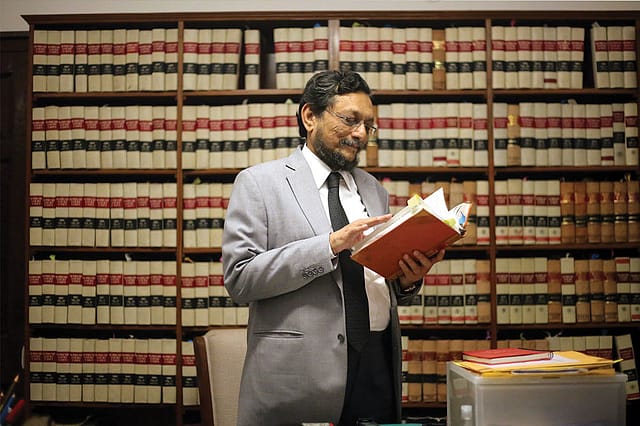

Sharad Arvind Bobde: A Man for All Reasons

FOUR SUPREME COURT judges went public about their concerns on the institution's functioning in January 2018. Six months later, the apex court had upheld that the Chief Justice of India (CJI) was 'Master of Roster'. By the time Justice Sharad Arvind Bobde took charge as India's 47th CJI on November 18th, the position had become mightier than ever.

For the judge who rode a borrowed Harley-Davidson, an episode which came to light because he had an accident fracturing his ankle that kept him away from the bench for a few days earlier this year, the professional mantra is justice, much like the Norwegian proverb 'It is the law that judges, not the judge.' Between his passion for motorbikes and a non-controversial career, he is seen as a liberal and conventional judge—someone of whom expectations are running high.

"He takes his work seriously. My impression is that he would like to bring about some changes in the Supreme Court through the use of technology, which may not necessarily be reforms, but a tweaking of the existing system," says former Supreme Court judge Madan B Lokur, one of the four judges who had revolted in 2018. The two share an interest in cricket and table tennis. They had played together in a bar versus bench match, and have been planning a table tennis match with each other, which is yet to happen.

Lokur recalls the judges' traditional weekly lunch day at the court when Bobde was marshal, a role entrusted with the power to penalise a judge who breaks the lunch rules and announce the end of the feast. The two would have a "friendly tussle" when Lokur would try to depose him. "He would take it in good spirit… But, he wrongly believed that his beard was better than mine," he quips.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Bobde, 63, took oath at the Durbar Hall of Rashtrapati Bhavan on a bright sunny morning, incidentally coinciding with the beginning of the Winter Session of Parliament, in a black judicial robe, a white, stiff wing-collared shirt and a neatly trimmed, short-boxed grey beard. In his tenure as a Supreme Court judge since April 2013, he has seen more than just black-and-white.

Past months had posed difficult times for the CJI. On January 12th, 2018, four Supreme Court judges— J Chelameswar, Ranjan Gogoi, Kurian Joseph and Lokur— at a press conference, went public with their differences with the then CJI Dipak Misra, underlining that the CJI was just the 'first among equals'. Three months later, in another unprecedented move, 64 Members of Parliament from seven opposition parties submitted a petition to Vice President Venkaiah Naidu seeking Misra's removal. The apex court was hearing a petition filed by senior advocate Shanti Bhushan alleging that the manner of allocation of cases by the CJI reflected 'a pattern of favouritism, nepotism and forum shopping'. In May this year, another shadow fell over the CJI, this time concerning Misra's successor, Ranjan Gogoi. A Supreme Court employee accused him of sexual harassment and Bobde headed a three-judge panel that gave a clean chit to Gogoi in April this year. Last month, Bobde headed a two-judge bench, which directed the Committee of Administrators presided by former Comptroller and Auditor General of India Vinod Rai to demit the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) office, paving the way for running the board's affairs by elected members. Bobde has been on the apex court bench in historic judgments, including the recent Ram Janmabhoomi-Babri Masjid title dispute, which ordered for the land to be handed over to a trust to build a temple and the Sunni Waqf Board to be allotted an alternate five-acre land for a mosque; the right to privacy in which the court ruled that it is an intrinsic part of the right to life and personal liberty under Article 21; and the Aadhaar case, ratifying an earlier order of the Supreme Court and clarifying that no citizen without an Aadhaar card can be denied basic and government services in 2015. The right to privacy ruling was seen as having paved the way for decriminalisation of homosexuality in India.

"Bobde is cut and dried. He goes by the letter of the law," says Vikas Singh, former president of the Supreme Court Bar Association. He recalls his first appearance before Bobde in Mumbai when it took him less than two minutes to grant Singh an interim order on whether the right to information (RTI) will apply to deemed universities. When he is not busy with judicial matters, Bobde often indulges in photography.

SEVERAL LAWYERS, WHO have known Bobde, describe him as a sharp and quick decision-maker. The Nagpur-born Maharashtrian, who comes from a family of lawyers, was enrolled as an advocate of the Bar Council of Maharashtra in 1978. Additional Solicitor General in Supreme Court Atmaram Nadkarni, who has known him for about two decades, says that as a young lawyer, he recollects that Bobde could rise above his prejudices and grant relief if one made out a case. "A well-read man, who had read the scriptures of almost all religions, Bobde was very clear about the fundamental principles of law." Nadkarni remembers how during the Goa State Cooperative Bank case, when matters related to finer principles of administrative law were decided, a lot of English laws were cited and Bobde was aware of every judgment of the House of Lords. He was elevated to the Bombay High Court in 2000, as Additional Judge, and sworn in as Chief Justice of Madhya Pradesh High Court in 2012. Hopes are high as the new Master of Roster, a role giving the CJI the privilege to constitute benches to hear cases, takes charge.

"The CJI's office is more compromised in the name of Master of Roster in constitution of benches and distribution of matters. In Justice Bobde, our hopes are that he will reverse this trend and politically sensitive matters will not be sent to certain benches," says senior Supreme Court advocate Dushyant Dave. He describes Bobde as a judge dictated by justice, with robust common sense, independent views and free of ideological influences, and hopes that he will appoint a committee from within for structural reforms.

An advocate for Bhushan, who had argued that the authority of the CJI as the Master of Roster to allocate cases to benches should not be reduced to an "absolute, singular and arbitrary power", Dave had referred to the Judges case of 1998 to argue that the Supreme Court itself had interpreted the term 'Chief Justice of India' to collectively mean the CJI and his four senior-most judges. In his petition, Bhushan had said 'absolute discretion' cannot be confined in just one man, the CJI. The bench, comprising justices AK Sikri and Ashok Bhushan, however, declared it was the exclusive authority of the CJI to allocate cases to fellow judges. Sikri's judgment did underscore that the CJI was the first among equals. The Supreme Court had reinforced for the third time in eight months that the CJI was the 'Master of Roster'. One of the verdicts called the CJI an 'institution in himself'.

These developments should, however, be seen in an evolutionary context. From 1981, when the apex court delivered a judgment in what is known as the 'first judges transfer' case to 2015 when the court struck down the Constitution (120th Amendment) Act—that provided for the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC)—the higher judiciary virtually carved out an independent role for itself. The original Constitution had a role for the executive in the appointment of judges. But with developments from 1981 to 2015 that was brought down to almost nothing. This period roughly corresponded with the weakening of executive authority in India. This was largely a function of governments being dependent on unwieldy coalitions in which the balance between the different organs of the state changed dramatically from what prevailed after Independence. With the return of a strong executive, it was natural that this would change. The NJAC, which provided for government representation in the decision-making system for appointment of judges, was one solution. In the years after the NJAC was struck down, there has been re-thinking within the judiciary about re-balancing. This is not just about an institutional balance but also about realising that courts are not a solution to all the complex problems that confront India. This has, however, been vicariously interpreted as an erosion of the judiciary's imprimatur. The debate has died down since then.

According to Lokur, who along with the three other judges had tried to drive home the point that the CJI was only the 'first among equals', the role of Master of Roster has suddenly gained importance in the recent past. "I don't recall any controversy over it in the courts I worked in earlier. It's for the CJI to decide what assignment is given to whom. But, when something inexplicable happens, you begin to wonder. This is what led to questions about the exercise of powers of the Master of Roster. Bobde should factor in conventions which have been followed in the past and accept that all judges are equal." He recalls how when he was heading a regular bench, the then CJI HL Dattu requested him to sit with him as a junior judge and he had agreed. "It was courtesy on his part to ask me and treat me as his equal. The 'first among equals' is a very important principle to follow."

The four judges had acknowledged that the Master of Roster was a convention important for orderly transaction of business, but said this was not recognition of superior authority of the Chief Justice over his colleagues. They had implied that Misra was allocating high-profile cases to favoured colleagues, without naming anyone but mentioning 'junior judges'. At that time, Justice Arun Mishra was tenth in the hierarchy and was sitting on certain benches hearing crucial cases. The four judges, all of whom have retired, may believe their press conference served its purpose in a way, leaving an unmistakable mark in the country's judicial history, but far from the clout of the CJI diminishing, it seems to have emerged as the second-most powerful position in the country. Gogoi retired as CJI recently after a rush of landmark judgments, just like his predecessor. As senior Supreme Court advocate Sanjay Hegde puts it, that in their brief tenure, each of them tries to leave their stamp on the institution. "Some changes were brought about after the press conference. The CJI became more circumspect," says Lokur.

In the US, the Supreme Court hears matters en banc— all nine judges sit together, unless if a judge recuses from a matter, leaving no scope for the Chief Justice to decide on the roster of benches. In the UK Supreme Court, which has 12 judges, they sit in panels of five or en banc when it comes to crucial matters. In India, the sheer number and diversity of cases require more benches, carving out a more crucial role for the Master of Roster. As per data given by the Government in Lok Sabha in July 2019, there are 13,260 cases (of which around 4,000 are over 10 years old) pending in the Supreme Court, which now has 34 judges, the highest ever. Justice Ajit Prakash Shah, in the BG Varghese lecture in March 2018, said in the High Court of Australia that the Chief Justice "proposes" a roster for each sitting: "The power of assignment exercised by the Chief Justice is not determinative in any way, but merely recommendatory. In contrast, having, or claiming to have, unbridled power as Master of Roster can be a dangerous thing."

Jurists and constitutional experts maintain that the CJI's office in India was always powerful, further augmented by recent developments. "The events of the past few years may have ended up making the CJI more powerful. By being Master of Roster, he can use it to guide matters in a certain way. It's a curious mixture of innate tendency to conform to authority and administrative controls on working of the Constitution that renders the CJI as more than first among equals," says Hegde. According to him, every government is more comfortable dealing with a single source and so it's up to the CJI to determine the extent of government control.

Recently, the Supreme Court ruled that the office of the CJI will come under the purview of the RTI Act. While welcoming it, jurists are apprehensive about the exceptions. "The judgment has many exceptions on which any CJI's office could drag its feet. Let's see how it works on the ground," says Hegde. The court has said that confidentiality and the right to privacy have to be maintained and that RTI cannot be used as a tool of surveillance.

Vikas Singh says governmental control over judiciary is very strong. At the same time, he elucidates the power of the CJI. "The type of cases the Supreme Court is handling can make or break governments. That kind of power is that of a super government. Government is answerable after a five-year term, but the judges are not. They get into the terrain of the executive. They decide benches." The only thing that has changed is that the roster of work allocation is declared, bringing in some transparency.

Shah, in his lecture, had said there was little that outsiders can do to persuade this arm of state to open up. "Ultimately, the desire to be transparent and follow principles of rule of law and natural justice must emerge from within the institution itself." He said that the question that arises in the present context is whether this power of being Master of Roster is unfettered and can be exercised without due attention being paid to convention or transparency and fairness.

But this was before the Supreme Court in July 2018, reinforced that the CJI would be the Master of Roster, a role that Gogoi, one of the four rebelling judges, was next in line for.

The task before Justice Bobde has got more challenging— an opportunity that can be missed or gained— over the next 18 months. The ball is now in his court.