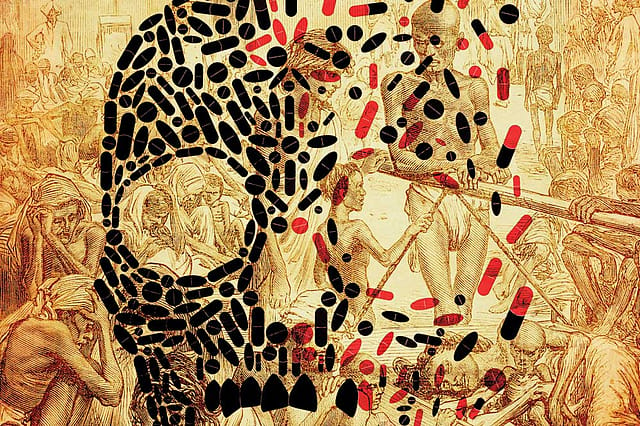

The Virus That Killed 18 Million Indians

ON THE 10TH of November, 1918, |Mahadev Desai, the personal secretary of Mahatma Gandhi, began his diary entry with, 'Influenza raging in the Ashram'. He then went on to quote verbatim a letter that Gandhi, in a disease- stricken weakened state, wrote to one Gangabehn—'I could read only today your card telling me that you, Kiki and others had fallen ill. I was glad to learn, however, that by the grace of God you are all progressing. The body of the person who has chosen to follow the dharma of service must become as strong as steel as a result of his holy work. Our ancestors could build such tough bodies in the past. But today we are reduced to a state of miserable weakness and are easily infected by noxious germs moving about in the air. There is one and only one really effective way by which we can save ourselves from them even in our present broken state of health. That way is the way of self-restraint or of imposing a limit on our acts. The doctors say, and they are right, that in influenza our body is safest from any risk to life if we attend to two things. Even after we feel that we have recovered, we must continue to take complete rest in bed and have only an easily digestible liquid food. So early as on the third day after the fever has subsided many persons resume their work and their usual diet. The result is a relapse and quite often a fatal relapse. I request you all, therefore, to keep to your beds for some days still. And I wish you kept me informed about the health of you all. I am myself confined to bed still. It appears I shall have to keep to it for many days more, but it can be said that I am getting better. The doctors have forbidden me even to dictate letters, but how could I have the heart to desist from writing to you?… Vande Mataram, Mohandas Gandhi.'

The disease that Gandhi alludes to and almost forgotten in India's cultural memory was the Spanish Flu, one of the biggest killers that mankind had ever seen in recorded history. Around the world, it is estimated to have claimed between 50 to 100 million lives. And in India, which was the worst affected, within the space of just a couple of months, it could have killed as many as 18 million or 7 per cent of the total population. The flu came in three waves. The first, which arrived in summer, wasn't very markedly different from a seasonal variant. But exactly a 100 years ago, in September 1918, after a ship of soldiers returning from World War I landed in Mumbai, the second lethal wave began. From Mumbai it radiated to the rest of the country and the bodies kept piling on.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

In her book Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed The World published last year, Paris-based science journalist Laura Spinney did an indepth biography of the pandemic. In 2013, she had been in the Italian Alps, writing about archaeologists who were pulling out of the melting glaciers remains of World War I and the experience made Spinney wonder why no one talks about the Spanish Flu which had occurred at the same time. "In the back of my mind I had a sort of suspicion that the Spanish Flu killed many more people but I didn't know that for sure. Thanks to Google I was able to establish that within a few seconds. I thought it was really interesting that we don't look back at it too much, why is it not in our memory?" she says, over the phone.

Flu pandemics occur at regular intervals because new mutated strains of the virus jumps from birds and animals into humans. Spinney says that in the last 500 years there have been around 15 pandemics. In the 1890s, the Russian Flu killed a million. And after 1918, there were three pandemics and the worst killed about 2 million. The Spanish Flu, on the other hand, claimed at least 50 million and that makes it a huge anomaly. The explanation is that it arrived in a world at war. Usually when a new strain emerges, it starts off as very virulent and then tempers itself to survive as a species. It needs to keep the host alive long enough so that the person can move about and infect others. However, in 1918, because of World War I, millions of young men were packed together into trenches on the western front for long periods of time. "In that particular situation it wasn't in the virus' interest to moderate its virulence. There was no evolutionary pressure to do that. So it just raced through the trenches, killing as it went. And then when you get those troops finally going home, if they survived, they take the virus with them," says Spinney. The war ended on November 11th, making it worse because soldiers returned to different corners of the world. "It is hard to think of a better vehicle for spreading a lethal respiratory disease," says Spinney.

A2014 PAPER, 'The evolution of pandemic influenza: evidence from India, 1918–19', published in the journal BMC Infectious Diseases noted that the 'the wave originated in and radiated from Bombay on the west coast, and is suspected to have arrived in India on a troop ship carrying soldiers home from the First World War in Europe. Different regions of India experienced successive episodes of peak mortality… In terms of severity, Bombay, the Central Provinces, and parts of Madras were hardest hit.'

The paper's author, Siddharth Chandra, director of Asian Studies Centre at the Michigan State University, had been working on an unrelated project on colonial India, for which he needed annual population statistics. He used data from the census of India, which was taken once every 10 years. When he looked at the figures for the Censuses of 1911 and 1921, he noticed that the population had grown far more slowly than it should have given the trajectory from prior decades. 'It did not take long to discover that this was due to the devastating effect of the 1918 influenza pandemic. I became interested in the influenza because, in those days, India was the largest country in the world [it included what is now India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Burma (Myanmar)]. So the influenza pandemic as it played out in colonial India was an event of great demographic and epidemiological significance not just locally but also globally,' says Chandra over email.

There is debate over the exact number of deaths Spanish Flu caused. Chandra's estimate of population loss for the directly ruled provinces of India is 14 million but he adds that the number would be larger if we included the princely states. 'The majority of the deaths occurred in October and November 1918,' he says. Mumbai was the starting point in India because it was a major entry point for Indian troops returning from Europe after fighting in the war. 'From the pattern of spread, I suspect that the virus may have entered India independently from Madras [now Chennai] as well. It was a major garrison town at the time, and one of the earlier places to suffer the effects of the pandemic,' he says. 'The influenza appears to have spread throughout India through transportation networks, most notably the railway network. The general pattern of spread was from the west and south to the north and east.'

As the flu radiated outwards, its virulence began to diminish while the duration of the wave increased. Chandra says that it is not certain why this happened but there are a few theories for it. 'One theory is behavioural—it is possible that authorities [and the population more generally] in areas that were affected later had heard about the approaching epidemic and were able to take precautions to reduce its effects by reducing contact with others [infected people] and being more conscious about hygiene. Another theory is a biological one—we know that viruses evolve as they spread, and a virus that is highly virulent and short-acting has a lower likelihood of perpetuating itself. So it is possible that the virus was evolving into a more benign one as it travelled [i.e. more benign variants were becoming the dominant ones as the disease spread]. A third theory relates to the weather [and climate], which vary significantly across the different parts of India. It is possible that the conditions in the eastern part of India were less favourable for the spread and virulence of the virus than those in the western part of India,' he says.

Climate seems to have played a key part for India being so badly affected. The arrival of the flu coincided with a drought that the country was reeling under then. "It led to famine in large parts of the country, so the flu is going to pick on people who are already weak. Public health provision was massively underpowered. On top of that a lot of doctors were away at the war. Death rates were higher in cities than in country areas as a rule. Bombay was a very unhealthy place at the time because you have refugees flooding in from the countryside who were starving. Population of the city was swollen and there was also cholera, because of the refugee problem," says Spinney.

Another peculiarity of the Spanish Flu in India was it was the only country where more women than men died across all age groups. "One theory is that women tended to eat less well. Boys and men were given priority where food was concerned in many households. Women were also more likely to nurse the sick. Not only were they more exposed to the disease as a rule but they were also less resistant because they were more likely to be malnourished. There may have been a factor of vegetarianism, it is not clear," says Spinney.

The after-effects of the pandemic were long lasting. For example, it became a catalyst to the idea of governments providing universal healthcare. In India, it is even theorised at having given an impetus to the freedom movement. The British found themselves incapable of managing the pandemic and called for the communities to assist. Spinney says, "This is where you see a lot of local and caste organisations mobilising, coordinating themselves and stepping in in a magnificent manner. In political terms, what was interesting was that it got grassroots organisations talking to each other and going out into remote areas and coming into contact with people like Adivasis and different parts of the communities. It created a lot of bridges. Certain historians argue that it mobilised the grassroots and connected it up to the national movement. National organisations were providing the resources, the money, medicines, blankets and so on with which the local organisations went out to help the population. So you see this kind of coalescence of the whole movement."

If it killed so many and had such deep impacts, why is the pandemic unremembered? Spinney postulates a few reasons, the primary one being that World War I made for a better memory even though it claimed less lives at around 18 million deaths. The second reason is that when the pandemic was happening, people didn't know what they were dealing with or what to call it. "How do you find it in the historical records where it goes by many different names? There wasn't a kind of overview of it," she says. Scientific understanding was sketchy. For example, that flu is the result of a virus was not known. They also didn't know at the time how many it had killed. In 1927, the first estimate believed that 22 million died. This was revised to 30 million in the late 1990s. "Then again to 50 million to 2002. Most of the 20th century, people believed that it hadn't killed many more people than World War I. There wasn't a sense of this vast wave of death which we do have now. It is a pandemic in which the memory appropriate to the scale of it has taken a good century to form," she says.

WHAT WOULD HAPPEN if a similar lethal flu came into being today? Medicine has developed. There were no anti-virals in 1918. We now know the exact cause and development stages of a pandemic; and organisations like World Health Organization (WHO) can coordinate global responses. Vaccines can be developed within months. There is no World War to accentuate the pandemic. But according to Lalit Kant, former head of the Indian Council of Medical Research's Division of Epidemiology and Communicable Diseases, India needs to be even more worried. "Population density has increased. Proximity between animals and human beings has increased. Urbanisation and unplanned growth has happened. People are living in crowded conditions. It is a disease communicated by cough and sneeze, so more people together means more infections happening. We have no [flu] vaccines being used [in India]. We have malnutrition. We have an older population which is increasing. We have this combination of factors even if the infection were to come now," he says.

Recently, Kant co-authored an article in the Indian Journal of Medical Research titled 'Pandemic Flu, 1918: After hundred years, India is as vulnerable' and it referred to a modelling exercise that had shown 'if an influenza pandemic with a similar severity were to happen in 2004, the world is likely to have around 62 million deaths. And sadly, India again would top the countries with maximum deaths [approximately 14.8 million]'.

Kant says that how India deals with a flu pandemic is entirely dependent on the infrastructure we create to deal with seasonal flus. His paper gives the example of what happened when Swine Flu, declared as a global pandemic by WHO, emerged in April 2009. Developed countries that were used to both taking and manufacturing flu vaccines responded with speed while the rest floundered. The paper said, 'By August 2010, when the pandemic was declared to be over, 214 countries had reported confirmed cases and 18,449 deaths. The first pandemic vaccine to be approved was in September 2009…The manufacturers of seasonal flu vaccine [of which more than 80 per cent doses are produced by seven large manufacturers located in the US, Canada, Australia, Western Europe, Russia, China and Japan] switched over to making pandemic vaccines. There were reports that the developed countries had placed large advance orders for the 2009 H1N1 vaccine and bought all that the vaccine manufacturers could produce, leaving very little or nothing for the rest of the world. As a result, no pandemic Influenza A/H1N1 vaccine was available in majority of the low resource countries before January 2010—more than eight months after the WHO declared the pandemic.'

In India the first case of Swine Flu was reported in May 2009 and while the government imported vaccines and also funded Indian vaccine manufactures to produce it, people were found reluctant to take it. Much of the vaccines were not used and had to be destroyed. 'By end of 2010, India had recorded 38,730 cases and 2,024 deaths. Due to limited testing facilities, this is likely to be an underestimation of the true number of cases in India,' mentions Kant's paper.

Kant says that we have a couple of vaccine manufacturers in the country but because we don't have a culture of flu vaccination, their capacity to produce large number of doses is still small. "To increase capacity, we must use influenza vaccine in India. And only then if the pandemic happens in India, these very vaccine manufacturing companies would be able to make available an influenza pandemic vaccine," he says. Also, people will accept a pandemic vaccine if they have taken a regular flu vaccine earlier.

What we also miss is that dangerous flu outbreaks happen anyway with alarming regularity. It is localised and so doesn't get national resonance. Just this January, an outbreak of Swine Flu had infected hundreds of people in Rajasthan. 'Many people died [in Rajasthan]. Last year [there was an outbreak] in Gujarat, the year before that in Maharashtra. So there have been outbreaks happening in India that have gone unnoticed. It is not that we cannot do anything. It is political will that is needed,' says Kant. And should one of these strains mutate like that in 1918, it might just be too late to do anything.