The Truth About Aurangzeb

FANATICS ALWAYS HAVE their supporters and defenders. Long after he purged millions, Stalin continues to be venerated by certain groups. The further we travel in the past, the barbarities get whitewashed, or exaggerated, and fantasies overlay the real world. One such fantasy surrounds the last powerful Mughal emperor, Aurangzeb. While many in India view Aurangzeb's rule as a dark period marked with unparalleled iconoclasm, a new narrative is emerging—a narrative that questions whether Aurangzeb was a bigot. In normal times, the insurmountable primary evidence—and the ruins in front of our eyes—should have put a closure to this debate. But the luxury of normalcy is denied to us. An unfortunate casualty of this new narrative is Indian secularism. By situating the "Aurangzeb: bigot or not" debate in the larger Hindu-Muslim context of contemporary politics, such a narrative expects present-day Muslims to defend—or even embrace—Aurangzeb and his atrocities. This false dichotomy denies Indian Muslims the freedom to reject Aurangzeb without their commitment to their identity as Muslims being questioned.

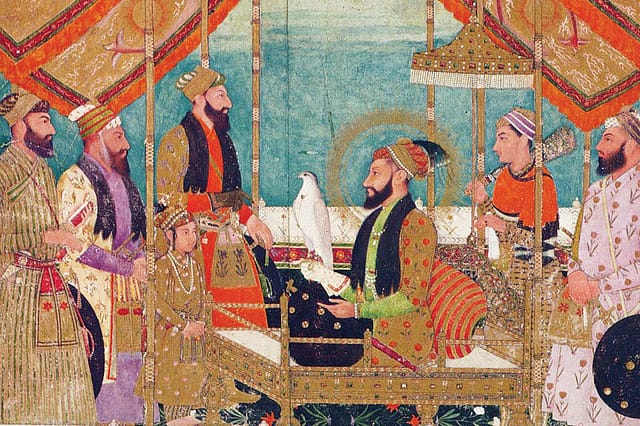

This essay is based on contemporary and original sources. It does not reflect the authors' personal opinions. History is a constantly evolving process. It is, therefore, quite reasonable to explore again whether Aurangzeb was indeed a religious fanatic. Aurangzeb was a unique emperor. In his long life of 89 years, he ruled the vast Mughal Empire for nearly 50. He outlived Chhatrapati Shivaji and Sambhaji, brought down the reign of Adil Shah, crushed many rebels in the north. At the age of 85—an age medieval kings rarely reached—he was on the battlefield leading from the front. But, just like his valour, his fanaticism accompanied him to his grave. The military victories proved to be pyrrhic in the end.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

The line of enquiry arguing that Aurangzeb was not a religious fanatic relies on the work of Richard M Eaton. Recently, a few other 'academics' have packaged an old wine in a new bottle. But we will confine ourselves to the original source and avoid sensationalists.

Eaton and a few other researchers' arguments that question the colloquial wisdom surrounding Aurangzeb make the following three points: First, while Aurangzeb did demolish temples, political calculations, and not religious iconoclasm was the main motivator in his temple desecrations. Second, the number of temples claimed to have been demolished by him is exaggerated. Moreover, Aurangzeb seems to have assigned madad-i-maash (a reward effectively amounting to cash and/or foodgrain) to even a few Hindu temples. Third, a number of 19th and 20th-century colonial historians who have written about Aurangzeb could possibly have a motive of denigrating Mughal rule in the eyes of the Hindu population to legitimise British rule.

Since the three are closely linked, let us begin by looking into the first point. In the process, we would have settled the second, and the third points as well. Fortunately, there is abundant material available on Aurangzeb's reign. But we will primarily rely on the court history, the newsletters of the Mughal court, Aurangzeb's farmans (imperial orders), Maasir-i-Alamgiri by Saqi Mustaid Khan, and a few other primary sources so that the 'colonial historians' card is not invoked all and sundry. Of course, there is a disturbing tendency to label even Sir Jadunath Sarkar as a colonial apologist, but we do not believe that such arguments merit a rebuttal.

ONE OF THE most prominent arguments that Eaton makes in support of the 'Political Motives Theory' (PMT henceforth) is the story of the famous Kashi-Vishwanath temple of Varanasi that Aurangzeb demolished in 1669 to build the Gyanvapi mosque on the site of the temple. To quote Eaton: "In 1669, there arose a rebellion in Benares among landholders, some of whom were suspected of having helped Shivaji, who was Aurangzeb's arch enemy, escape from imperial detention. It was also believed that Shivaji's escape had been initially facilitated by Jai Singh, the great-grandson of Raja Man Singh, who almost certainly built Benares's great Visvanath temple. It was against this background that the emperor ordered the destruction of that temple in September, 1669 (no 69)."

While interesting, this narrative does not reconcile with the available evidence. For one, no primary source that mentions a link between any rebellion and the demolition of the Kashi-Vishwanath temple is offered. Indeed, the famous official history of Aurangzeb, the Maasir-i-Alamgiri, mentions a rebellion in Agra in November 1669. But the argument that Aurangzeb demolished a temple in Varanasi to crush rebels in Agra seems tenuous given the distance between the two cities (600 kilometres). Even if one were to accept such an implausible scenario, another obstacle awaits. The rebellion in Agra seems to have occurred after the demolition of the Kashi-Vishwanath temple. In fact, the link between the rebels and the demolition of Kashi-Vishwanath seems more illusory than evidential if one looks at how it is described in Maasir-i-Alamgiri (translated by Sir Jadunath Sarkar, page 55):

"On Thursday, the 2nd September 1669/15th Rabi S, Muza Mukarram Khan Safavi died of severe fever.

It was reported that, according to the Emperor's command, his officers had demolished the temple of Viswanath at Kashi.

On Saturday, the 18th September/2nd Jamad A…"

Notice how insignificant this event is in the eyes of the chronicler—the line before or after makes no mention of this demolition. In other words, by their own official account, this seems to be a very routine activity.

Therefore, ascribing a political motive to Aurangzeb's action of destroying a temple in Kashi is not supported by any evidence as Aurangzeb himself does not seem to have expressed anything remotely suggestive of this. Yet, if we run along with this story further, the PMT runs into more hurdles. Eaton claims that Jai Singh was thought to have abetted Shivaji's escape. It was, in fact, Ram Singh, Jai Singh's son, whom Aurangzeb suspected to have helped Shivaji. Taking this inaccuracy for a casual oversight, here is a sequence of events: First, Shivaji escaped from captivity despite Aurangzeb's heavy security to script an extraordinary episode in the Indian renaissance—the escape from Agra—on August 17th, 1666. Second, since Ram Singh had given his personal guarantee regarding Shivaji's conduct in Agra, Aurangzeb suspects Ram Singh for helping Shivaji escape. Third, this suspicion possibly led (although the available evidence suggests otherwise) to his falling out of Aurangzeb's favour. Meanwhile, Jai Singh dies in 1667, and Ram Singh becomes the new king of Amber.

That is, if Eaton's version is to be believed for a moment, Aurangzeb punished Ram Singh's supposed treachery by destroying the Kashi-Vishwanath temple a full three years after his 'crime'. For a ruler celebrated for his celerity, this seems oddly sluggish. Yet, accepting this tardiness for administrative delays, a new challenge appears. Raja Jai Singh died in September 1667, and there is a record of several face-to-face and warm dialogues between Ram Singh and Aurangzeb (Akhbarat dated September 17th, 1667, The Military Dispatches of a Seventeenth Century Indian General, page 41, Jagadish Narayan Sarkar). After Jai Singh's death, Ram Singh was coronated as the new king in 1667, and the Emperor himself blessed the occasion by attending the ceremony (Maasir-i-Alamgiri, page 41). Maasir-i-Alamgiri says: "The emperor cherished his (Jai Singh) son Kumar Ram Singh, who had so long been under punishment, by giving the title of Raja and many favours."

If one were to run with the argument of Aurangzeb punishing Ram Singh's transgressions, it reads as follows: Ram Singh helps Shivaji escape in 1666. In 1667, Aurangzeb forgives him by attending his coronation. Then, two years later, Aurangzeb decides to punish Ram Singh again by destroying temples not in the city where Ram Singh lives, but in a totally different city.

It is a mystery why a medieval emperor ruling large parts of India would think of such convoluted punishments. It is certainly a worthwhile scholarly endeavour to explore the political motives behind Aurangzeb's demolitions. However, given what we know, this line of enquiry does not seem to stand on any material evidence.

TO HIS CREDIT, Eaton seems to be aware of the tenuous logic in the Kashi-Vishwanath demolition discussed earlier, especially because of a famous diktat by Aurangzeb ordering demolition. He offers a new "translation" of this famous order by Aurangzeb. Here is Eaton's translation (emphasis added): "Orders respecting Islamic affairs were issued to the governors of all the provinces that the schools and places of worship of the irreligious be subject to demolition and that with the utmost urgency the manner of teaching and the public practices of the sects of these misbelievers be suppressed."

And here is Sir Jadunath Sarkar's translation of the same: "His majesty, eager to establish Islam, issued orders to the governors of all the provinces to demolish the schools and temples of the infidels and with the utmost urgency put down the teachings and the public practice of the religion of these misbelievers. (Maasir-i-Alamgiri, page 52)"

Eaton argues that the phrase "subject to demolition" suggests an administrative enquiry of sorts to determine whether a place should be demolished or not. First, this conspicuous "difference" in translation neither matches the original text nor translations of Maasir-i-Alamgiri in other languages. For instance, besides the translation by Jadunath Sarkar, there is also a translation done by Lt Perkins that appears in Elliot and Dowson's The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians (Volume VII, page 184): "The "Director of the Faith" consequently issued orders to all the governors of provinces to destroy with a willing hand the schools and temples of the infidels…" (emphasis added).

Recently, Maasir-i-Alamgiri was translated into Marathi by Rohit Sahasrabudhe and, unsurprisingly, that too has no reference to the conspicuously benign "subject to demolition." Munsi Devi Prasad has translated the text of Maasir-i-Alamgiri to Hindi as Aurangzebnama (Volume II, pages 11-12). It also says that Aurangzeb issued an order to demolish the temples, that is, not subject to demolition but rather all-and-sundry demolition. While one of us knows Persian, we wanted to be doubly sure. Therefore, we consulted another independent expert of Persian, who too agreed with Sarkar's translation and not Eaton's. Therefore, in summary, the suggestive difference in translation seems intriguing to put it politely. In fact, the following text that precedes the order leaves little room for ambiguity: "The lord Cherisher of the Faith learnt that in the provinces of Tatta, Multan and especially at Benares, the Barhman misbelievers used to teach their false books in their established schools, and that admirers and students both Hindu and Muslim, used to come from great distances to these misguided men in order to acquire this vile learning."

Eaton turns this into a question by saying, "We do not know what sort of teaching or 'false books' were involved here, or why both Muslims and Hindus were attracted to them, though these are intriguing questions."

We do not believe, especially so for Eaton, that it was so difficult to guess what 'false books' Brahmins would be teaching in Varanasi in the 17th century. Bear in mind, here was a ruler whose own brother (Dara Shukoh, whom he beheaded and served the head to his father) was seduced into 'false books' (Upanishads). Finally, why would Hindus and Muslims be attracted to these 'false books' if they offered nothing useful to the students? But that is, perhaps, a matter for another day.

IT IS A BIT unfortunate that we have to go to this length to establish what is blindingly obvious—that Aurangzeb was an intolerant ruler. The signs of his fanaticism were visible very early in his life. For instance, in 1644 (when he was a prince posted in Gujarat as a viceroy), he converted a newly built temple of Chintaman into a mosque (Mirat-i-Ahmadi, page 222). He also, reportedly, desecrated the temple by slaughtering a cow in it (source: Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency (Volume I, Part I, page 280).

Aurangzeb began his career as a bigot. And, just like his bravery—being on a battlefield in the sweltering heat of Sahyadri at the age of 86 is no small achievement—his savagery never left him, even in old age. Age often mellows people. But not Aurangzeb. In 1698, at 80, Aurangzeb deputed Hamid-ud-din Khan Bahadur to destroy the temple of Bijapur and build a mosque (History of Aurangzib, Volume III, page 285, Jadunath Sarkar). An elaborate—but not exhaustive—list of temples destroyed by Aurangzeb (which includes some famous temples like the Somnath temple, the Kashi-Vishwanath temple, the temple in Mathura, to even tiny temples like the Khandoba temple in Aurangabad near Satara, and hundreds of temples in Rajputana) is available in primary sources such as Maasir-i-Alamgiri and Newsletters of the Mughal Court. Somewhat mysteriously, most of these desecrations fail to make it to Eaton's database despite irrefutable evidence.

In a grotesque display of his intolerance, after he destroyed the Dehra of Keshav Rai in Mathura in 1670, he had the idols brought to Agra and buried under the steps of the "mosque of the Begam Sahab", in order to be continuously trodden upon (Maasir-i-Alamgiri, page 60). Eaton attempts to link this demolition also to the Agra rebellion. Evidence in support of this claim remains elusive, unfortunately. Just because there was a rebellion around Agra in 1669 does not mean every act of desecration is linked to the rebellion unless one finds concrete evidence to the effect. Beyond conjectures, there is none. At 85, Aurangzeb demolished the temple of Vithoba in Pandharpur (Mogal Darbarchi Batmipatre, Setu Madhavrao Pagadi, Volume III, page 472). He wanted to demolish the temple of Mahalaxmi in Kolhapur (ibid, Volume II, page 86). He destroyed the temples in the villages of the Deccan where he went and erected mosques on those lands. These references have come in the Mughal court newsletters. Aurangzeb also demolished temples on several forts in Maharashtra, such as the temples on Vasantgad and Panhala. The foundation of the mosque at Vasantgad was laid by Aurangzeb with his own hands (ibid, Volume I, page 86). As a medieval king engaged in battles on different fronts, we can always find a battle that can be forcefully connected to most of these temple desecrations. To avoid such spurious links, the only acceptable proof of a political motive should be if either the emperor or his court mentions such a motive in their proceedings or if the sequence of events leaves little room for ambiguity. Otherwise, like us, future researchers would need to spend tremendous energy countering castles in the air.

The list of his religious excesses is so astonishingly long that an article can never do it justice. Besides demolishing temples and imposing Jaziya (a discriminatory tax on Hindus), he even sought to curb Diwali celebrations by ordering them to be held only under some restraints, and outside bazaars.

GIVEN THE INSURMOUNTABLE evidence—none of which is new—it seems rather difficult to adopt a favourable view of the PMT. It is nobody's case that every temple demolition by Aurangzeb was solely a religiously motivated act. But the position by Eaton and a few others is diametrically opposite. Their argument is that almost every act of demolition has a political context. It is reasonable to assume that they would offer the strongest available evidence to buttress this theory. That evidence is the Ram Singh story and the 'different' translation of Aurangzeb's order. As we have seen, the Ram Singh story is more of a conjecture not supported by facts, and the translation seems to conspicuously disagree with every single other version.

Finally, the claim by Eaton (2000) that temples were considered politically active, and hence vulnerable to demolition as per the "customary rules of Indian politics" is again more a surmise than evidential. For one, "politically active" is a vague term that can encapsulate all or no temples. More importantly, as mentioned before, in the case of Kashi-Vishwanath, Aurangzeb (and his predecessors) destroyed several temples in their own kingdom, both in times of peace and war.

THIS BRINGS US to the second and the third points in the opening part of this essay. Just to remind the reader, the two points are that the claims about the precise numbers of temples demolished are vastly exaggerated and that a number of historians during the British era had a political motive to justify British rule by disparaging Mughal rulers. On exaggerations, for a moment, let us even suppose that claims such as "…the Emperor went to view Chitor; by his order sixty-three temples of the place were destroyed" (Maasir-i-Alamgiri, page 117) are exaggerated. It is an admirable goal to have a more precise estimate of the temples that Aurangzeb had desecrated. But a lower bound on this number is not particularly hard to obtain by examining the primary sources, especially since several sites of temples mentioned to have been destroyed are publicly accessible. Therefore, to discredit the claims of Aurangzeb's bigotry by pointing out a few inaccuracies or exaggerations is counterproductive. Moreover, Eaton himself cites instances of court poets trying to impress the emperor by talking of his glories of temple desecrations by, supposedly, exaggerating the number of temples destroyed. Why would a poet impress the emperor by fabricating instances of temple desecrations, if the emperor did not revel in such desecrations? An Occam's razor explanation—that temples were demolished mercilessly, outrightly for religious motives—does not pose more questions than answers.

Finally, on the charge of colonial historians, a historian is worth only the evidence (s)he presents. It is entirely irrelevant whether Sir Jadunath Sarkar or Sir HM Elliot were colonialists or Hindu nationalists. For example, a famous Italian traveller, Niccolao Manucci, who spent most of his life in India, has the following to say: "The latter [Aurangzeb], rid of a rajah [Raja Jai Singh] whose influence might have been dangerous to his kingdom, declared that very hour an open war against Hinduism.

He sent orders at once for the destruction of the fine temple called Lalta, in the neighbourhood of Dihli. He also ordered every viceroy and governor to destroy all the temples within his jurisdiction." (Storia do Mogor, Volume II, page 154)

Or take the instance of the following correspondence between two Englishmen in 1670: "The archrebel Sevagee [Shivaji] is againe engaged in armes against Orangsha [Aurangzeb], who, out of a blinde zeale for reformation, hath demolished many of the Gentues temples and forceth many to turne Musslemins" (Letter from Gary to Lord Arlington, 23rd January 1670, English Records on Shivaji, Volume I, page 178.)

We wonder why an Italian-born tourist or a 17th century officer stationed in Bombay would connive with the yet-to-be-born colonialists to malign Aurangzeb in order to justify British rule over India that was to be established almost 150 years later. It is, after all, a mystery why a motley crew of colonialists, Hindu nationalists, contemporary historians from Aurangzeb's darbar to Maratha historians, travellers like Niccolao Manucci, and employees of the East India Company—a group of people separated by race, time and geography—would conspire to call Aurangzeb a bigot who outdid his predecessors.

AURANGZEB'S DEFENDERS often cite instances of Hindus that occupied prominent positions in his reign as evidence of his tolerance, or some instances of his donations to temples. It is unclear whether this is dark humour or a serious defence, for one could, by similar logic, deny the Holocaust by pointing to Jews in Hitler's army. The idea that a medieval ruler would rule over such a vast land inhabited by infidels—as Aurangzeb called them—without placating a section of Hindus sounds rather odd. One famous story of Aurangzeb's policy of religious tolerance is his order early in his career prohibiting destroying temples and building new temples in Varanasi (Aurangzeb's farman to Abul Hasan dated February 28th, 1659, preserved at Bharat Kala Bhawan, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi). Remarkably—or understandably—Eaton and others seem to have missed the obvious political angle behind this order.

Remember that the year is 1659, shortly after Aurangzeb seized the Mughal throne by winning two battles with Dara Shukoh and one battle with Shuja. The battle with Shuja took place on January 5th, 1659 at Khajua. Shuja was defeated in this battle and fled to Varanasi (Banaras). To ensure that the Hindus of Varanasi did not join hands with Shuja, Aurangzeb issued a farman to Abul Hasan, the fauzdar of Varanasi on February 28th, 1659, to not demolish the old temples. Sir Jadunath Sarkar says the following about this farman: "farman had been issued during Aurangzeb's struggle with Shuja just by way of a political move to win for the time being the good will and co-operation of the Hindus for capturing Shuja and had nothing to do with his spirit of toleration" (Life and Letters of Sir Jadunath Sarkar by HR Gupta, Punjab University, Hoshiarpur, Volume I, page 60, 1957).

It is important to note that, while directing the fauzdar, Aurangzeb also ordered not to build new temples. Why would a tolerant king prohibit the building of new temples? Evidently, this farman, rather than being proof of Aurangzeb's tolerance, is a testament to his political acumen that let him curb his fanatical instincts.

A reader may rightly question whether we are conveniently using the political context to suit our narrative. But notice how the dates of Aurangzeb's battle with Shuja and the following farman are not even two months apart. The combined evidence of the dates, the contemporary evidence and the commentary by Sir Jadunath Sarkar overwhelmingly suggest a political motive. Compare this evidence with the Ram Singh story where the "crime" and the "punishment" are separated by three years, with a period of bonhomie in between.

We are reminded of what Jonathan Swift wrote in his seminal essay, 'Political Lying': "falsehood flies and the truth comes limping after it, so that when men come to be undeceived it is too late." We are hopeful that it is not too late.

(The authors would like to thank Rajendra Joshi and Niranjan Rajadhyaksha for their valuable inputs to the piece)