accepted his first wife. “She never held me close, ruffled my hair. In her last days she stayed with me and there was a tremendous change in her, but it was too late. Before she died, I wanted to tell her how much she had hurt me but I never did,” he says.

This is a man who has lived on his own terms, not always doing the popular thing. It has, however, always been the correct thing, whether it is accepting his daughter’s choice of sexuality or standing up to censorship. Pre-censorship of plays, required only in Gujarat and Maharashtra, continues to worry him. The same play, he says, could be performed in other states without any vetting. Why are artists alone subjected to pre-censorship? “While addressing mammoth rallies, politicians can say whatever is imaginable. Why don’t they have to pre-submit their speech? Why are they not asked? Certain words in their speech are too explosive and must not be said in public, no, he asks.” The Supreme Court recently decided to examine his seven-year-old plea questioning pre-censorship in cinema.

There are many small and big acts of rebellion in his life. Palekar has effectively been an outsider in mainstream Mumbai cinema despite delivering some of the most memorable hits of the 1970s. He has also been an outsider in what was called the parallel cinema movement, because he was not trained either at the National School of Drama or at the Film and Television Institute of India. Yet, as he writes, “despite being surrounded by negativity, I managed to find serenity within myself. I won’t deny that it disturbed me to see the way others around me landed new roles. This repulsion led me to make poor personal decisions that did not serve me well. I often internalised the anger I felt towards others and directed it inwards.”

Palekar has seen the birth of transformative technologies, the replacement of the heavy Mitchell with the Arriflex camera which got filmmakers to shoot outdoors but also got them to dub the dialogues because of the sound. Palekar was a different kind of actor from those today—he had no manager, no hangers on, no publicist to counter film magazine gossip. He was a different kind of director as well—investing his own money to make the film he wanted to.

He calls himself a limbu-timbu (Marathi slang for a small lemon shrub) compared to the greats whose conversations he has witnessed and whose lives he has been part of, from Mohan Rakesh to Dubey. But that limbu-timbu has become a sheltering tree, giving succour and shade to many in search of inspiration in these challenging times. He is ready for death now, he says. “Every film has to have an end. It’s a simple fact of life. It is not depressing, the whole journey has been so beautiful, enriching and joyous. I went on growing up and the people whom I met gave me in abundance and made me who I am. Most of them are not there anymore. I am thinking of the party we will have up there. I am looking forward to it.”