Exile and the Kingdom

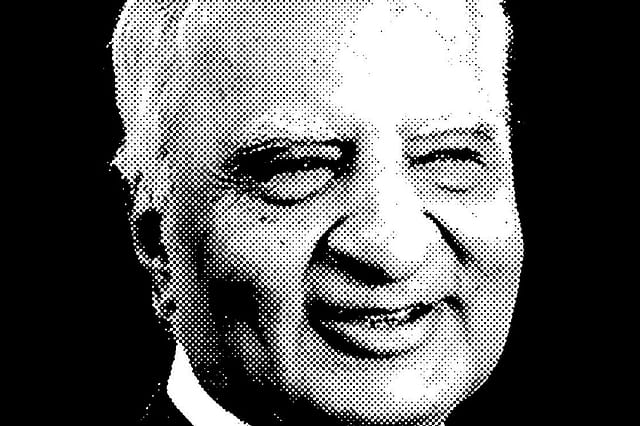

WE BEGIN TO SEE when we can no longer see. That's more of a truism than learning to hear after we lose our hearing. Yet, to be robbed of one of the senses is to experience all the others sharpened. Why else would history abound with blind seers? Ved Mehta, who died in New York on January 9th at 86, had been blind almost his whole life, having lost his eyesight in early childhood. Born to a fairly affluent family in Lahore, he could travel continents. And become an expatriate at an early age and subsequently an exile. Although 'exile' comes straight off the title of his autobiography series published over three decades, one is uncomfortable using the word as label for a man who felt at home everywhere and nowhere.

So what was Mehta in exile from? Perhaps the answer that comes nearest the mark is: himself. And perhaps for that very reason, he remained his most important subject, no matter what and where he wrote. That is not to commit sacrilege by taking anything away from Mehta's gamut of works about his country—or countries—and the world around him. In fact, the finest wonder of his writing is his descriptive acumen. More precisely, its ability to consistently describe what only an excellent pair of eyes could see and a sharp mind observe, preserve and process.

It was in many ways a matter of chance. Mehta became known as the writer who took India to the Americans because of his three-decade-plus career as a staff writer for The New Yorker, a position he could not have landed and held without William Shawn. Shawn is on record for pronouncing one of the best-known clichés about his protégé's skill: Mehta "writes about serious matters without solemnity, about scholarly matters without pedantry, about abstruse matters without obscurity."

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Mehta travelled, and he wrote. His most cited efforts would be his navigations through the history of India as it had happened and continued to happen. He wrote about walking Indian streets, Gandhi and whatever lay in his path and whoever caught his fancy. Thus he built a reputation as a profiler. His sharpness as an interviewer added to his growing weight at the New Yorker. But as usually happens when a disability lies, or is perceived to lie, at the heart of brilliance—or when brilliance is despite the disability or even the result of it—that subjectivity conditioned the world according to Mehta. His blindness remained his profoundest study.

The controversies—and the fall from grace—engulfed both matters of intellect and character. In many ways, Mehta had perfected, for himself and others, the art of journalistic writing. Elegant but informal. Lucid and sinewy. You could lose your way in the prose but as a compliment to its creator. Yet, not everybody believed he should have trodden everywhere he did. Fly and the Fly-Bottle: Encounters with British Intellectuals (1962) was built on and expanded from his interviews with Oxford philosophers published in 1961. The response to the exercise, back in Oxford, was bloodlust. Isaiah Berlin was polite enough when he wrote to the author about the reaction of his colleagues: 'outraged or indignant'. It was ultimately blamed on, or excused as, the New Yorker's penchant for satire. It was at the New Yorker that Mehta would be attacked and taken to task. By the late 1980s, his colleagues openly questioned the merit of his writing. More serious were the allegations of misogyny. And he was shown the door finally.

Continents of Exile, the collective title of his autobiographical works, is more than an individual's story. It is, of course, the story of everything he had seen without his eyes. Depending on readers, reading on Braille at a time when too few works were available on it, dictating his oral compositions to his assistants, and doing it all over a long life, needed a special kind of strength. Add to that the fact that Mehta never liked a stranger to pity him or a friend or stranger to assist him—physically. The no-walking-stick-no-guide-dog legend of Ved Mehta was actually a clue to his inner workings. Perhaps he became a writer out of defiance. Just as with his descriptions of a world he could not see.