Look Who’s Cancelling Hinduism

Targeted violence during festivals like Ram Navami has a long history going back to the Mughal era

/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Hinduism1.jpg)

The aftermath of violence on Ram Navami in Sasaram, Bihar, April 1, 2023 (Photo: AFP)

COMMUNAL TENSION that began around the Ram Navami celebrations at March-end continued to fester in many places, spilling over into mid- April. A clash broke out on April 8 in Jamshedpur in Jharkhand over an alleged desecration of a Hindu religious flag. Police enforced prohibitory orders but incidents of stone-pelting and arson continued, forcing security personnel to conduct flag marches in various parts of the state.

Earlier in March, several towns in Bihar were rocked by violence between groups that saw the use of explosives. In Sasaram, Bihar Sharif and Nalanda, communal tensions erupted over three long days. Hundreds were injured after miscreants stoned and fired at a Ram Navami procession in Bihar Sharif. It did not end there. Two days after a bomb blast injured six people in Sasaram town of Bihar’s Rohtas district, another explosion was reported in the Mochi Tola area of the town in the early morning hours, as part of violence and arson that marred Hindu celebrations across the state. It spread to Gujarat, Jharkhand, and even West Bengal, repeating a pattern from last year. But in sections of the media and among the commentariat, there were efforts to form a narrative that pointed to plotting, allegedly by “riot-mongering Hindus”.

Nothing could be farther from the truth than this victim syndrome projected so effectively the world over by Islamists, with long-suffering Israel being a prominent victim. Today, a cycle of violence between Hamas and the Jewish state persists and there is heightened concern with the Islamic holy month of Ramadan and Jewish Passover coinciding. This has led to deaths and authorities imposing restrictions in and around the Al-Aqsa mosque and rounding up potential troublemakers disguised as innocent pilgrims and devotees. Deaths were reported on both sides.

In the context of the subcontinent, the brutal violence unleashed by the invading Islamic armies on the Hindu citizenry morphed, over time, into a carefully crafted narrative of “meek and peaceful” minorities being hounded, especially during Hindu festivities like Ram Navami, by mobs of the majority community. That mainstream narrative peddled an account whereby Hindus wantonly took out processions through areas dominated by Muslims, loudly chanting ‘weaponised’ “Jai Shri Ram” slogans meant to intimidate residents of the area. The Vishva Hindu Parishad (VHP) was accused of turning this religious slogan into a war cry as part of its communal agenda in the late 1980s. Most versions told of how mobs deliberately stopped before a mosque, hiking up the decibel count of slogans through megaphones. Or, how a splash of colour on a mosque wall led to a clash on Holi. The standard version hard-sold the viewpoint that the violence that marked celebration of Hindu festivals was, one way or another, triggered by Hindus themselves to create communal tension and keep the minorities intimidated.

The real threads of unvarnished history, from as long ago as the 18th century, tells a very different story over a period of 350 years or more, which rips up these tutored narratives. Sample these: In Sylhet in 1782, violence erupted after Muslims demanded that Hindus stop their religious ceremonies during Muharram. This was repeated in 1786 in both Balpur and Berar. In Benares in 1809, tension and violence broke out over a mosque built by Aurangzeb at a place where a temple stood; in 1871, violence flared up between the two communities when Muharram and Ram Navami fell on the same day; and Hindu-Muslim riots were witnessed during Hindu festivals in Bareilly, Delhi and Etawah in 1887 and 1886, respectively. In 1729, a row over fireworks that fell on a Hindu jeweller’s palki near Jama Masjid sparked prolonged violence that ended with the jeweller’s house being razed and other Hindu properties being destroyed.

British administrative records on the 1871 Bareilly riots maintained: “A portion of Mahomedan community had resolved at all costs to attack and plunder the Hindu procession… The procession was a very large one… The priest (Mohunt) who performed the puja left the grove, and the procession returned homewards. The Mohunt was set upon by a band of Mahomedans on his way and murdered… The Mahomedan mob fell back upon the city, causing much rape and bloodshed.” In Salur, a Hindu festive procession was attacked by Muslims in 1891 and, in 1910, violence broke out once more in Ayodhya over the slaughter of cows by Muslims. The list is unending.

Since the time of Aurangzeb, there had been a ban across the Mughal Empire on religious processions, construction of temples, especially those of a particular height and scale, and a strict “no” on practically anything that would have infringed on the glory of Nizam-e-Mustafa (the Order of the Chosen One). Processions and music that marked Hindu festivities since time immemorial were seen as blasphemous for the iconoclast Muslim rulers who drew their inspiration from invaders and plunderers who styled themselves as “butshikan” (slayer of idols). Abu Nasr al-Utbi’s Tarikh-i-Yamini vividly records various attacks on temples, including the one most revered by Hindus, the Somnath shrine. “After the Sultan has purified Hind from idolatry, and raised mosques therein, he determined to invade the capital of Hind, to punish those who kept idols and would not acknowledge the unity of God.” But, of course, Marxist historians like Satish Chandra, Romila Thapar and their followers maintain that Mahmud of Ghazni was attracted to the Somnath shrine in 1025 CE only by its riches and was not driven by religious bigotry or fired by the Islamic zeal to annihilate everything that came in the way of the glory of his faith. On the watch of these historians, all the inconvenient moving and contrary parts of history were streamlined into the contrived reality of Jawaharlal Nehru’s “Idea of India”. Under this spurious historical insistence, the violence that marks every Ram Navami procession, or unrest over cow slaughter, was shown as something engineered by VHP and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) as part of a sinister design to divide communities and engineer a Hindu vote-bank. The truth comes out when a court notes that stones and explosives were kept in readiness for the passage of a Hindu procession, as happened in Delhi’s Jahangirpuri last year.

The phrase ‘sensitive routes’ achieved positive outcomes for the government and the minority community at once—it absolved the administration, in a secular country, of its primary responsibility to ensure that all communities had an equal right to celebrate their festivals

Historian Sita Ram Goel detailed this brutal assault on Hindu religious ecosystems by the Muslim invaders. In a recent article, Sandeep Balakrishna referred to Goel’s observations: “On the eve of Islamic invasions, the cradle of Hindu culture was honeycombed with temples and monasteries… Hindus were great temple builders because their pantheon was prolific in Gods and Goddesses and their society rich in schools and sects, each with its own way of worship. But by the time we came to the invasion, we found that almost all these Hindu places of worship had either disappeared or were left in different stages of ruination.” This explains why, while the temple shrines of Madurai Meenakshi Amman, Thillai Nataraja in Chidambaram, and Brihadishvara in Thanjavur flourished in southern India, most major temple shrines in the north were decimated by the conquering Islamic hordes, leaving only huge mausoleums in vast swathes of northern India.

It was only after 1857, when Muslim resistance to British rule was snuffed out following the failed efforts to declare Bahadur Shah Zafar the ruler of Hindustan, Hindus began asserting themselves not just in the political arena but also in the cultural space. Brutal suppression of their religion and culture had for centuries compelled many to practice their traditions and beliefs surreptitiously but, eventually, the essence of their worship, which is community worship, began to manifest itself in various parts of the country. Coming out of their cocoon for the first time in centuries, the majority community flowered. Alongside this confidence grew resistance to cow slaughter, a standard toolkit used to taunt the subjugated Hindus and impress upon them the superiority of the ruling class. It was also aimed at differentiating between the two faiths. What followed was a series of riots.

This was not something limited to what is pejoratively called the “Cow Belt”. Resistance erupted in various parts of India where Hindus felt the time had come to reclaim an important aspect of their faith—to celebrate their religion, to serenade their deities in all their divine glory. It was a turning point, something that may not have meant much to settlers but mattered a lot to generations of people and societies that grew up hearing and imbibing the beauty of their religion and its gods and goddesses through oral and folk culture as well as by reading its epics and religious texts. For Hindus across the subcontinent, the pre-eminent deity was Ram, referred to by a variety of names and avatars and invested with every virtue. Each name of Lord Ram told an epic story in itself, taught an epic moral value, and endorsed a way of life. Each deity conjured up an enthralling, polychromatic tale.

In contrast, most Abrahamic religions throw up a single image of a successful general or a strategic tactician endorsed by the tenets and the Commandments. Abrahamic faiths may have their regimented gatherings but Hindus, through centuries, have been the most congregational religion. Processions and festivities, night-long bhajans and kirtans and socio-religious celebrations of the multifarious components of their many-splendored faith have been integral to the Hindu religion.

This, a fulcrum of religious practice, was savagely suppressed and smothered for centuries by Muslim rulers. So, when the tyranny that had suffocated the practice of their way of life was debilitated, ordinary Hindus came out to celebrate their traditions, beliefs and culture in a big way.

THE BRITISH COLONISERS who followed the invaders were not fair rulers either. They, coming from the same stream of Abrahamic faiths, were more ready to tolerate Muslim intransigence. Even decades later, when the Queen’s Proclamation extended equal rights to all subjects in the Empire irrespective of religion, it was clear that under the veneer of equality, the colonial rulers, in fact, favoured Christianity and were more accommodative of Islam in their reign in the subcontinent.

Their acceptance of Muslim intransigence, though, had much to do with Muslim intolerance and Islamic exceptionalism; it also had to do with a sense of entitlement that grew and persisted strongly in the community, with the attendant nostalgia for Islamic rule. All of this served to put their faith on a higher pedestal even when relegating Hindus, despite their overwhelming numbers, to lesser subjects. Syed Ahmad Khan’s founding of the Aligarh Muslim University in 1875 is viewed by many historians as part of a larger attempt to give young, upper-caste Muslims an English education and to claim a speedy and strident stake in the auxiliary ruling class that was imperative for the British. This was an audacious bid to shore up the elite position held by the community for centuries in the subcontinent, by playing handmaiden to the British rulers and at the direct expense of Hindus who had lived under oppression for centuries of Muslim rule.

Muslim representatives in the Constituent Assembly, meanwhile, would insist on the right to proselytise and oppose the uniform civil code. Despite the dominant narrative of a community reeling under an overwhelming sense of insecurity, the assertiveness and sense of entitlement continued, finding expression in the insistence that Muslim personal law be kept outside the jurisdiction of the sovereign Constitution. The right to propagate Islam found strident, almost militaristic, expression on the streets in the form of continued resistance to Hindu processions taken out during festivals like Ram Navami, to the staging of Ram Lila, to the opposition of Hindus on the issue of cow slaughter, and so on. The religious faultlines both persisted and thrived.

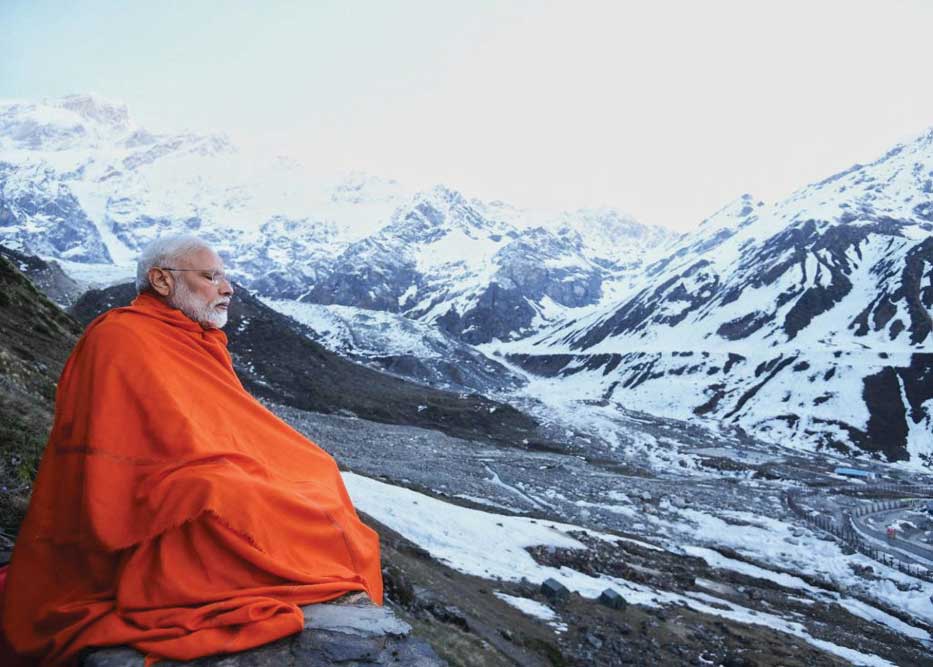

Narendra Modi has himself been the fulcrum of the transformation, proudly wearing the many shades of saffron as Prime Minister. He has made the celebration of being a Hindu the right of millions of Hindus who had laboured under insecurity and shame for so long

A premium was placed on this intolerance by the new rulers of independent India and the keepers of official records who were sponsored by post-Independence governments, despite the fact that it jarred fully with their loud proclamations of the so-called “Ganga–Jamuni Tehzeeb” and avowals of longstanding secular and multicultural traditions of the subcontinent. That same officially sponsored clique of historians, academicians and textbook writers justified, over decades, this hollow chorus of secularism with a variety of deceitful ploys, both intellectual and illogical. The letter writers protesting of late the right-sizing of certain parts of India’s Mughal history are the ones who wrote the distortions into school texts in the first place.

Consider two such ploys. First, the whole narrative on communal riots during Hindu festivities was read through a prism of “sensitive routes”—areas that the law and order authorities declared as most likely to witness violence. By and large, these were areas housing mosques, areas dominated by or with a substantial population of Muslims, and so on. In truth, this phrase achieved positive outcomes for the government and the minority community at once—it absolved the administration, in a secular country, of its primary responsibility to ensure that all communities had an equal right to celebrate their festivals. In essence, it meant that certain parts of the nation’s geography were unofficially declared ‘no-go zones’ for Hindus on days that mattered the most to them. Ironically, this endorsement of ‘sensitive routes’ to be flagged during Hindu festivals came loudest from self-declared ‘secularists’ who otherwise argue vocally against the ghettoisation of communities and open reference to parts of a city as “Pakistan”. Second, the administration was able to pat itself on the back by monitoring only select areas and communities. It appeared to matter little to the authorities that the best way to test their effectiveness in maintenance of law and order is to ensure the protection of rights and the safety of lives and limbs in challenging situations for all communities equally in all areas of town.

Moreover, the number of areas brought under the ‘sensitive routes’ category has been growing with every passing year and creeping into parts of the national map, even as the acceptance of Muslim intolerance is on the rise. At the same time, any public place, including roads, can be blocked for mass Namaz. Incidentally, those who cry themselves hoarse over alleged atrocities by rampaging Hindu mobs on innocent Muslim victims fail to raise their voice and insist, in the name of maintaining law and order, that processions by Muslims on Muharram and other such religious occasions should also be restricted to areas dominated by the community. A case in point is Karbala, in Delhi’s Jor Bagh. Karbala and Dargah Shah-e-Mardan are in the middle of Jor Bagh and BK Dutt Colony. The grounds are decked up for every occasion, including Nauchandi Jumerat, and Tazia processions starting from the Walled City end at Karbala in Jor Bagh. The eight acres of land owned by the Waqf Board also house the Rajdhani Nursery that the board claims has refused to vacate despite court orders and clashes erupted over this in 2012. Residents of Jor Bagh and BK Dutt Colony, meanwhile, maintain that Muslim religious events occur almost every fortnight, leading to immense inconvenience to residents, and that congregations have spread to public areas like parks, with no check from the authorities.

The violence unleashed by the invading Islamic armies on the Hindu citizenry morphed into a carefully crafted narrative of ‘meek and peaceful’ minorities being hounded, especially during Hindu festivities like Ram Navami, by mobs of the majority community

This is, in practice, a sectarian sequestration. The most distressing fact is the resounding silence of left-liberal intellectuals who choose to keep mum when Muslims carry out violent protests, shouting “Gustak-e- Rasool ki ek hi saza, sar tan se juda (Death is the only punishment for insulting the Prophet)”, but refer to Hindu religious chants of “Jai Sri Ram (Victory to Lord Ram)” as a war cry against minorities. This duplicitous game of open appeasement, one that has persisted for decades, is aimed at browbeating Hindu worshippers into restricting their religious celebrations to the four walls of their homes and making their devotion a private affair once again, while giving a blank cheque on this to minority communities. What makes the motive of administrations, apparently still suffering from a form of Stockholm syndrome, very clear especially with regard to the erstwhile ruling class of Muslims, is this: Abrahamic religions, by their very essence, are regimented and congregational. It is a bounden religious duty or farz for every Muslim to go to the mosque on Friday and for Christians to attend mass. Across the globe, it is a mass affair. Religion as a private affair was a Marxian prescription and, in India, was concocted only for Hindus and fitted into a planned tapestry aimed at forcing Hindus to subsidise ‘secularism’ at their personal and communal cost, and at the cost of their culture and belief.

HOWEVER, TWO DEFINING events have begun to change the story in India of late. The spread of the internet has revolutionised the dissemination of news hitherto monopolised by the “legacy media”. The internet has democratised news and widened its access manifold. It has ensured that sanitised and curated accounts of what led to communal unrests have become passé. There are now multiple accounts of the same event, multiple truths, if you will. Not just written reports but fresh audio and video reports posted instantly or fed live by citizen reporters have ensured that dominant versions of events are questioned and challenged. The suffering of majority-community victims, mostly played down in the news, is now directly visible to thousands, letting them form their own opinions rather than allowing motivated and politically manipulated news and opinions to rule.

The second development is one for which large sections of Indians can take credit: the elevation of Narendra Modi to the post of prime minister in 2014 and the re-election of his government in 2019. Although its response has been muted on many occasions— it is restrained by the Constitution as well as by the division of work that governs Centre-state relations—the very existence of the Modi government for nine long years has been extremely transformative for practising Hindus and for guarding equal religious and other rights for all citizens. Modi has himself been the fulcrum of this transformation, openly and proudly wearing the many shades of saffron as prime minister—something frowned upon since Nehru’s day—visiting key shrines, chanting shlokas and ensuring the repair and restoration of ancient and key places of Hindu worship. Modi has made the celebration of being a Hindu and taking proud ownership of the religion the very right and duty of millions of Hindus who had laboured under insecurity and shame for so long. Religious festivals, shrines and temples, and the Hindu way of life have begun taking centrestage once again. The construction of the Ram temple in Ayodhya and the initiation of a grand ceremony on a global scale on Ram Navami are proof that the guilt and uneasiness associated by the erstwhile ruling classes to the practice of Hinduism have now been exorcised. And this is just the beginning. For the first time in a very long time, “Jai Sri Ram” chants reverberate as loudly on Hanuman Jayanti as “Vande Mataram” and “Jai Hind” do on August 15 and January 26.

/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Cover-War-Shock-1.jpg)

More Columns

On Being Young Surya San

Why Are Children Still Dying of Rabies in India? V Shoba

India holds the upper hand as hostilities with Pakistan end Open