Risks and Returns

India has little to lose in embracing France tighter, working closely with AUKUS and prioritising nuclear submarines

Sudeep Paul

Sudeep Paul

Sudeep Paul

Sudeep Paul

|

24 Sep, 2021

|

24 Sep, 2021

/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Risks1.jpg)

(Illustration: Saurabh Singh)

PRIME MINISTER Narendra Modi is in the US at a time when the world is in the midst of a geopolitical shake-up and diplomatic friendly fire centred on submarines. His host, US President Joe Biden, has by now proved, for better or for worse, that old men are not boring and that ‘normal’ is not synonymous with anodyne. How much of Biden’s attention to the Indo-Pacific is genuine and sustainable concern about containing China, especially the misadventures of the PLA Navy, and how much an attempt at deflecting the blowback from the Afghanistan disaster need not occupy us now. The Biden administration has sent out its most unambiguous geopolitical message since assuming office in green-lighting the AUKUS (Australia-UK-US) alliance whereby the US and the UK will help Australia build a fleet of nuclear-powered submarines.

Nuclear submarines, as all things nuclear, were a taboo for Canberra for long. As recently as 2016, when the deal with France’s Naval Group was struck, Australia was thinking only in terms of conventional submarines that would help it cut a little back on the enormous advantage that the PLA Navy enjoyed. Thus, the Holy Grail Canberra sought was a diesel-electric boat that could match a nuclear sub in performance. At the same time, thinking on the subject was undergoing an evolution down under. The PLA Navy might be able to match the US Navy to a stalemate in the Taiwan Strait today should China decide to invade the island. Extending that possibility to the larger South and East China Seas in the near future, the Australians, along with the Japanese, had a serious problem at hand. And time was running out.

It was increasingly being felt that the only option for the Royal Australian Navy was nuclear-powered submarines. Since the deal with the French had run into trouble, and since Washington was now offering licence-manufacture of the SSN-X class of next-generation nuclear subs, why not cut out the unnecessary friend in the national interest? Writing in The New Statesman, Australian strategic analyst Rory Medcalf argued: “This new triple near-alliance is based on capability, convergent interest and, above all, trust. It will be easy enough to caricature as an outmoded Anglosphere” but could end up being “nothing less than a merger of military, industrial and scientific capabilities”.

One only hopes Biden is as ruthless with China as he has been with France. The AUKUS does not exist as a formal alliance yet and while a submarine project can take a decade to bear fruit, the Indo-Pacific, recognised as the hottest global theatre for the present and the near future, will not be left to the PLA Navy. But Biden’s diplomatic ham-handedness might cause a rethink in Paris. France, an old hand in the Indo-Pacific, could pour cold water along with Germany on the recalibration of the European Union’s (EU) strategic position vis-à-vis Beijing which it had so far been enthusiastically leading. The loss of a near-global consensus on China even as the maritime ante is upped around the PLA Navy would be a tactical success set against a strategic failure.

The Indian Navy’s lacuna of nuclear attack subs needs to be addressed before the PLA navy patrols too close for comfort. France could be India’s saviour notwithstanding the costs

For Modi and India, prima facie, there is a twofold opportunity in the developments. The scheduling of the September 24th in-person Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) Summit was against the backdrop of two significant facts: first, Biden’s persistence with his predecessor’s focus on the Indo-Pacific and the alliance of the US, Japan, India and Australia to counter the PLA Navy’s rise; second, the possible addition of muscle to the Quad by the AUKUS alliance. The UK had returned to the region quite a while ago but irrespective of the ambitions of a post-Brexit ‘Global Britain’, no one is claiming as of now that the US will retrench in the face of China, at least not anytime soon. But the question also arises as to what exactly will happen to the status of the Quad now. Is it to undergo an elevation or fall by the wayside with the emphasis on a renascent Anglosphere in the Far East? The opportunity for New Delhi is there, but it may not be unadulterated joy.

On the other hand, France has been one of India’s most steadfast defence and security partners, to say nothing of standing by India even after the Pokharan tests of 1998. An aggrieved France, complaining of being stabbed in the back by allies and standing to lose upwards of $60 billion in the full fallout of the scrapped deal with Australia, will calm down but not easily unburden itself of the hurt. India will not merely do itself a favour by cosying up to France further. As the world’s second-largest arms importer (never a happy thought in itself) making up almost 10 per cent of global arms imports of late and looking to indigenise defence manufacture, it is time India leveraged its strategic partnership with France beyond one-off deals with their decades-long controversies.

India needs to prioritise its own nuclear submarine fleet of which, apart from INS Arihant, which is actually an SSBN-class nuclear-powered boat that fires ballistic missiles, it has nothing to show. The INS Arighat will not be ready for another year at least and the lacuna of nuclear attack subs needs to be addressed if the Indian Navy is to see itself through the coming years when the PLA Navy is certain to patrol in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) too close for our comfort. France could be India’s saviour notwithstanding the costs. But since the Russians don’t come cheap these days either, a substantial partnership with India could keep France engaged with the Indo-Pacific and clear-sighted on China. India’s own SSN project calls for speedy prioritisation and Paris could hold the key to it.

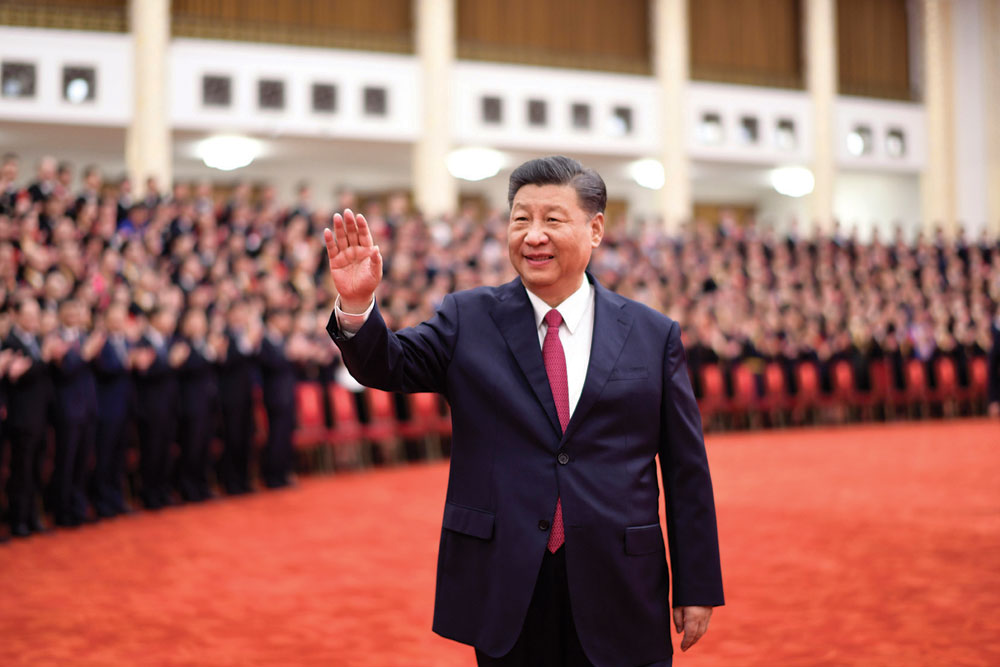

ON FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 17TH, Taiwan’s air force scrambled fighters after nine or 10 PLA Air Force aircraft entered Taiwan’s air defence zone. It was the 13th consecutive day China had violated Taiwan’s airspace. On September 16th, Taiwan had announced a $9 billion addition to its military budget to counter the Chinese threat. After the incident, three experts, all with intimate knowledge of Beijing, warned that an invasion of Taiwan is not far off. The most significant of these was perhaps the assessment of Admiral Philip Davidson, former commander of the US Indo-Pacific Command, who told Nikkei Asia, “I think the threat is manifest during this decade—in fact, in the next six years.” Summing up Davidson’s claim, the newsmagazine said: “Xi is widely expected to stay in power beyond the next quinquennial national congress of the Communist Party in the autumn of 2022. But when the party convenes again five years later, in 2027, there could be a transition…which may impact the decision to move on Taiwan.”

The PLA Navy might be able to match the US Navy to a stalemate in the Taiwan strait today. Extending that possibility to the South and East China seas in the near future, Australia and Japan, as well as India, have a serious problem at hand. And time is running out

Around the same time, Nigel Inkster, former deputy director of MI6, told LBC News that China has almost given up on non-military options for annexing Taiwan. Beijing is “edging closer” to war with the US over Taiwan and he would rate the chances of such a military confrontation “as high as eight, on a scale of one to ten”. Also speaking to LBC, David Rennie, the Beijing Bureau Chief for The Economist claimed that it was not a question of ‘if’ but ‘when’ China would invade Taiwan. “If you are the Chinese leader you cannot go down in history as the guy who allowed Taiwan to get away,” Rennie said, implying that Xi Jinping is not likely to leave the Taiwan question around for his successor to answer. The only consideration for the Chinese is the certainty of success. Beijing will not commit to an assault on Taiwan unless it is sure of victory but that does not mean it will hold back forever.

The Indo-Pacific is heating up fast and that’s the view from both Beijing and the capitals of the consort of democracies that want to counter the threat. The AUKUS signals the intent to concretise a Cold War-like old-school, tight alliance in the new cold war—a sort of innermost circle within a wider circle of allies. Since the military dimension is intrinsic to AUKUS, would Washington still feel enthusiastic about an essentially non-combative Quad beyond the odd summit in the coming years? The most optimistic reading for India is that it has nothing to lose in sticking to the Quad and also working closely with the US and Australia. However, in an irony that cannot be missed in South Block, AUKUS is handing India back its long-held obsession with “strategic autonomy”, in that it is free to do what it chooses with, above all, France as well as Russia.

India’s Project 75I, currently looking for six new conventional diesel attack subs, is budgeted at a little above $8 billion, almost half the fighter aircraft budget at $15 billion. The project is currently at the stage of contender evaluation. Since submarine projects take notoriously long and the reality that Canberra looked in the face vis-à-vis the PLA Navy pertains precisely to New Delhi too, by the time the first of these six submarines is operationally ready, buyer’s remorse could be an understatement. In all likelihood, China will retaliate in speeding up the PLA Navy’s SSN deployment in the IOR. Of its 74 subs, reportedly six are SSNs or nuclear-powered attack boats; China has four SSBNs or ballistic missile submarines; and 50 diesel-electric boats. India has a total of 16 operational submarines. Even 75I spent two-plus decades in gestation till it was cleared by the defence ministry in June this year. Its full scope of building 24 new submarines by 2030, with six SSNs, is a long way behind schedule. Project 76, which morphed into 75I, involves an extension of 75I with wholly indigenously designed subs.

If India is going to be a player and partner of consequence in the Indo-Pacific, let alone pose a credible deterrence to the PLA Navy, it needs to distribute its eggs among the right baskets. The US is unlikely to help India acquire technology for SSNs, something it has repeatedly claimed—before AUKUS—it was reluctant to transfer to even its closest allies. The fact is, nobody has been very forthcoming with India on naval nuclear technology, not even France. That is why it is imperative for New Delhi not to miss any of the winds of chance blowing from the Indo-Pacific, and certainly not the scent of French anger.

When a Submarine Brought the World Close to Catastrophe

AS FAR AS SUBMARINE disappearances go, 1968 was a year unlike another. Four submarines sank that year in circumstances yet to be conclusively explained. Three of these subs were diesel-electric but the fourth, USS Scorpion, was a nuclear sub. Along with the Soviet K-129 that sank on March 8th, the Scorpion, which went down on May 22nd, has scripted one of the most intriguing and scary chapters of the Cold War, less than six years after the Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962.

The centrality of submarines to the Cuban Missile Crisis, and the fact that the most dangerous element in the mix was underwater, was not revealed till as recently as 2002. The Soviets had dispatched four Project 641 (Foxtrot, as NATO called the class) submarines armed with nuclear torpedoes—to be deployed if deemed necessary. One of these diesel boats, B-59, was desperate to surface ‘to breathe’. Detected and depth-charged by US warships, Captain Valentin Savitsky was about to launch the nuclear torpedo but Vasily Arkhipov, the deputy brigade commander aboard the sub, reportedly convinced him to stand down.

Arkhipov, an unsung hero of humanity, may or may not have saved the world from nuclear war—as the launch of the torpedo would have presumably begun—but the genesis of the nuclear submarine lay in what W Craig Reed has graphically described in Red November: Inside the Secret U.S.-Soviet Submarine War (2010): “Carbon dioxide, the Achilles’ heel of diesel submarines and the odourless killer of sailors. The most any smoke boat could stay underwater running on batteries before the air became stale and sailors risked CO2 poisoning was three to four days. They were then forced to come shallow and run the diesel engines to push out the old air and pull in the new.” Savitsky’s Foxtrot had almost run out of air and since surfacing meant surrender, he had brought the world close to annihilation.

The SSN did not need to surface to recharge its batteries. A diesel boat could not match it for speed. But what the SSN needed was a high-calibre reactor which did not come without its problems. Nuclear subs were not met with enthusiasm from sailors even decades after the first boats were deployed. The mantra “Diesel boats forever!” was very dear to the old crews, unless they had a near-death experience in suffocation. In any case, while diesel-electric boats are still the mainstay of conventional subs, they never were competition for nuclear-powered submarines.

About The Author

MOst Popular

3

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover_Crashcause.jpg)

More Columns

Bihar: On the Road to Progress Open Avenues

The Bihar Model: Balancing Governance, Growth and Inclusion Open Avenues

Caution: Contents May Be Delicious V Shoba