In the Forecourt of History

When Modi skips the Throne Room on Inauguration day, it will be a sign of the people's Prime Minister

When Narendra Modi drives in to take his oath of office as Prime Minister of India, he would be the country's third prime minister to have his swearing-in conducted in the forecourt of Rashtrapati Bhavan. The first was Chandra Shekhar. Months of anti-reservation agitations against the recommendations of the Mandal Commission led to the internal collapse of the Janata Dal in the winter of 1990, leading to VP Singh's exit and the emergence of the shortlived prime ministership of his rival, Chandra Shekhar, supported by a Rajiv Gandhi-led Congress. Chandra Shekhar was keen that the ceremony be shifted from the spiffy and ostentatious Ashok Hall to the forecourt of Rashtrapati Bhavan.

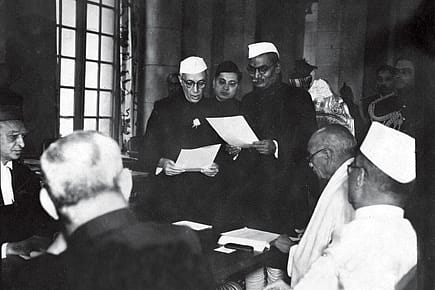

Chandra Shekhar was eager to show that he was 'one of the ordinary Indians' and wanted the participation of as many people as possible in his swearing-in ceremony. The Durbar Hall was originally the Throne Room of the Viceroy's House conceptualised by Edwin Lutyens, the architect of the stately building. In this high-domed hall—the ceiling covered with paintings of hunting expeditions — the Viceroys held State functions. On the night of 15 August 1947, this was the very venue for the swearing-in of Independent India's first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. Every Prime Minister since then, following a tradition set by the British, preferred to be sworn-in inside the renamed Durbar Hall, which has a limited seating of 500 people. After Chandra Shekhar, it was in 1999 that Atal Behari Vajpayee, as the head of the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) Government, opted for the forecourt over the Hall.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

The Grand Vision: In the late 1920s, when Lutyens sat finalising the building plan of the Viceroy's House atop Raisina Hill, he planned the forecourt as an annexure to the structure. Apart from adding to the grandeur of the building, the forecourt enhances its ceremonial nature. The vast open court with its grand steps leading to the state entrance of Rashtrapati Bhavan overwhelms any visitor. It is in this forecourt that every ceremonial procession has been meticulously planned and implemented with precision over the last eight decades. The red sand (bajri) that is spread over the grounds of the forecourt adds dramatic colour and augments the majestic aura of the Bhavan. But the dust raised by presidential horses during ceremonies forced a relook at the available options. Finally, archival material provided a solution to those who did not want to change what had been prevalent for decades. Red bajri had been used ever since the building came up, it was argued, and the issue was settled. The only new instruction was that the sand should be made finer and water sprinkled regularly to keep the dust down.

Ceremonies and Rituals: Independent India inherited all the rituals attached to official ceremonies and processions. Since the time of Nehru, little has changed in the ceremonies attached with the swearing-in of a president or prime minister, except for the thrones once used by the Viceroy and Vicerine, which were sent off to a storehouse. It was the Prime Minister who took the lead in formalising many of the ceremonies of high offices. Nehru was keen to do away with ostentatious rituals that were part of a colonial system where the monarch and his representatives were treated as superior to those they governed. But he did not want to discard all the ceremonies only because they were started by India's colonial masters. It is for this reason that little has changed in the ceremonies attached with the swearing-in of a president or prime minister, except for the thrones of course, which are currently displayed in the Rashtrapati Bhavan museum. The niceties of protocol remain much the same. A look at the protocol arrangements for the swearing-in of Lord Louis Mountbatten as India's first Governor-General will establish as much. Even the Presidential Body Guard traces its history to Governor-General Warren Hastings, who raised the mounted cavalry in 1773.

Official Garb: A look at archival material reveals that the achkan and churidar, commonly seen as traditional wear in India, entailed serious discussions and deliberations among India's top leaders. Again, Nehru took the lead in starting a conversation on what should be the formal dress for top office-bearers of the country. In a letter to President Rajendra Prasad, three days before the Constitution of India was adopted in 1950, he mentioned various options that could be considered. He did not seem to like the idea of a kind of 'university gown' suggested by C Rajagopalachari as the official attire for the Governor- General, President and Prime Minister. He finally suggested a black achkan and white churidar as the official dress, pending discussions later. It, however, gained acceptance over a period of time and was made an official dress for the President. Prime Ministers, however, in recent decades have preferred a bandhgala with trousers as their official dress when travelling abroad.

Security: Finally, Modi assumes the prime ministerial post with perhaps the highest levels of security ever. The buzz is that around 500 Special Protection Group personnel will be deployed for the Prime Minister's security henceforth.

It would be interesting to recall a note from Jawaharlal Nehru, dictated to his principal personal secretary on 9 July 1949. The Nehru Papers reveal that he was always uncomfortable with security men milling around him. After the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi, Nehru was asked to move out of his bungalow at York Place to Teen Murti House—the former residence of British India's Commander-in-Chief. The note, which can be found in the Selected Works of Jawaharlal Nehru, reads: '…to line up policemen or troops from Palam to my house or where I travel… During these visits I have found far too many policemen in cars and trucks accompanying me, as if I was leading a reconnaisance force against some enemy.'

(Sunil Raman is the founder of the website, Monumentaldelhiwalks.com)