At Home in JNU

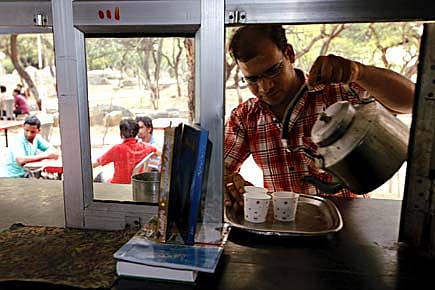

Mohammad Shahzad Ibrahimi took an M.Phil in Urdu from JNU but couldn't part ways with his alma mater. He set up an eatery in the campus

Saahebaan, meherbaan, kadardaan. Walekum-as-salaam, namaste aur good morning. I am your host, Mohammad Shahzad Ibrahimi, but please call me 'Mamu'. Thank you for giving me the opportunity to speak. What I am can be summed up in one word. It consists of only three letters: JNU. The 'J', the 'N' and the 'U' carry the story of my life. So much can be told in so little.

If you're at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) in Delhi any time, do ask around for 'Mamu' or 'Mamu ka Dhaba'. You will get instant directions to where I am; a history of who I am; a double-quick summary of what I did. Let me change that. What all I did. I'm not bragging. Just ask around. I won't be surprised if you are surprised.

I know when people talk to me, they must think it odd. After all, who ducks an academic career, gives up being a news anchor on a TV show and returns to one's alma mater to open an eating joint? But that's me. I'll tell you why I am who I am.

Normal people get into relationships with other normal people. I forged one with a whole university campus! From my very first day way back in 1993, I knew I was in love with JNU. It was green, young and welcoming. I became friends with students from all corners of India, and some from abroad. The student-teacher equation was entirely unlike what I had known. Here we applied rangoli on our teachers' faces during Holi. Some professors called you home for Eid. Others came to the hostels for roza. Many would attend hostel mushairas. All this was a far cry from my native Bihar.

Rule Americana

16 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 54

Living with Trump's Imperium

When I was in school, at a madarssa in Arihari village in Sheikhpura district of Bihar, I hated studies. The only things I showed interest in was Urdu and food. Once in Class XII, the mess in-charge of our hostel vanished. I gathered some of my school friends and made two kinds of vegetables, yellow dal and chapatis for 25 people. My school teachers were amazed.

I obsessed over onion and tomato salads. I cut them in zigzag fashion; not the straightforward chop. The art of cutting vegetables fascinated me. It was the key to making a good dish. With brinjal, for example, the shape of the cut can make it a pickle, a fry or a bharta. Even before the work of spices, the first skill is to master the cut.

Also, food has to look good to be liked. The image of the item has to win over the potential consumer. Having run an eatery for five years now, I can tell you that eating is an activity that opens up the psyche of the eater. A hungry man is the most dangerous and vulnerable creature in the world. Feed him well or he will feed on you.

After school, I went to college in Patna University. Over a meal one day, some of my seniors told me to apply for JNU. I prepared hard to write the competitive entrance exams and in two months' time, landed up at Room 214 in Kaveri Hostel in JNU. The year was 1993.

That was a heady time in JNU. A Naxalite student union leader went away to fight for the tribals in Bihar and never came back. In the post-Babri demolition period, JNU became very tense. Without much thought, I got into student politics. I joined the Students Federation of India (SFI), only to leave it soon. My public life in JNU took over. In no time, I jumped into theatre. I went from performing in music shows, spouting Urdu shaiyari to fronting plays. The fun began when I participated in the chaat sammelan. This is a stand-up comedy event in JNU and Delhi University, where the most entertaining and time-consuming speaker wins. I won it five times in a row. My identity changed from Mohammad Shahzad Ibrahimi to 'Mamu'.

All this was total masti. After MA and MPhil in Urdu, I joined the mass media course in JNU. But by the end of my MPhil and six years of fun, the idyll of JNU and the reality of the outside world hit home. Like many other JNU students who stayed on for a long time, it was easy to get flustered. You were 24-25 years old and without a job. JNU promised you a good education, but the hunt for work had to be one's own. A lot of my friends turned bitter about JNU overnight. They even began abusing and cursing, saying that the years in JNU didn't get them a job. My question to them was: when did JNU ever assure you of employment? It guaranteed you only a good degree. Never did it claim to build you your future. You took the education and charted your own course in the outside world.

By the end of MA, though, I had fallen in love. My partner (now my wife) was Hindu. Like in many of the love stories at JNU, religion became a cause for domestic tension. Opposing both our parents, we secretly married, on campus, and moved to the married students' quarters. My wife managed to obtain a lecturership at a college in DU.

E-TV from Andhra Pradesh had just started its Urdu news channel from Hyderabad. After six years at JNU, I left for Hyderabad. I was in for a jolt. Though it was exciting, TV anchoring had its petty problems. Language was one of those. Strange, even if the language is the same (in this case, Urdu), there is always fodder to divide people. One of the unfortunate things about the decline of Urdu is that every Urdu speaker thinks his zabaan is the best. The media world was full of such types. Little did I know that the pronunciation of a word would change the course of my life.

In Hyderabadi Urdu, the word lekin ('if', or 'but') is intoned as liakin. When I spoke on television, I'd use the north Indian pronunciation, which is proper Urdu. But my boss wanted to change the way I spoke. Among other things, the North-South divide cheesed me off. In a year's time, I got myself transferred to Delhi. I was back with my wife and child.

In the Delhi office, there was more politics. I also noticed there were hierarchies everywhere—something I discovered I could not handle. Once you became a senior after years of experience in the media, you actually stopped working. In Delhi, all the Urdu-speaking seniors sat around sipping tea, chewing paan, and giving gyaan. With them around, the tobacco and liquor industries would never incur losses. Here too, the Urdu divide came in. I was from Bihar, so my 'Bihari Urdu' became inferior in front of these Delhiwallahs who spoke 'real Urdu'. I was now done with this lot.

So one day, I quit. My family, my wife and my folks were shocked again. For months my wife took charge of running the house. I spent days in deep thought. During that time, I made up my mind to only pursue my real passion: food. I asked my professors about being given a canteen to manage. They were taken aback, but once they were convinced of my self-confidence, they allowed me to run a canteen in JNU. It did well. Later, I asked the JNU management for my own canteen to be allotted on campus. They chose the area behind the main administrative block.

My second career took off. 'Mamu Ka Dhaba' began in 2003. Bihari thaali became my specialty. Now I rent a flat outside campus, but live and work here for all practical purposes. JNU is my home. Even my postal mail comes here. Sixteen years gone. More to come and go.

Guftagoo ke liye shukriya. Khuda hafiz.