Amit Majmudar: ‘There Are No Atheists in the Trenches’

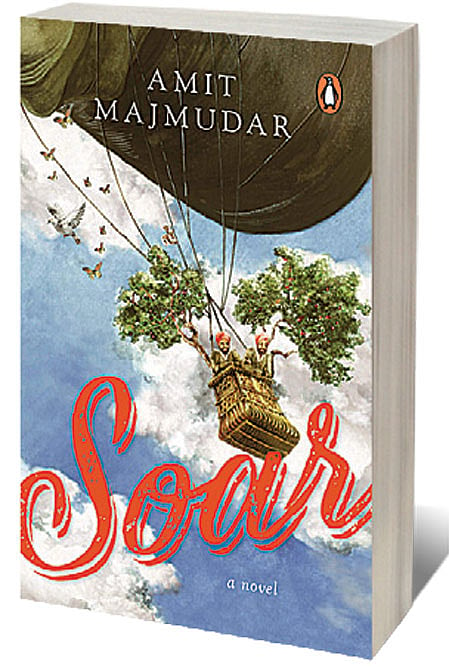

AMIT MAJMUDAR’S latest offering, Soar (Viking; 147 pages; Rs 399), is a tragicomic story of a friendship between a Hindu soldier and a Muslim soldier who fought for the British in Europe during the First World War. Majmudar, who hails from a Hindu family, says he rarely discussed religion with his childhood friends—the conversation was dominated by Transformers and video games back then. “The sentiment of friendship overcoming background is very natural to me,” he says, “Growing up, my earliest best friends were Christian and came from fairly devout families [they were all coincidentally named Nick].” Even in the present, his closest friends include a staunch atheist (from an originally Christian family) and a non-practising Hindu. Soar has partly emerged from the fact that he never learnt to divide interpersonal relationships according to religion.

Majmudar, a novelist, poet, translator, essayist and diagnostic nuclear radiologist, is best known for his 2018 book Godsong: A Verse Translation of the Bhagavad-Gita with Commentary and the mythological 2019 novel Sitayana. Soar is altogether different. It follows two Gujarati soldiers, Bholanath and Khudabaksh, who have been dispatched to fight the allied powers in Europe. The pair, who cannot be relied on for much in perilous circumstances, is fired from various tasks till they are finally assigned to fly a hot-air balloon to carry out reconnaissance on enemy movements. The contraption is tethered by ropes to the ground where a harrowed Colonel Mountjoy attempts to supervise the dubiously equipped duo. The novel’s real adventure takes off soon after when a mishap involving a tenacious squirrel severs the link between the ballooners and the base team, and Bholanath and Khudabaksh are set adrift in the skies above Europe with only each other and a stowaway squirrel for counsel, comfort and commiseration.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

By some estimates, 40 per cent of Indian soldiers serving in the British army were Muslim, which would have created increased opportunity for interfaith friendships like the one portrayed in the novel. In 2017, the Forgotten Heroes 14-19 Foundation in the UK shed light on the crucial contribution of Muslim soldiers in the making of modern Europe. These soldiers shared folk songs and herbal remedies with their comrades across lines of race, nationality, language and faith. Bholanath and Khudabaksh are a light-hearted manifestation of a reality that is underreported. The religions of the men in the trenches were strengthening and galvanising forces, as are for the two heroes who use these to process inexplicable events—in some ways, the absurdness of a hot-air balloon mission draws attention to the senselessness of the carnage.

Based in Westerville, Ohio, Majmudar has been a WWI buff for years. When asked about the importance of religion in a war story, he brings up a famous saying that is believed to have been coined during WWI: “There are no atheists in the trenches.” He recalls the extant photographs of priests in white robes offering blessings to regiments before they entered the trenches or charged into machine-gun fire. Since time immemorial, he says, religion has quelled, to varying degrees, the terror of death.

In 2010, Majmudar had just finished writing a very different odyssey—his first novel, Partitions (2011), which followed Sikh, Muslim and Hindu characters in the forced, bloody migration of 1947. Immediately after completing that novel, he worked on this diametrically opposite project—an exercise which was partly an attempt to test his creative range and partly a desire for a change of mood from the harrowing darkness of Partitions. The reader’s first exposure to the story’s levitous approach is in Soar’s chapter titles such as ‘Good-For-Nothings’, ‘In Search of the Balloon’ and ‘Some Serious Cheering Up’. He chose humour as a vehicle for a narrative about war and suffering because he believes that levity can sometimes reveal aspects of reality that seriousness cannot. He explains, “Life contains both elements, often together or closely juxtaposed, as in a Shakespeare play. Many books try to stay entirely lighthearted or entirely dark, but that is not reality.” The blend of horror and amusement, comic camaraderie and necessary interdependence in his novel stems from the sense that “pure seriousness cannot reveal the fundamentally mixed nature of human experience”.

Traditional odysseys will often feature heroes with exceptional intelligence, grit or skill that will determine the course of a larger narrative, but the comedic heroes of Soar are footsoldiers who have only their ordinary selves to offer and who will change little except as part of their squadron. Pointing out that comic journeys such as Don Quixote have always existed, Majmudar says he chose protagonists who are “slightly simple and rather bewildered by the warfare and hatred they encounter in this European hellscape” to achieve a “poignant and sweet” effect.

Bholanath and Khudabaksh share Majmudar’s Gujarati roots which he says allowed him “to imagine these two soldiers as lovingly as I would my own grandfathers—both of whom passed away before I was born. Perhaps some parts of this book were an attempt to imagine my way into their company?” There were no stories of military service in his family, so he made the adventures himself out of whole cloth. The two men display racial and gender prejudices that are startling to encounter as a contemporary reader. Majmudar developed the men’s belief systems by focusing on making sure their words and thoughts were consistent with their personalities. In his experience, he says there is “a certain imaginative ‘rightness’ to things a novel’s character can say and do, and that ‘rightness’ transmits to, and is perceived by, the reader. It is not easy to define how that works. It is partly a matter of preventing anachronism from creeping in, or preventing a contemporary ideology from turning your historical characters into mouthpieces”.

There are several non-human characters in the novel—pigeons, horses, a squirrel and so on—that suggest that the costs of the war extended far beyond the human realm. They also provide respite from the suffocating violence and loneliness within the story. Majmudar sees the novel as possessing a magical realist element and the quality of a fable. He says, “Towards the end [spoiler alert], the novel leaves hints that the entire story as told is a dying hallucination or dream. So that dreamlike quality is brought out when the animals show anthropomorphic qualities. They don’t talk in the manner of an Aesopic fable, but the soldiers do talk to them, and believe that the animals can be communicated with.”

Soar remained on the author’s hard drive for eight years before he found an Indian publisher to whom he showed the manuscript. The novel is out in print at a time Delhi is rebuilding after riots that claimed 53 lives (officially) and destroyed private properties and businesses. “I have studied a lot about the religion and history [and the history of the religions] of India. I am very interested in the differences between group interactions and individual interactions: how a mob of people can commit an act of violence, in public with the anonymity of numbers, that a single individual would not feel capable of doing even in private,” he says. He sees it is as a curious fact about human beings and conscience that, in some instances, individual morality does not always ‘scale up’ to mob or group morality.

His book, Godsong, was an adaptation of the Bhagvad Gita in verse—at the time, he saw the Gita as an antidote to rising fanaticism. Now, he hopes that a tragicomic novel of friendship between a Hindu and a Muslim, facing a common horror in the First World War, can show the way to reconciliation and healing. It strikes him that individual, interfaith friendship is the crucial element that can prevent a person from participating in group hate or group violence. He cautions, “Mutual insulation correlates with suspicion, hatred, anger. If you have even a single true friend from a different religious community, there is an instant revulsion against generalisations that malign that community”.