Aanchal Malhotra: The Memory Keeper

FOR AANCHAL MALHOTRA, ‘1947’ had never been just a year or a subject confined to textbooks. All four of the 32-year-old writer’s grandparents moved to Delhi from various parts of what would become Pakistan. Her paternal grandfather Balraj Bahri founded Delhi’s iconic Bahrisons bookstore at Khan Market, then a newly minted commercial initiative to help Partition refugees. Two objects that Malhotra’s maternal grandfather’s family carried over from Lahore—a simple vessel (used by her great-grandmother to churn milk) and a yardstick (used by her great-grandfather, who had a clothing store)—sparked her interest in collecting both oral histories and “material memories”; heirlooms, antiquities and other objects (mundane or ornate) that connect people to their family histories. Malhotra’s first book, Remnants of a Separation: A History of the Partition through Material Memory (2017) began life as her MFA thesis and in its finished form, was shortlisted for several awards including the Shakti Bhatt First Book Award and the Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay NIF Book Prize.

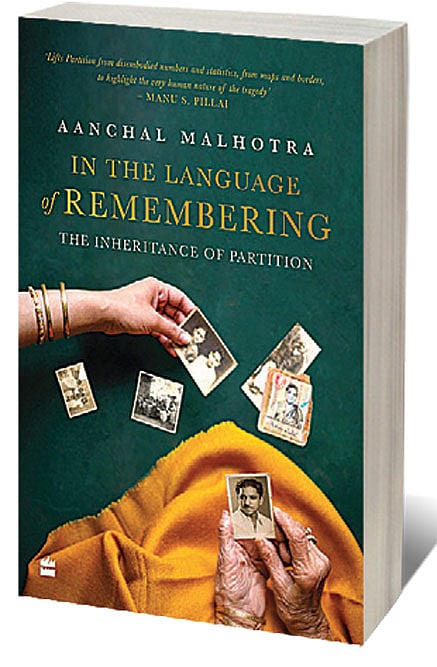

Recently, her second book—In the Language of Remembering: The Inheritance of Partition (HarperCollins; 756 pages; ₹ 799), a collection of thematic essays on both Partitions (1947 and then 1971, the birth of Bangladesh)—came to life. Broadly speaking, the book maps the seemingly infinite ways in which the Partition—and in a lot of cases, the ensuing migration—continue to affect the lives of survivors as well as their families. The bedrock of the book is the treasure trove of interviews and testimonies Malhotra has gathered, as oral histories from across India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, and these demand slow and careful reading. The chapters are thematic, each named after one guiding word or emotion: ‘Family’, ‘Grief’, ‘Friendship’, ‘Hope’ and so on.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

During a telephonic interview, Delhi-based Malhotra spoke about the sensitive nature of these interviews and how it can be tricky getting people to open up about generational trauma. “Obviously, you can’t make someone talk, to begin with,” Malhotra says. “And if they want to be anonymous you have to respect that as well. But in most cases, I found that if people wanted to talk, they’d do so in a very open and comfortable manner. When someone’s having these conversations with you, they’re also making those associations at the same time— connections with their ancestors, with their memories and yours and what these connections mean for them now, today, in their everyday lives.” She adds that everybody had their own pace and rhythm of opening up; some would open up in the very first conversation while for others it could be a conversation followed by several emails and phone calls.

There is a temptation, especially among narrative historians and journalists, to make somewhat tenuous connections between the events of 1947 or 1971, and contemporary acts of political violence across India. In this reading, history becomes a kind of explanatory arithmetic for events that we’re living through today—no more and no less. Malhotra’s work in both Remnants of a Separation and In the Language of Remembering is astute because it recognises the folly of this approach. These books treat history as the multi-modal entity that it is, not as a flat, linear, cause-and-effect phenomenon.

“It is dangerous to always draw a straight line between acts of communal violence that happen today and the events of the Partition,” Malhotra says. “But of course, there are some things that are certainly connected. For example, you can draw a straight line between 1947 and 1971. I think some of the most striking conversations I had while writing this book were those in which I realised, for example, how the events of 1971 are perceived so differently by the people of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh.” In one of the most surprising conversations she had during the writing of In the Language of Remembering, a Pakistani-origin woman in her 30s mentioned that her parents met during “the Partition”.

Malhotra expressed surprise — how could this young woman’s parents have been alive during 1947? She then realised that her interviewee was talking about 1971; for a Pakistani family, it would be called “Partition” whereas for Malhotra it was “the Third Indo-Pak war”. “I then started thinking what else she had said during our conversation that I had interpreted in an entirely different way!”

When Malhotra was 17, she moved out of Delhi and did her BFA and MFA (she’s a printmaker by training) at Toronto and Montreal, respectively. While at university in Canada, she found that Indian and Pakistani-origin students were comfortable in each other’s presence and bonded over the considerable common ground they shared, culturally speaking. Of course, the fact that they were both minorities in a white-dominated place also helped.

“It’s like a paradox, right?” Malhotra says. “When we are in India and Pakistan, we are far more territorial. But when we’re not, we tend to be more receptive and appreciative of things like somebody speaking Punjabi in a way similar to us, or wearing clothes or eating food that’s similar to us. When I was a teenager in Canada and I met Pakistani-origin students I immediately felt that connection.” She adds, “I don’t know if people want to hear this or not but at least with north Indians there’s something innate that binds us to Pakistanis, in terms of a seamless transference of cultural, familial habits. In a place where so many North Americans exoticised us, othered us, I really felt at home with people from ‘the other side’. And I was hardly the only one who felt this way.”

In the penultimate chapter of In the Language of Remembering, called ‘The Other’, there’s a moving, lyrical description of Malhotra’s experiences at university, where she bonded with Pakistani students. It’s indicative of both her style as a writer and the irresistible, irrepressible humanity of the archival project she’s devoted the better part of a decade to.

“When I was shown photographs of the Badshahi Mosque [in Lahore], I reciprocated with descriptions of the Jama Masjid. In the sub-zero Canadian winters, when they would describe the salty air at Clifton Beach, I would add my memories of Marine Drive. Together, we would dream about the intoxicating smell of rain and the warmth of a subcontinental sun. We would collectively despair at the sweetness of the butter-chicken gravy in Canadian restaurants, and participate in ‘desi’ festivities at university, regardless of whether it was Diwali, Eid, Holi or Garba nights. I don’t remember feeling that their Pakistani identity diminished my Indian one, or hindered my understanding of them, and vice versa.”

Of course, as one expects with a communally charged topic like Partition, Malhotra has had to deal with a fair amount of pushback during the course of her research. People calling her “Pakistani” or “spy” was commonplace (conversely, her Pakistani oral historian counterparts were pelted by their compatriots with accusations of cosying up to India-the-enemy).

Malhotra is also a novelist—her first novel The Book of Everlasting Things is expected later this year from Harper Collins India. Her fiction also involves Partition, and also the largely neglected role of Indian soldiers in the First World War. As a writer and a bookseller, Malhotra has considerable knowledge and understanding of the way Partition novels and poems have changed down the years. “If you look at the early Partition novels to come out of the Indian subcontinent,” Malhotra says, “Whether it’s Krishna Sobti or Bhisham Sahni or Yashpal or Amrita Pritam, these were written by people who had actually lived through the Partition, so they have that immediacy, that urgency in them that comes from lived reality. To that extent I would put them alongside the oral history work being done today. If you look at some of the great Partition novels of today, say Tomb of Sand by Geetanjali Shree, that’s the kind of book that can only be written once you have that distance of 30,40,50 years from the things that you are writing about.”

The Hindi novel Malhotra refers to, Ret-Samadhi or Tomb of Sand (translated into English by Daisy Rockwell), has recently been shortlisted for the Man Booker International Prize and involves an octogenarian woman’s hidden past in Pakistan, where she insists on returning in order to retrace her roots. The general awareness levels and historical literacy of people (or the lack thereof) from both sides of the border is a recurring theme in Tomb of Sand; hence Malhotra’s comment about this being a novel that could not have been written in the 1950s and 60s, when the wounds were still fresh, so to speak.

“In some ways even the work that myself and others are doing today, in terms of oral history, is only possible because we have that distance of many decades,” says Malhotra. “For so many people, silence around these things felt like a betrayal as I’ve written in this book. But there were also a large number of people who just did not feel like speaking about it until now. There were many reasons: it could be trauma, it could be for lack of listeners, or just the fact that nobody had asked them these things seriously, and with documentation or academic work in mind.”

Towards the beginning of In the Language of Remembering, Malhotra cites the work of Marianne Hirsch, who coined the term “postmemory” to describe the unique lived realities of Holocaust survivors, and how they relived the tragedy in their daily lives, the kind of impact this had on their psyches. She also notes that there is no comparable term or phrase to describe the experiences of Partition survivors (and it’s not fair to transpose the same neologism in this context too).

It’s fair to say that her own books, especially In the Language of Remembering with its broad area of focus, are important contributions in this context. This is not narrative history in the traditional sense—Malhotra is clear about the fact that this is a collection of essays—but the narrative that gently unfurls itself across these 750-odd pages adds up to a kind of history, that too at an unhurried pace, to be consumed on its own terms. If you’re fatigued by reading run-of-the-mill history books on the subcontinent’s many Partitions, In the Language of Remembering will surprise, educate and enthral you.