A Matter of Taste

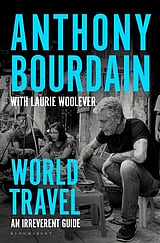

In this horrible pandemic, we are missing out on many things integral to human existence. Among the less obvious are travel, being exposed to new experiences, engaging with strangers, and eavesdropping on conversations. Anthony Bourdain’s World Travel: An Irreverent Guide (Bloomsbury; 480 pages; Rs699), posthumously put together by Laurie Woolever, gives us a taste of these elements that make up our experience of travel.

The book is not written by him—he committed suicide in June 2018—but is based on discussions he had with Laurie Woolever when they were planning it. It also contains tributes by his brother, his production manager, and his music producer. If you are expecting a travel guide, this book isn’t for you. But if you want to glimpse 43 cities through Bourdain’s eyes, get it. What his legion of fans responded to was his ability to tell it as he saw it, but in a charming way, innocent of malice.

It has his trademark caustic asides. “Sardinia’s the kind of place you better know somebody.” Or this one on Punjab. “Checking off my list of things to do in the Punjab, I gotta score some animal protein. It’s time. I’ve been going all Morrissey for like two days now, and frankly, that’s enough. I need chicken. When we are talking Punjab must-haves, tandoori chicken is just that.”

Underlying these non-politically correct observations is the affection one feels for a sibling whom one may not understand but nevertheless one cares for. A card-carrying carnivore, he finds the thali meal a thing of wonder in Natraj (Udaipur) that makes “veg-only fare vibrant, flavourful and fun.”

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

The anecdotes capture his cartoonist’s ability to highlight the idiosyncratic features of a place—the smells, the feel, the look. He helps a global audience understand the flavour of a strange-sounding local dish by highlighting the similarities. In Khau Galli, Mumbai, he gorges on beida roti, “kind of like an Egg McMuffin, only good: mincemeat and eggs fried up in chapati.”

For those of us who miss him, World Travel brings back a sprinkling of his acerbic wit and entertaining anecdotes.

The Flavor Equation:The Science of Great Cooking Explained in More than 100 Essential Recipes by Nik Sharma (Harper Collins; 352 pages; Rs 1999)

These days I just want to eat someone else’s cooking. So when The Flavor Equation landed on my table, my first thought was, ‘Oh no, not another book of recipes that needs hard-to-get-ingredients, has to be cooked or baked for hours in a hot kitchen (made hotter by our summer) and ends up producing a bland (to the Indian palate) dish.’ To my pleasant surprise, the book is a nice mix of easy science and quick tips (the first 70 pages), followed by easy recipes using accessible ingredients—paneer, chickpeas, eggs, amchur powder, tamarind paste—all of which you can get at the kirana store.

Nik Sharma, whose father is from north India and mother is from Goa, grew up in Bombay and moved to the US. The Flavor Equation, despite its science-geek name, thankfully places more emphasis on emotions and memories. Flavour, he says, is made up of many parts. One part is driven by our emotions and memories, while the other part we decipher using our senses, sight, sound, mouthfeel (texture), aroma and taste. For instance, he talks about making sweet hot tea infused with ginger and cardamom for his parents ‘to soften their reaction to whatever I’d done wrong that day.’

“Think of ...a caprese. You pick out tomatoes based on their vibrant colors and shapes and their wonderful aroma. You slice through the tomato and feel the flesh give way under the sharp edge of the knife. Now in goes the large ball of creamy, smooth mozzarella, a sprinkle of crunchy salt and cracked fresh black pepper, a splash of sweet-sour balsamic vinegar and borderline-pungent olive oil....Your senses are in overdrive, guiding you along the way as you cook, and then come into play once again when you take a bite. You taste salty, sweet, sour, savory, along with the fresh aroma of herbs and the luxurious nature of fat.”

As you can see, his style is easy and conversational, yet redolent with evocative imagery that makes the reader see, smell and taste the dishes he describes.

Another element that makes the book stand out in an overcrowded cookbook marketplace is how scientific information is doled out. Nik uses stories from his childhood to illustrate the science underlying a habit. For instance, asafoetida contains a chemical (dimethyl trisulfide) and other sulphur-containing substances present in alliums such as garlic and onions. His widowed paternal grandmother, he says, gave up eating onions and garlic because they might induce impure thoughts. She began using asafoetida in her cooking. A similar story can be told about some groups in South India who use asafoetida in dishes and refrain from using onions and garlic. It made me realise why asafoetida is ubiquitous in those cuisines. Or why vegan cooks use kala namak—because its sulphurous smell creates an ‘eggy’ aroma.

The recipes unusually blend Indian tastes with non-Indian recipes. Tamarind, gunpowder, turmeric, pomegranate molasses, and buttermilk are in recipes like gunpowder oven fries with goat cheese dip, roasted butternut squash and pomegranate molasses soup, pomegranate and poppy seed wings, roasted tomato and tamarind soup. In a shepherd’s pie, he uses kheema and chorizo. A burnt kachumber salad goes with a coffee-spiced steak.

To achieve a twist to classic flavours, one has to be very careful. The only principle is you can change anything in a dish as long as the result is better than the original. Very hard to do but in several recipes mentioned above, Nik manages it. And where the classic is perfect—like Dal Makhani—he doesn’t tweak it. That’s also important—to know when the flavour is perfect.

Spiced, Smoked, Pickled, Preserved: Recipes and Reminiscences from India’s Eastern Hills by Indranee Ghosh (Hachette; 248 pages; Rs555)

The title of Shillong-born Ghosh’s book is self-explanatory and focuses on a less-well known cuisine. While Ghosh too connects flavours with memories and emotions, her stories have a wonderful layer of history lived by three generations of her family.

The introduction is a lovely memoir of growing up in the Khasi and Jaintia Hills, and spans three generations from the early 20th century to early 1970s. The family cooking, she says, was a reinvention of what belonged to three regions: West Bengal, East Bengal, now Bangladesh, and Shillong. For her, the differences in the cuisines were between the hills and the plains; vegetables grown in the hills are different from those in the plains. Watercress in the hills, for instance, is not kolmi, the watercress found in West Bengal plains. Hill watercress is crunchy and rich in blood building nutrients.

Another difference is that parboiled rice eaten in the western plains doesn’t feature in the hill diet. Items we may see as intoxicants, are everyday fare for some. “Cannabis seeds make a delicious Nepali chutney, ground with roasted black sesame, dried chilli, tamarind and salt.” Other unusual foods found in the hills are edible insects such as the silkworm, the lobworm and the wood beetle (which look like peanuts, and can be roasted and the inside sucked up like oysters with a bit of lemon or chomped whole like peanuts).

The book’s organising principle too differs from Nik Sharma’s book. It begins with stories of her large multi-generational family including eccentric characters and their recipes(section I), then moves to the kitchen where the vessels, herbs and vegetables special to Bengali cuisine are discussed (section II). Finally, the recipes in Section III follow the courses in a Bengali meal. The second section discusses vegetables considered delicacies in Bengali cuisine. These include ripe and unripe jackfruit, banana flower, onion shoots, teasel gourd, bitter gourd and watercress. It helps us understand the taste-profile of the recipes in section III.

The sequence of a Bengali lunch is different from the south Indian one (which has spicy, savoury, sweet, then bland). Here, it begins with bitter, bland, savoury, spicy, sour and ends with sweet.

Shukto, bitter stew, was the starter, and in the recipe for kancha peper shukto (green papaya shukto), roasted and ground fenugreek seeds add the hint of bitterness. It sounds delicious: slice papaya, boil with a little water, milk, salt, sugar and ginger paste for ten minutes until the papaya is almost cooked. Then in a kadhai, melt ghee, add fenugreek seeds, dried chilli and bay leaves, let it sputter and brown, then add the papaya mix and roasted fenugreek, and cook well for three minutes. The bland tastes are carried by the saags made of spinach or watercress or bottle gourd. Savoury, spicy, and sour comes from the preparations for dals, vegetables, eggs, meats, and fish.

Some of the dal recipes are different from the style used in other parts of India. For instance, in masoor dal chochchori, red lentils are fried with bay leaves, cinnamon, and cloves along with the onions, chillies and ginger, and then boiled.

Most recipes for vegetables use mustard oil. The spice comes by adding dried chillies and green chillies. Another interesting recipe is cabbage with pepper and milk. In the south we use coconut, not milk. The taste is not dissimilar though, and the milk softens the cabbage.

Eggs are cooked in different ways, and their flavouring is similar to other parts of India—ginger, green chillies, tomato, and sometimes cloves and cinnamon as in the fried egg curry. I tried the egg steamed in mustard sauce, which was simply delicious (and quick to make).

The meat recipes are applicable to chicken too, and require a longer presence in the kitchen if slow roasted. For those in a hurry, Ghosh includes the pressure cooker option and most important, the time measurement. Fish, of course, features prominently, and is followed by khichuri (rice with lentils) recipes include festive ones (bhaja moong dal khichuri), convalescent fare, and healthy options (daliya khichuri).

The desserts have some unusual variations. Coconut payesh (similar to payasam or kheer) has coconut, date jaggery, milk, raisins and roasted peanuts; a tangerine payesh, which when made, was tart and sweet. I am looking forward to trying out more recipes after summer. A thoroughly enjoyable book to read and taste.