Still Sitting Ducks

How long do we go on congratulating ourselves for our resilience? Can we ever hit back at terror? Our intelligence and response systems are still in disarray, our shores remain extremely porous. India needs to get its act together very quickly

Rahul Pandita

Rahul Pandita

Rahul Pandita

Rahul Pandita

|

18 Nov, 2009

|

18 Nov, 2009

/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/cover-duck-1.jpg)

Our intelligence and response systems are still in disarray, our shores remain extremely porous. India needs to get its act together very quickly.

At least we are clear about one thing now: before last year’s Mumbai terror attacks, India was incapable of ensuring the safety of its estimated 1.14 billion people, an exercise which takes not just a defence apparatus but also what the Government calls ‘intelligence’. That is why a foreign citizen called David Coleman Headley could enter India nine times between 2006 and 2009, visiting seven cities. Till July 2008, he ran a visa agency in Mumbai. But, as details begin to emerge after his arrest in the US last month, Headley was no ordinary tourist or businessman; as America’s Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) has documented, he was a terror operative, working at the behest of the Pakistan-based terror group, Lashkar-e-Toiba, in preparation for deadly attacks on Indian targets. Headley’s visa agency, it turns out, was a front for a cell recruiting young men for terror operations.

On being asked why New Delhi failed to detect his presence in Mumbai for a recce before 26/11, Union Home Secretary GK Pillai replied, “Primarily, they (Headley and his associate Tahawwur Hussain Rana) had come before 26 November 2008, that is why.” But what Pillai did not mention was that four months after the Mumbai attacks, Headley was in Delhi, this time for four days, apparently for selecting new targets for terror strikes like the Army’s National Defence College. And had it not been for the FBI’s intervention, his evil designs could have been executed. “The problem,” says former National Security Advisor Brajesh Mishra, “is that specific intelligence is not always available, but even on incomplete information, some preventive measures could have been taken.” The Centre took none. It was caught unawares, as always.

CENTRAL INTELLIGENCE AS OXYMORON

So, post 26/11, are we capable of handling such attacks in a different way should they, God forbid, happen again? “Why do you bring God into it?” asks veteran police officer KPS Gill, “You can be sure they will happen again.” This is a bleak thought for 25-year-old Bharat Shyam Navadiya, an aam aadmi who cannot be sure whether he will reach home safely in the evening. At least for Navadiya, it really doesn’t matter very much anymore. In the Mumbai attacks, he lost his wife right in front of him after she fell to bullets fired by terrorists at the Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus (CST). “The politicians are responsible for this sorry state of affairs,” he says bitterly. “How can the common man feel safe? Such instances will happen again and the Government will be caught napping,” he lets off some steam.

But does any of the huffing and puffing by Indian citizens leave the slightest sign on the bullet-proof screens of India’s political leadership? Is there enough condensed vapour there to finger-write just one single word, ‘HELP’? Security experts have for long been raising alarms over the befuddlement with which India’s leadership grasps public security issues. “There can be no policy coherence in a situation where policymakers lack even a rudimentary understanding of strategy and security,” says KPS Gill. That, on the ground, essentially means that the Indian State cannot even conceive of pre-emption. After all, such measures require a great deal of gumption, and more importantly the strategic wherewithal to act swiftly at the opportune moment.

And, who is supposed to show that swiftness? To begin with, the country’s intelligence institutions. Does India’s Intelligence Bureau (IB) have what it takes to counter terrorist threats? Well, decide for yourself. The total strength of the Bureau—from peon to director, as a security expert puts it—is about 28,000 personnel. Less than half of them do anything resembling intelligence work. And even among these, only 3,500 are actually engaged in the task of field intelligence gathering—on all issues, not just terrorism. The expertise crunch is not all. Ajit Kumar Doval, a former IB chief, likens the Bureau to a power generation unit. “The gap between the installed capacity and actual production must be met,” he asserts. The task for the new IB chief, Rajeev Mathur, then, seems daunting indeed. Without a radical rehaul of the IB to meet a new set of challenges, it will continue to be what it has been all these years, known for the menace it can pose to those who fall afoul of the party in power, rather than a terror deterrent.

As for the police intelligence of India’s assorted states, they are only capable of gathering crime-oriented inputs; in any case, most of the staff is either on VIP duty or busy spying on political rivals. That makes it nearly impossible to detect a terror attack before it unfolds. To put this in perspective, if the country’s intelligence gathering was up to the mark, India might have caught Headley long before the FBI did. Doval is among those who think the FBI’s revelations point to how Indian agencies botched up the case. “I think following the 26/11 investigations, we should have reached Headley much earlier than the FBI—they developed a very innocuous lead of his making a mention during a chat that the people responsible for the Danish cartoons need to be punished. This led them to find that he was claiming to be providing immigration services in Copenhagen, whereas no such company was registered,” he says, contrasting the FBI’s approach with that of Indian agencies, “In India, Headley had many devious linkages and had travelled on suspicious missions nine times. During the investigation of the case, if it was pursued with precision and dexterity, some leads should have surfaced pointing at him.”

“The intelligence agencies have almost no access to modern surveillance gadgets and other technological aids,” says Maloy Krishna Dhar, former IB joint director. After the Mumbai terror attacks, the Centre created the National Technical Research Organisation (NTRO) along the lines of America’s National Security Agency (NSA) to provide technical intelligence. Mumbai’s 26/11 attackers had made extensive use of sophisticated gadgets and telecom devices with switchable Sim cards to speak to their handlers across the border. But unlike America, whose agencies have access to spy satellites and aircraft, the NTRO, which works directly under the Prime Minister’s Office, has not been able to deliver much so far. “It is a still-born baby,” says Dhar. As a result, what the snoops end up doing is check records of hotels and cyber cafés which terror suspects may have visited.

The US has been far more proactive. In January 2009, the US Congress passed the Camera Phone Predator Alert Act, which makes it mandatory that mobile phones make a sound when a photograph is taken, on concerns over spying. “In India, we know how much terrorist sleeper cells use internet telephony applications like Skype, and yet we allow their usage,” says Dhar. Doval cites Headley’s example as a point in case. “Even before 2006, he had been visiting India, probably as Daood Geelani. When he changed his name to David Headley, our electronic data analysis should have alerted us to that,” he says.

As for the creation of yet another investigation agency, National Investigation Agency (NIA), experts believe these are purely symbolic exercises. Concerns have also been raised in the past about lack of coordination between various agencies, which, experts believe, can be easily traced to ego issues. “There is definitely a deficiency in the coordination between central and state intelligence agencies that needs to be corrected,” says Brajesh Mishra.

WHO DO WE BLAME, THEN?

At the top of the intelligence gathering pyramid is the National Security Advisor, Mayankote Kelath Narayanan, a former IB chief. After 26/11, Narayanan was pulled up by Prime Minister Manmohan Singh for the clear lapses in India’s intelligence mechanism. But amidst a rising din for his stepping down, nothing really happened. So, while intelligence agencies grope in the dark, terrorist groups like the Lashkar have been able to establish sleeper cells all over the country. Worse, as Headley’s case has demonstrated, there is not much India has been able to do about it.

Many senior operatives of the Indian Mujahideen, the group held responsible for serial blasts across India, are still at large. “As long as these cells continue to exist on our soil, the possibility of engineering future 26/11s will persist,” says Ajai Sahni, executive director of the New-Delhi based Institute for Conflict Management. The far greater problem, of course, is that even after Headley’s exposure, we won’t be able to draw any lessons from it. According to records available with the Foreigners Regional Registration Office, about 140,000 foreigners stayed back in the country between 2005 and 2007 after their visas expired. This includes 40,000 Bangladeshis, 289 Afghans and a similar number of Pakistanis. Most of them are believed to have been able to procure Indian identification papers such as ration or voter cards.

The typical policeman in khaki, the beat constable at the bottom of the pyramid, is caught up in a morass making ends meet with no incentive to do his job. And yet, as KPS Gill says, it was the extraordinary courage displayed by lathi-wielding constables that gave us what is now known to the police about 26/11 by capturing Ajmal Kasab alive.

Ajai Sahni puts it like this: “Putting up ‘NSG hubs’ and creating special forces such as ‘Force 1’ in Mumbai cannot substitute for improvements in general policing capabilities.” Adds Mishra, “If someone knew about the terror attacks and didn’t tell somebody in the police, then you have failed.” According to the former national security advisor, the policeman on the street must be made the nucleus of the fight against terror. “I emphasise that in fighting terror and more so in preventing it, the role of the police force is very important. Our police force has not been trained to deal with terror, only law and order,” he says.

Political interference in the recruitment and posting of police officials has resulted in a demoralised force, a point that Home Minister P Chidambaram raised at a conference of state police chiefs in the capital two months ago. “The average policeman on the street must earn the respect of the people,” says Mishra, “If people do not have confidence in him, they will never come forward to share the information they have.” In the war against terror, information is a precious commodity. But the problem, some say, is the prevailing inability to give credit where it is due, which suffocates sources of worthwhile strategic inputs from people who are at the bleeding edge of counter-terrorism responses, or have jigsaw pieces that could fit genuine intelligence (as opposed to a cut-paste frame). “We do not appear to have the capacities to build institutions, and rather, are far more adept at undermining and destroying the institutions that exist,” says Gill.

TROUBLE DOUBLED

That is one end of the faultline. Apart from dealing with terrorism aided and abetted externally, India is fighting losing battles on many other fronts. The Naxal problem, for instance, is one of the biggest challenges India has ever confronted. In the recent past, New Delhi has shown some seriousness in dealing with it, but that is not translating into much on the ground. Besides, much of the Northeast continues to be at the mercy of dozens of insurgent groups. In Manipur, for instance, extortion is rampant in the absence of the State’s authority. Talks with Naga insurgent groups have not made much headway either. During its ceasefire with the Centre, Nagaland’s main insurgent group NSCN(I-M) has continued arms procurement and recruitment operations, apart from extortion rackets (its budget is an estimated Rs 200 crore). The group is also believed to have links with the Islamist terrorist group, Harkat-ul-Jihad-al-Islami.

The real horror is that India may be getting a little too used to terror. Whenever there is an attack, all people do is ascertain the safety of family and friends. Then they go back to their TV sets. Only to watch leaders mumble: “This won’t happen again.” That’s a sign that it will happen again. And again. The fact is: India can’t ensure the safety of its 1.14 billion people.

Additional reporting by Haima Deshpande

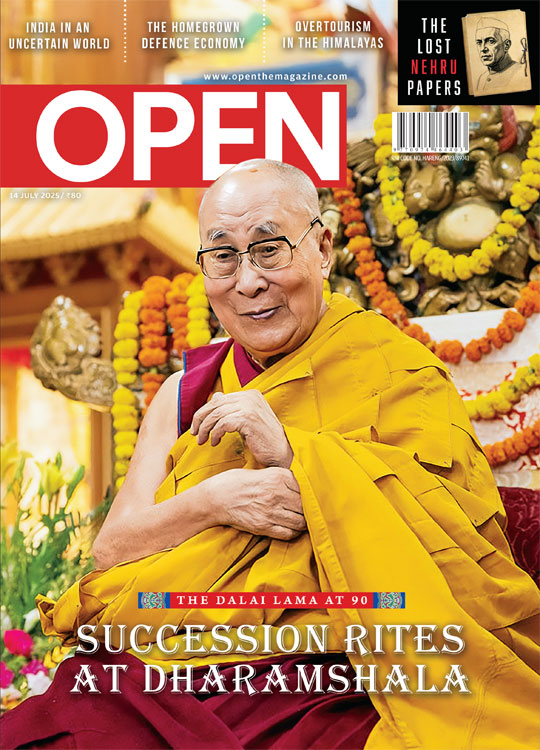

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover_Dalai-Lama.jpg)

More Columns

The brilliant bowlers of Birmingham Aditya Iyer

Beijing Wants a Monk In Marionette Strings Kush Sharma

Alongside Dharavi Recast, Adani Lines Up Goregaon, Malad, BKC Slum Clusters Fast-Fast! Short Post