No One Wants to be Like India

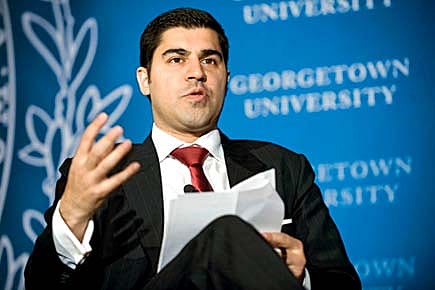

Parag Khanna has always been on the go. Open's David Lepeska recently corralled him for a wide-ranging discussion. Excerpts

Q You've said "India will never rival China" but to what extent can India claw its way back, close the gap in the next 20, 30 years?

A Will the Indian economy grow to rival China's? Not any time soon. Right now it's 1.5 per cent compared to China's 16 per cent of the global economy, $1 or $2 trillion FDI per year compared to a couple hundred billion. Indians always say, 'Well, give us 10 years, 15 years…' Oh right, so China is going to freeze in time so you can catch up? No, everything is always in motion.

Q What about the oft-cited Indian advantages of democracy and an ability to innovate—don't those count for something?

A No, on both counts. We underestimate the Chinese because we believe all they are is rote copycats. But they're investing in innovation. About democracy, I have two words on that: one is Burma, the other is Tibet. These are examples of India throwing democracy out the window for natural gas and territorial security. At the end of the day, the question is: who do you want to be like? People talk about a 'China model' all over the world today; a lot of people want to be like China, but no one wants to be like India. Not yet anyway. In my next book, I write about the 'Indian model'. It's a model of public-private governance, like the relationship between the Planning Commission and the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII). It's like this [raising two entwined fingers], and that's been one of the best things that ever happened to India…

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

Q What does the decline of national political parties mean for India and its democracy?

A This whole national party versus regional party thing is part of what I call post-colonial entropy, which is a very fancy way of saying that the elements of central administrative authority that existed in the colonial era are gradually decaying along multiple lines. Pakistan is the world's most acute example of it, but there is evidence that it exists in India as well. You have a resurgence of caste-based, ethnic, geographic and linguistic identities.

Q Good or bad for India?

A There's a good and a bad side to the fragmentation of Indian politics. The good side is that it encourages a kind of healthy competition, and a sense that people have a stake in something, if not in the Centre at least in their own area…. But what this exposes is that this hereditary dynasticism has to die. Even if the Congress does win by these razor-thin margins, it doesn't mean they're vindicated. The trend is still clear. If you want to differentiate yourself from Pakistan, you can't be a Bhutto- and Sharif-like country, especially since we've had land reform in India and Pakistan hasn't. Why the hell can we not graduate beyond the Gandhis? I want to see a meritocratic India otherwise the government will never have the respect the private sector has.

Q Is Pakistan on the brink of collapse?

A Everyone is always waiting for the Centre to collapse and declare a breakdown. Everyone is waiting for the Taliban to capture Islamabad to believe that Pakistan has fallen. Pakistan has fallen. You don't have to wait for the headline.

Q Really, you believe that?

A Even under Musharraf, there were always three mutually hostile poles of power in the country: Islamists, civilians and the military. That is a political civil war. You could then argue that Pakistan is in an eternal civil war. Yes, it is eternal—until the state changes shape. I don't think Pakistan will continue in its present geographical form. Every couple of years, the map of the world looks different. The relationship between borders, people and resources is always in flux. We should not be sentimentally wedded to any country as it appears today.

Q Speaking of being wedded to a country, how do you define yourself?

A I'm a New Yorker. Every other identity requires qualification. I could say I'm Indian but an American citizen. Again, I have to qualify my Indianness because India won't give me my passport back because they haven't changed the dual citizenship law. The Indian government is too afraid to give it to people like me because there are about 20 million of us.