His Master’s Mind

He is as feared and admired a politician as his mentor. His strategic skills and organisational acumen are as legendary as the controversies that swirl around him are never-ending. PR Ramesh embarks on a journey in search of the real Amit Shah, variously described as the man who holds the key to Narendra Modi’s conscience, a ruthless artist of realpolitik , the smartest spin doctor in town and the man nobody dares mess with. A definitive portrait

/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/amit-shah.jpg)

A journey in search of the real Amit Shah

The hotel in Muzaffarnagar where Amit Anilchandra Shah is staying tonight has several oversized chairs in the reception, an indication of the kind of visitors he is expecting. Jostling for a darshan with the man who has been given the unenviable job of winning Uttar Pradesh for Narendra Modi are legislators, candidates, friends and a gaggle of journalists. Just back from a whirlwind tour in the hinterlands of western UP, the portly grandmaster of the electoral chessboard shows no sign of exhaustion. He praises some, chides a few, and in between speaks in chaste Gujarati on his cellphone to—who else?—Narendra Modi. After all, in the political lore of India 2014, Modi and Shah form a rare brotherhood built on trust. If there is one man who holds the key to the mysteries of Modi’s mind, that man is said to be Shah, who, for many within the party and outside it, remains as inscrutable as his master.

Shah, 49, gets less than five hours sleep these days. The BJP general secretary has to catch up with those he couldn’t meet the previous night, even after a long wait lounging in those huge chairs. Shah has more phone calls to make as he tucks into his favourite carrot parantha, mildly sweet and delicious with curd. He prefers a heavy breakfast, which would include buttered toast, several kinds of fruit, idli and vada. He starts off with milk mixed with hot water.

“I am blunt. If I convey a message, I will not nuance it to the extent that the very intent is lost,” says Shah, who is almost always accompanied by controversy. The latest one is over charges of a ‘hate speech’ he made in Shamli for which an FIR has been filed against him. This comes after the so-called ‘snoopgate’ scandal in which he faced allegations that he had ordered surveillance on a woman architect.

He looks unaffected by such diversions— he has survived bigger ones, including a Congress plot to get the CBI to arrest him in the Ishrat Jahan encounter case. He is undeterred by calls from opposition parties for a ban on his campaigning in the state.

Several BJP leaders Open spoke to say the BJP is back in the reckoning in UP thanks to Shah’s mind and methods. “He is very passionate and leaves nothing to chance. He is someone who doesn’t take ‘no’ for an answer. He has always been a doer and therefore we are not surprised by what he did in UP,” says Shankarbhai Chaudhary, BJP’s Gujarat general secretary and MLA from Radhanpura. The BJP won only 10 seats last time in the country’s most populous state, which accounts for more Lok Sabha seats than any other, but the party is upbeat about its poll prospects this time around, forecasting 40-50 of the state’s 80 seats. Shah is the one who backed the idea of pitching Modi from the temple-city of Varanasi as part of a strategy to make major gains across the state, especially in the eastern belt of Poorvanchal, where the party has been weak. “Amitbhai’s mind works like a machine gun,” says a BJP functionary in UP.

BJP leaders contend that it is Modi who deserves the credit for tapping his abilities—something the party’s prime ministerial candidate has done for long, says Gujarat’s law minister Pradeep Singh Jadeja.“I met Modi when I was 17 years old. It is a 33-year-long association,” Shah says proudly. As Modi’s minister, he has handled 12 crucial portfolios, including home, parliamentary affairs, home guards, excise, law and justice, and transport.

In 1982, when they met, Shah was an RSS activist and Modi a pracharak in charge of youth activities in Ahmedabad’s Mahanagar area. Modi was so close to Shah that when the late RSS Sarsanghchalak Balasaheb Deoras asked him to join the BJP, the young Shah was one of the few people with whom Modi shared his apprehensions about the proposed role. “[Modi] was initially reluctant,” remembers Shah, “‘How can a square peg fit into a round hole?’ was his worry.”

By 1995, when the BJP was already in power in Gujarat, their association had grown thick. Modi had a mission and Shah was the implementor. The Congress was still a powerful force in the state with formidable influence in rural areas, cooperatives and sports bodies. “The BJP decided to systematically make deep inroads into the Congress bastions,” says Shah, now relaxing in his hotel suite. Both knew it was a long haul.

The first task was to challenge the Congress hold over rural Gujarat. They worked on a simple calculation—that for every elected village pradhan, there was an equally powerful and resourceful leader who failed to make the grade. The defeated headman was not ready to play second fiddle, nor ready to wait five years. Shah and a few of his handpicked assistants approached defeated pradhans and “set them up” as “a rival pull of attraction”. In no time, there was a network of 8,000 pradhan challengers working for the BJP, Shah recounts.

The next task was to demolish the Congress hold over sports bodies, especially in cricket and chess. Shah was in charge of an operation that resembled aggressive raids in the corporate world, and, after sustained effort, the BJP managed to dislodge the Congress from all sports bodies. This denied the rival party an important source of patronage.

The takeover would not be complete so long as Gujarat’s powerful cooperatives, whose role in the state’s economy was paramount, remained in Congress hands. The same strategy was employed here as well, notes Shah.

Of the 28 elections—to the state Assembly and various local bodies—that Shah has fought since 1989, he says, he has not lost a single one. It was in 1998 that he fought his first election to a primary cooperative body. The next year, he became President of Ahmedabad District Cooperative Bank, the biggest cooperative bank in the country. Elections to such bodies are usually won on caste considerations. Such banks have traditionally been controlled by Patels, Gaderias and Kshatriyas, and he managed to win despite the cooperative sector being a no-go zone for Banias.

When he took charge, the bank was on the verge of collapse. With a share capital of Rs 38 crore, it had accumulated losses of Rs 36 crore. He turned it around within a year, and the bank registered profits of Rs 27 crore. Its bottomline is in the Rs 250 crore region now.

Shah, now Modi’s most trusted lieutenant, was given charge of the state’s crucial home portfolio. Typically, chief ministers like to keep a vice-like grip on the home ministry, unless they are under pressure to appease a particular section in the party or an ally. According to senior colleagues who have seen the bond between the two evolve, it was Modi who encouraged Shah to diversify his interests. “Don’t give up reading Gandhi. Please read Vivekananda as well to broaden your perspective,” Modi used to tell him, says a party colleague, adding that Shah was also under the spell of his mother, who was deeply influenced by Mahatma Gandhi. When he was jailed shortly in 2010—on charges of ordering fake encounters as Gujarat’s home minister—after his mother’s demise, Shah spent his time in prison reading Lokmanya Tilak’s Gita Rahasya and Dayanand Saraswati’s Satyarth Prakash, which forms the core of Arya Samaj philosophy.

Senior BJP leaders say that it was BJP President Rajnath Singh, and not Modi, who put Shah in charge of party affairs in UP. Singh was impressed by the organisational skills that Shah displayed in wresting control of various Congress-run enterprises in Gujarat. And he wanted him to do more, elsewhere. Shah was surprised at Singh’s suggestion that he oversee the party’s affairs in UP. The BJP leader had expected to be put in charge of a small state like Himachal Pradesh.

A MAN WITH MANY FRIENDS

Uttar Pradesh had been crucial for the BJP’s successful power runs in 1996, 1998 and 1999, but a letdown in subsequent general elections. It was clear that the party could do well at the Centre only if it found a way to maximise its returns from the state. It was a challenge. For more than a decade, UP had been the graveyard of reputations of stalwarts like the late Pramod Mahajan who were unable to revive the party’s fortunes here. The state party unit was regarded as a virtual minefield, fraught with outsized egos and factional feuds, and with perceptions of the state’s status as a past pivot for saffron ascendancy adding complexity to the dynamics. The state was apportioned among squabbling ‘mahamantris’, which made the task of revival harder still for the party’s UP prabhari (in-charge); BJP sources say even Modi was worried about the odds stacked against Shah and the potential cost of failure.

For Shah, reluctance had given way to single-mindedness that has earned him the reputation of a ‘delivery boy’, a big departure for someone who says he is not interested in ministerial authority. “I am an organisational man. If there is one thing I aspired to, it was to become a general secretary of the BJP,” he says.

Over the past nine months, Shah has reached out to “all the egos and ambitions” that make up the state BJP, according to a senior party leader. Shah’s initial measures included sifting the party’s ‘have-beens’ from those with promise, opening the door to outsiders, and spotting potential among those languishing in the margins without mentorship. His natural approach was a blend of defiance and assertiveness on one hand and concessions to tactical needs on the other. Two months ago, Shah drew up a list of candidates who could hold their own against tough rivals in the Samajwadi Party and Bahujan Samaj Party, besides a few in the Congress. Diffidence had given way to a “jor ka dhakka iss baar (big push this time)” aggression.

Those who are worried about Modi’s ‘takeover’ of the BJP grudgingly concede that the approach was breathtakingly bold, and, at the same time, cunningly pragmatic. During candidate selection, past reputations were no insurance against a ruthless application of the winnability criterion, something that went against Murli Manohar Joshi, for example, in Varanasi. It was combined with the tact of appeasing bruised self-esteem. Every single hurt soul was tended to, with blandishments offered in the form of promises of later adjustments. The aura of potential victory invested these with a ring of credibility. In all, it was not a scorched-earth policy but a worldly approach of the kind that has helped Gujarati Banias flourish on distant shores, says a BJP leader referring to the likes of Shah.

Uttar Pradesh has often flattered to deceive so far as BJP is concerned and Shah seems to be aware of the pitfalls. This prompts him to register a note of caution when his seniors seem convinced that appearances will not prove deceptive this time. According to BJP leaders, Shah has consistently pegged the BJP’s estimated tally in UP at 38 to 40, a realistic number even by the reckoning of his opponents. (He got a call from his son Jay while Open was with him, talking about an opinion poll conducted by a TV channel. “You are also going by what they say. Don’t get carried away,” Shah senior told Jay.)

Shah is an out-and-out family man who cannot do without the company of his wife, son and close relatives. Yet, he keeps his kith and kin away from politics, a trait mostly seen among RSS cadres. Gujarat law minister Jadeja vouches for this, adding that the man was very close to his mother. Even if he came back late after party work, he would spend almost an hour with his mother, who didn’t sleep until the son came home. “He used to rest his head on her lap and talk to her about the family and enquire about her health,” says Jadeja, adding that it was tragic that Shah was arrested and jailed merely 13 days after his mother’s death.

Shah, who says he was born in Mumbai—rubbishing claims that he was born in Chicago—belongs to a wealthy family from Mehsana, where he finished his schooling before moving to Ahmedabad to study biochemistry. It was here that he was deeply influenced by the RSS and joined the organisation as a volunteer. The BJP heavyweight is reluctant to talk about the members of his business family. Shah briefly followed in father’s footsteps, starting a PVC pipe business. His grandfather, according to Jadeja, was a highly influential figure in Mehsana. Ask Shah about his family, and he replies, “Just leave it.”

Now, with perceptions gaining ground that the BJP could be within sniffing distance of power, a recent report in the media claimed that Shah could be a minister of state in the PMO. When asked about it, Shah is dismissive. “We are not so stupid to start counting chickens before they are hatched. For us, each seat remains a contest,” he says. “In any case, if I aspire to any job, it is to a role in the organisation. I am even thinking of taking a six-month break after the election.” But this is not going to stop speculation over the role he would play in a new dispensation if the BJP achieves power. Party circles are already agog with the way Shah has familiarised himself with the functioning of the ‘mayanagari’ (town of illusions) that is Delhi.

THE ROAD TO DELHI

Shah shifted to Delhi from Ahmedabad only because of a Supreme Court order that barred him from visiting Gujarat, even without—as his friends and sympathisers such as Jadeja and Chaudhary allege—giving him a chance to be heard. Shah was released on bail on 29 October 2010, a Friday. The next day, Justice Aftab Alam took up a petition at his residence to have him barred from Gujarat (since it was a Saturday, the courts were closed).

That evening, Shah visited Arun Jaitley at the latter’s residence in East of Kailash. Jaitley fetched the keys to a house he owns in the Bengali Market area and asked him to move there. “Dolly (Jaitley’s wife) has made all arrangements for your stay there,” Jaitley told Shah, who politely refused. “You are the Leader of the Opposition and my staying at your residence will give ammunition to the party’s rivals,” he replied. He and his wife moved to a room in Gujarat Bhawan instead. Now, when he is in Delhi, he stays in a flat in Jangpura.

But that reluctant visitor to Delhi four years ago has now familarised himself with the ways of Lutyens’ Delhi. “He knows about the orientation and preferences of ministers, bureaucrats, journalists, police officers and even judges. I think we have found our next organising secretary of the BJP,” says a BJP senior leader. Several others in the party also agree that Shah is cut out for such a role. “We have not seen such combination of pragmatism and ideological commitment in any other leader in recent years,” says another BJP leader.

That pragmatism was on display when Open accompanied him on an impromptu interaction with traders in Muzzafarnagar. In the presence of nearly 200 of them, Shah wasted no time in coming to the point he wanted to make. This Lok Sabha seat appears to be in the BJP’s kitty already. The region has seen communal violence in recent times and the perception that the state’s SP government has been biased towards Muslims has left even Jats and Gujjars—who have not been traditional BJP voters—looking up to the BJP for a change.

What could have been a neat political play, however, has been complicated by the Congress’ surprise decision to field a leader of the Bania community, traditionally friendly to the BJP.

When he got up to speak, Shah brushed aside assertions from the audience that he should not bother trying to win the seat and instead concentrate his energy on other areas. “No seat is won until it is won. Why do you think the Congress has fielded a Bania? Do you really expect the Congress candidate, who may be a good soul, to win? He has been inserted only to ensure the defeat of the BJP candidate. You all should forget the rest of UP and ensure that your votes don’t get split.”

Then came the emotive pitch about traders being harassed all the time by goons despite being tax payees who deserve respect. Within minutes, some people in the audience ushered in the cousin of the Congress candidate who professed his allegiance to the BJP. He was brought before a beaming Shah.

MASTER OF MEGA RALLIES

BJP honchos feel that mega rallies by Modi have an ‘aura of invincibility’. They often point to the size of these crowds to counter sceptics who deny a wave in Modi’s favour. Of course, the use of rallies as a ‘force projection’ tool is not a new phenomenon. But Shah’s approach has introduced a new element. The BJP may have spent huge amounts of money to hire 3D holograms and ferry large media contingents to these rallies, but Shah was not ready to waste money on arranging paid crowds. He worked out a plan.

For every village unit that falls in the zone of the venue of a rally, party workers were asked to hire one Bolero van each to transport people. This has been par for the course for all political parties. But what was different was that Shah refused to provide money for the hiring of these vehicles. Instead, what was offered was the prestige of being involved with the cause of the day. That it saved party funds apart, the big objective was to ensure that the worker who organised the Bolero became a leader of the village unit and that the nine or ten people who travelled with him to these rallies became converts. “He, therefore, developed a stake in the Modi project,” says a BJP local leader from Muzaffarnagar.

Shah is also a smart crisis manager. While Open was with Shah, he received a call from the tantrum-throwing sanyasin Uma Bharti complaining of ‘sabotage’ from within. “Didi, I hope you have a passport. Why don’t you travel to US to propagate Hindu dharma? By the time you return, you can take oath as an MP,” he told her, despite her protests. “Don’t you trust your brother? There is nothing to worry and you are winning by a huge margin,” said Shah, who was sent by the Sangh in 1983 to the ABVP, a crucible for youth leaders who have now emerged as some of the country’s best-known politicians.

Shah became an activist of the Bharatiya Jana Yuva Morcha in 1987. From ward secretary to taluka secretary, state secretary, vice-president, and then general secretary of the BJYM, he worked his way up. In 1995, when the BJP formed its government in Gujarat, he became the chairman of Gujarat State Financial Corporation. Shah has been an MLA since 1996, the year he was elected in a by-election. He went on to win Assembly polls several times again—1998, 2002, 2007 and in 2012. On each occasion, he improved his margin of victory.

Over the years, the RSS too started to see Shah as a big bet for the BJP. Among other things, what impressed the Sangh’s senior functionaries was his effort to pass a contentious piece of legislation in the Gujarat Assembly that would turn religious conversion—an issue that agitates the RSS and its offshoots—illegal.

The draft Gujarat Freedom of Religion Act was sent to Chief Minister Modi for his approval and cabinet’s consideration in 2003. When the draft reached Modi’s table, he summoned Shah. “Won’t this face resistance inside and outside the Assembly?” he asked Shah. State BJP leaders note that it was Shah who convinced Modi that the bill would pass without much trouble.

And it did. Modi was not present the day it was tabled and okayed in the House, but its enactment was aimed at making it difficult for religious groups in Gujarat to actively proselytise and convert people from one faith to another.

The Act, which is being challenged by opponents, outlaws the use of ‘force’ or ‘fraud’ to secure anyone’s conversion to another religion. Also, it requires people seeking to convert somebody to ask for the permission of the local District Magistrate, who must also be informed by any such convert of his orher conversion in writing. ‘An offer or any temptation in the form of any gift, gratification or grant of any material benefit, either monetary or otherwise,’ the Act decreed, would be illegal. While opponents argue that this goes against the rights guaranteed by the Indian Constitution and could be misused, Shah states that it is only a measure against ‘forced conversions’.

He adds that he is not someone who rests on his laurels. After all, being an election strategist is nothing new for him. Over the years, he has handled several Lok Sabha campaigns for LK Advani in Gandhinagar.

In Gujarat, Shah is seen as a shrewd tactician. He is also very emotional, says Chaudhary.

“I keep looking ahead,” Shah says. After juggling phone conversations and meetings, he sets off on another day’s gruelling tour of the interiors of UP. This is perhaps the first time since the legendary organisational man Sunder Singh Bhandari’s tenure as the party’s point man in the state that a leader has managed to strike such a strong chord with ordinary party workers.

Shah pauses before walking away to his Innova. “In 2005 itself, I knew that Modi had in him the qualities to lead the country. Only a person who can do hard work can succeed,” he says.

As the politician who has worked so hard to conquer Delhi is closer to his destination, there is a man behind him working even harder for his master’s success. There is no reward higher than this for Amit Shah.

About The Author

CURRENT ISSUE

MOst Popular

3

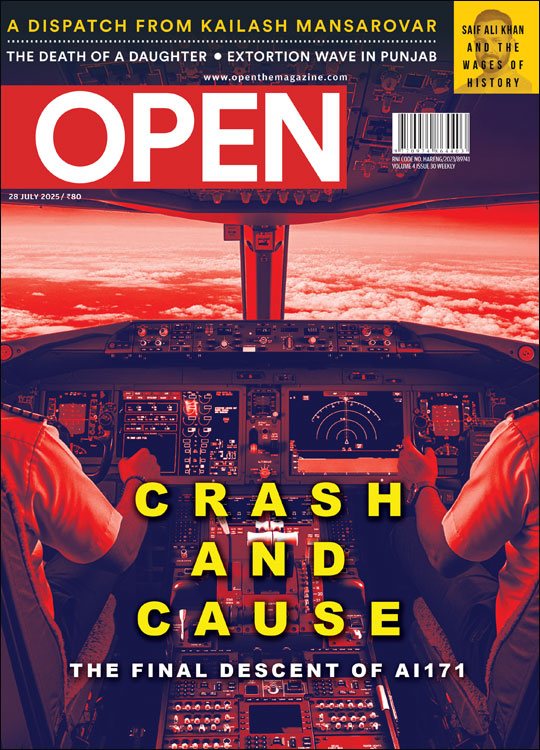

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover_Crashcause.jpg)

More Columns

Bihar: On the Road to Progress Open Avenues

The Bihar Model: Balancing Governance, Growth and Inclusion Open Avenues

Caution: Contents May Be Delicious V Shoba