Features | The Wealth Special 2019

Caviar Capitalism

Since the Soviet Union collapsed, caviar has gone from being easily available to being less so; China has become its largest producer in the world; and luxury has gone from being all about global chic to local grunge

Kaveree Bamzai

Kaveree Bamzai

Kaveree Bamzai

18 Oct, 2019

Kaveree Bamzai

18 Oct, 2019

ANYONE WHO grew up in the India of 1990s, when television suddenly unleashed a colourful world of conspicuous consumption upon us, would remember the perma-tanned, perma-smiling Robin Leach introducing each segment of the Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous with the immortal catchphrase: “champagne wishes and caviar dreams”. For a young, innocent India, even one exposed to years of Indo-Soviet friendship, caviar was the God of luxury foods. Caviar on blinis, placed with great attention to detail, was what the rich and famous had as a snack, to be washed down with champagne—all of which in pre-liberalisation India were got through a little bit of that must-make-it-happen jugaad. Caviar bought in the black market from Air India staff where it was served in the first class and champagne (in those days few knew the difference between sparkling wine and champagne) from your friendly neighbourhood bootlegger who got

it from the ‘diplomatic quota’ aka foreign embassies.

But even before that, in the Era Before Google, our minds and stomachs travelled through the movies—and none was more posh than the James Bond ones. From the Dom Perignon with Beluga Bond orders in Thunderball (1965) to the villain who runs a Beluga factory on the Caspian Sea in The World Is Not Enough (1999), caviar has been ever present as our window to the world. And as India has grown in confidence, so has its understanding of food. From craving everything foreign at the dawn of liberalisation in 1991, India has asserted its moffusil moorings, treating black rice from Manipur with as much awe as the timur from Uttarakhand (India’s answer to Sichuan peppercorns) and giving Meghalaya’s turmeric as much respect as the chayote from Tamil Nadu. No longer does the Indian epicure extol the virtues of foreign gourmet foods alone: yes, she can distinguish the salmon roe from the Beluga, but she takes as much pride in exclaiming upon the goodness of makhana or foxnuts from Bihar.

Politics has played some part in this new food world order where the caviar has only a reduced status. Since the Soviet Union collapsed, disintegrating into 15 independent republics, caviar has gone from being easily available to being less so; China has become its largest producer in the world; and luxury has gone from being all about global chic to local grunge. Caviar has always been described as an acquired taste—and one that was difficult to acquire, given that it is essentially the eggs removed from a female sturgeon, carefully passed through a sieve to separate the membrane, and rinsed to remove impurities. The sturgeon, a prehistoric fish available in both sea and fresh water, is now on the endangered list thanks to overfishing. In 1998, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species, started controlling international trade in all sturgeon species. Result: sturgeon farms proliferated and sales of wild caviar fell precipitously.

But increasingly caviar is being farmed, changing the epicentre of the trade to China which now produces 60 per cent of the world’s output. Long-time food columnist, London-based Bruce Palling, who now writes for Reaction.life, a British commentary and news website, says, “I have tried caviar from numerous different places, including Iran, but the very best comes from China—the best is Kaluga Queen’s Schrenckii caviar, a hybrid of the Amur and Kaluga species. I’m not the only admirer. Alain Ducasse already uses this variety at his eponymous three-star Michelin restaurant in Monaco, as do other three-star chefs such as Eric Ripert.”

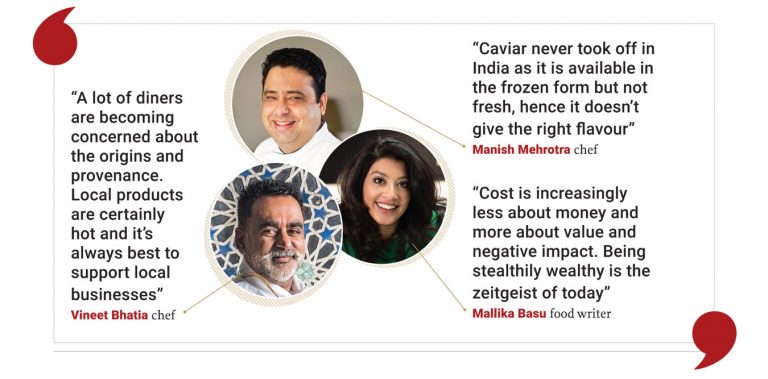

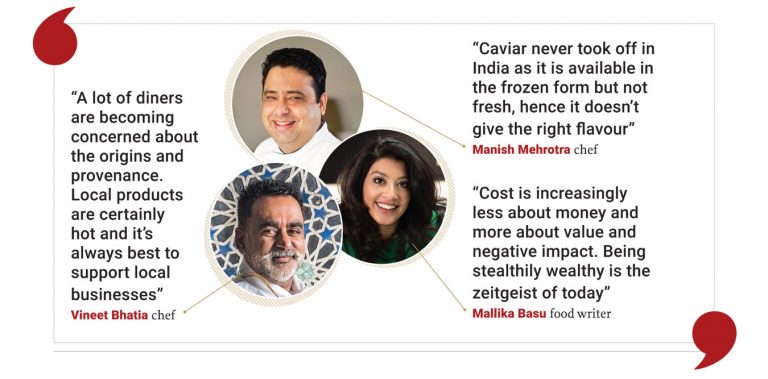

The world has changed in other ways. Environmental concerns are taking over, ensuring consumers look at the carbon footprint of what they buy. As the London-based food writer Mallika Basu puts it: “The trend is driven by conscious consumerism and a heightened awareness of the cost of what is on the plate. Cost is increasingly less about money and more about value and negative impact. Being stealthily wealthy is the zeitgeist of today.”

Indeed, no one wants to be lectured to by Greta Thunberg.

For those with caviar pangs, all you have to do is watch Helen Mirren as the 18th century Prussian-Russian Queen, Catherine the Great, imbibing caviar by the kilo in a new sexed-up HBO mini-series

Share this on

But though caviar may still be the choice of gift when it comes to Hollywood moguls and New York tycoons, in India it has fallen off the map because of a wider variety of luxury foods. The culture of foodhalls, says global chef and the first Indian to get a Michelin star Vineet Bhatia, has ensured an array of unusual foods, from aged balsamic to artisanal cheese, high cacao chocolate to truffles, especially for vegetarians. Healthy grains have also made inroads into the mainstream. Says Bhatia: “A lot of diners are becoming concerned about the origins and provenance. Local products are certainly hot and it’s always best to support local businesses. The likes of foie gras, aged meats and caviar are on the decline not merely in India but also internationally. Vegan, lactose-free and gluten-free are on the rise.”

There is also the question of availability with complicated food import regulations in India. As the National Convener of Forum of Indian Food Importers, Amit Lohani, says, the Department of Animal Husbandry, Dairying and Fisheries is stringent on the issue of sanitary import permits mandated for import of all dairy, meat and seafood. The health certificate compliance is complex even as many European countries find the terms to be the equivalent of non-tariff barriers. So caviar hasn’t quite become popular in India because the supply is erratic and storage is always a problem, even though importers have created a network of cold chains. As food website The Spruce Eats notes, “Caviar is very perishable. An unopened can or jar will stay fresh for up to four weeks, but once opened will only last about three days. The ideal temperature for storing caviar is 28 to 30 F. Most household refrigerators won’t reach this temperature, so the caviar is to be placed in the coldest part, which is the very bottom

drawer. Caviar is not meant to be kept in the freezer. This will destroy its delicate texture. After the jar or can has been opened, the caviar’s exposure to air is minimised by wrapping the container with plastic before storing in the fridge.” Yes, you might as well develop a taste for wine, right?

Manish Mehrotra, Corporate Chef at the Indian Accent restaurants, agrees that caviar never really took off in India as a snob food because “it is available in the frozen form but not fresh, hence it doesn’t give the right flavour”. Add to this the growing pride in regional and provincial ingredients. That’s the future for chefs, he adds, pointing to ingredients that are produced locally but are not easily accessible in the market, such as red ant chutney from Chhattisgarh, fresh hibiscus flowers from Uttarakhand and morels from Jammu.

There is also the rise of free food and superfood. Indians are slowly becoming aware of the importance of food allergies and intolerances, including from lactose, gluten, eggs and nut butters, gluten-free flour, are part of this gambit. The demand for superfood like berries (goji, blueberry, acai and cranberry) for their antioxidant polyphenols, high fibre, prevention and reduction in many chronic diseases has made them part of the global gourmet food chain.

Yet caviar continues to have its admirers everywhere, as do other traditional gourmet food. Palling says, “Caviar is still very much with us but only the farmed varieties, which can be excellent but never as intense and spectacular as the wild.” As for truffles, he says the best are predictably Perigord for black and Alba for white, though black truffles from west Australia are certainly within the ballpark.” There has been no fall in demand for these but in general there has been a growing role for the very best produce, whether blue fin tuna or even asparagus—there is demand for the ultimate examples of vegetables not really because of veganism but more as a result of global communications. “Consumers now have an awareness of where the ultimate produce is grown and they have the ability to either consume it in situ or have it air-freighted to

them,” adds Palling.

Where once there would have been a caviar station at an Indian wedding—with the whole complicated paraphernalia of the kind of crushed ice to serve it on, the spoon and bowl to use and their accompaniments—there is now artisanal water like Voss from Norway, bronze extruded pasta from Italy, bean to bar chocolate made with premium Ecuadorean cocoa, Iberico ham from Spain and Mangalista pork from Hungary. Increasingly though, people are aware of what they are eating and from where. As hotelier Sonu Shivdasani of Soneva once put it, there is little point in going all the way to the Maldives to eat what you can get in your city. At their hotels, they believe in the farm-to-fork philosophy—as far as possible. The days when tourists wanted to travel to exotic countries in air-locked bubbles are about to get over. In their place are the adventurous traveller, ethical eater and responsible international citizen who want intelligent luxury. As for those with caviar pangs, all you have to do is watch Helen Mirren as the 18th century Prussian-Russian Queen, Catherine the Great, imbibing caviar by the kilo in a new sexed-up HBO mini-series.

About The Author

Kaveree Bamzai is an author and a contributing writer with Open

/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/CavierCapitalism1.jpg)

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover-Shubman-Gill-1.jpg)

More Columns

Shubhanshu Shukla Return Date Set For July 14 Open

Rhythm Streets Aditya Mani Jha

Mumbai’s Glazed Memories Shaikh Ayaz