In Search of the Orient

It no longer exists. Instead, we have the global South

Carlo Pizzati

Carlo Pizzati

Carlo Pizzati

Carlo Pizzati

|

14 Apr, 2023

|

14 Apr, 2023

/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Orient1.jpg)

The Snake Charmer, circa 1879, an iconic Orientalist painting by Jean-Léon Gérôme made famous by the cover of Edward Said’s 1978 book Orientalism (Photo: Alamy)

WHEN YOU’RE LOST, when you don’t know where the orient is, when you can’t figure out where’s the east, you are disoriented. A term commonly used in many European languages to establish your position at any given moment, synonymous with finding your bearings, is the verb “to orient” yourself. The reflexive form of “to orient” refers to establishing your position in relation to the rising sun.

In order to see things in a clearer light, especially in the morning hours, the ancient Greeks and Romans “oriented” their temples, building their main façades facing east. This is where the concept of orientation emerged in many languages as a process aimed at facilitating understanding and self-awareness—knowing where things are is a good start in making you comprehend what they are.

This brief etymological excursion may help explain why, hidden among the folds of our language, for centuries the so-called Western world has been feeling the need to understand what has been called the “Orient”. Today, there appears to be a renewed pressing need, in Europe and in America, to draw a conceptual map for the purpose of reorientation, asking: “How can the old West face the new Orient?”

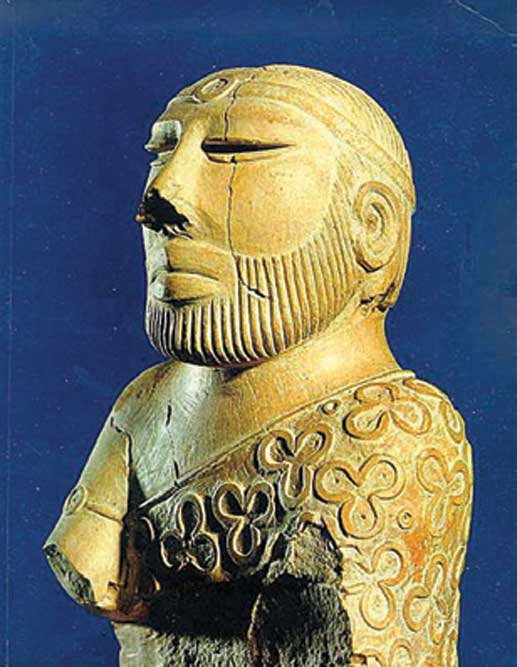

Ironically, this way of posing the question, inherent in our very own idiom, does not help us understand, or “orient” ourselves. Asian civilisation is not new; it is ancient. The so-called “new Orient” draws many of its strengths and a lot of its cohesion precisely from this antique identity, more so than from any novel element. Some North Asian countries are inspired by the collectivism derived from Confucian philosophy. Elsewhere, Hindu philosophy nourishes the subcontinent’s propulsive force as it pursues its dharma. Many other parts of Asia are driven by a familial, dynastic, religious, and cultural traditionalism that spans both the north and south of this massive continent.

The dichotomous split between the “West and the Orient” is a historical and instrumental laziness of European and Anglo- Saxon cultures (by which we mean the British Isles, North America without Mexico, and Australasia)—this is what today we call the “Global North” (adding Japan). Asia, Africa, and Latin America have come to be known as the “Global South”, replacing the demeaning hierarchy of the term “Third World” or the jarring label of “Developing Countries”, where so-called “development” is evaluated through the Euro-Anglo-Saxon perspective of an economic progress which does not necessarily bring a developed quality of life all around. Often, the sheer context of juxtaposing societies in terms of a unilateral idea of “development” was conceived with the purpose of establishing a hierarchy necessary to justify the conquest of colonisation—just like the Jesuits who argued that indigenous populations where “potentially like us” (Caucasian Christians) because they only needed to convert and be educated into the Western culture in order to “develop”.

In this scenario, within the bellicose regional context created since 2014, Russia positions itself as a “Eurasian nation”, in a bridge that explains its role as a powerful aggregator, determined to bring Europe back to its geographic reality as the farthest extension of an uninterrupted territory that starts at the border with Alaska and ends in Gibraltar.

New ‘Orient’ and old West. Nothing could be more misguided than this view. The ‘Orient’ is not new. The strengthening of Asia’s role represents a return to how things were historically in the balance of world powers, not a novelty. But then, again, Orient in relation to which cardinal point? What is the centre of this West and this East?

All this must be understood in order to free ourselves from a dangerous mental constraint built on the cloying exoticism of the word “Orient”, and its adjective “Oriental”, perceived today as a racist insult by minorities of Asian origin living in Anglo-Saxon countries. Perhaps this reasoning can also serve to deconstruct the idea of the West, a term that defines an even more elusive and amorphous reality.

Defining “others” is always easier than defining oneself. What is the West, today? Is it woke? Does it hate immigrants? Is it democratic? Or does it adore the charisma of one strong person at the helm? Many Europeans were stunned by the divisiveness of Brexit; dumbfounded by the deep isolationism of the Trump presidency; split to the east by flirtations with Putinism; and in the process of examining their conscience about the inhumanity of Western colonialism that has enriched the global North for the past five centuries.

New “Orient” and old West. Nothing could be more misguided than this view. The “Orient” is not new. The strengthening of Asia’s role represents a return to how things were historically in the balance of world powers, not a novelty. But then, again, “Orient” in relation to which cardinal point? What is the centre of this West and this East? The Middle East of Jerusalem? Even this would be a Judeo-Christian viewpoint that reflects a cultural limit, a geometric perspective not shared by the whole world.

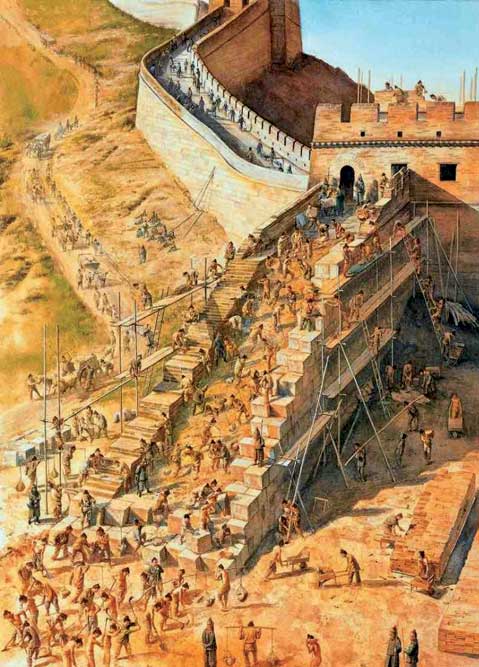

The West is not old. European culture is younger than Indian and Chinese culture. Anthropologically speaking, Europeans are not the oldest either, as humans evolved in Africa. The first humans appeared in Africa from 250,000 to 300,000 years ago. In Asia, humans popped up about 50,000 years ago. People arrived in Europe only 43,000 years ago. In this sense, Europe is the youngest continent, the one most recently populated. Overall, the four oldest civilisations of the world sprouted in Mesopotamia, Egypt, the Indus Valley and in China. None of them developed in Europe. Caucasians are merely a result of a vitamin-D seeking depigmentation trend (blond hair is an effect of that phenomenon), when an overgrown human population was forced to move from Africa and the so-called Middle East to areas where the sun hides for long, cold periods in the winter. The same white America, the Anglo-Saxon and Protestant one, the one that rules, makes laws, and influences the economy, the one that has managed power within the US from the American Revolution until today, is a historically recent phenomenon, the child of an adolescent (in the context of ancient religions) Protestantism and of a pre-pubescent (in the context of global philosophies) Enlightenment.

The point is that what we call the West, that is, the global North, is not old. But it is ageing. Most worryingly, for so-called Westerners themselves, it feels old. Its culture is increasingly outdated. The global North is old in the sense that it is full of elderly people, tortured by ailments and diseases while remaining combative, although inevitably less productive than when they were younger. Nostalgic old people full of old ideas, many of whom are resistant and inflexible to change.

The global North has been feeling a cultural fatigue for decades, clinging to the sound principles of ancient democracy (increasingly taking on the features of an oligarchy), a revival of civil rights (after violating them in most of the world with colonisation), and the fluctuating mix of freedom and equality that is dispensed in parliamentary settings, where elected officials should legislate to shape these two moulding forces of society. In purely demographic terms, it is appropriate to speak of a young and new Asia and an old and worn-out Europe allied with North America and Australasia. A young South and an old North of the globe.

This in itself should explain why migration benefits everyone, as it often has in history. It would now be desirable for the global North to export some of its retirees to the warm climates of less expensive Thailand, Malaysia, India, and Indonesia, while the global South could facilitate an organised flow to the West of young people who want to work and contribute with their labour to pay for pensions in the North. We should honestly take note of it and structure this system, avoiding the horrors at the borders between the global North and South, for which Europe, America and Australia will be remembered infamously in the near future.

The four oldest civilisations sprouted in Mesopotamia, Egypt, the Indus Valley and in China. Caucasians are merely a result of a Vitamin-d seeking depigmentation trend when an overgrown population was forced to move from Africa and the so-called Middle East to areas where the sun hides for long, cold periods in the winter

Let us no longer speak of the Orient and the West. Let us speak of Asia, Europe, Africa, and North and South America, if we must. This is a first step towards a more equitable multipolar world, by being more precise and freer from dated views of the world. And let us look at the changes that have brought us to the current re-alignment. The four phases of Asian development from the post-war period to today are well known. It all begins with the Japanese miracle that rises from the post-atomic ashes of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and rebuilds its economy and industries to peak in the late 1980s, followed by the second phase, that of the Asian Tigers, led by South Korea which, with its engineering and hard work based on family dynamics, also creates a stronger economic regional context around Japan, paving the way in the 1990s for China’s turn towards a form of communist-capitalism, an oxymoron on which its success still relies (communists at home, capitalists in the world), which now opens the way to the fourth phase, that of Southeast Asia led by India, the fifth global economic power, with the fastest growing economy in the world, along with Vietnam and the Philippines, chased by Indonesia’s gallop.

Yet for more than thirty years, many Europeans and Anglo-Saxons have obsessively focused mostly on the Chinese threat. That’s where the business opportunities are, guarded by a growing military power. This is why, thinking in Western terms, many harbour the fear that China aims to dethrone America at the head of the world empire, so to speak. However, China preaches the desire to participate (although as first among equals) in a multipolar world where democracy prevails among countries, and not the domination of a superpower as in the bloc to the West, with America as the world’s policeman and the others who must follow suit. In other words, full democracy in relations between nations that are often experiencing varying degrees of challenges in their internal democratic process.

THUS, WE ONCE AGAIN get distracted by a paradigm that may not unfold as we imagine. The Western fear of an unchecked China substituting the US as the world’s super-cop may be outdated. This paradigm does not consider the future that lies in Southeast Asia where the next market is. China may have already reached a peak, not only demographically but also in aggressive economic expansion. It’s difficult to envision exponential growth in China, given the spikes seen from the 1990s to the present.

Today, China is understandably focused on nurturing its domestic market—selling Chinese products to Chinese people to enrich its own economy while reducing dependence on exports, where in any case it remains strong. The Belt and Road initiative increasingly appears to be a costly attempt to consolidate markets, an investment that, for now, has not yielded succulent fruits. Perhaps it will yield them in Africa, but in Asia, for now, it’s an investment that hasn’t returned as much as hoped. Not to say it won’t, but it hasn’t.

For more than 30 years, many Europeans and Anglo-Saxons have focused mostly on the Chinese threat. That’s where the business opportunities are, guarded by a growing military power. This is why many harbour the fear that China aims to dethrone America at the head of the world empire

Today, many fear that the real global conflict will not ignite in Ukraine but in the Indo-Pacific, where weapons are accumulating, with India being one of the largest importers and now working on becoming a serious arms manufacturer, with the collaboration of the European and Anglo-Saxon defence industry. But this also risks becoming an inevitable game of détente similar to that of the Cold War. A huge business for all arms producers crowded around Taiwan, as if it were the new Berlin Wall of this new Cold War between the global North, led by the US, and the global South, which is proposing a multipolar realignment of the BRICS (the intergovernmental organisation of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) which could expand to Shiite Iran and Sunni Saudi Arabia, countries that, thanks to Xi Jinping, are shaking hands for the first time in many years, even though they are engaged in a prolonged proxy war in Yemen. The foundations of the multipolar world could thus soon be called BRICSIA.

But it’s not so simple. The reality is that the players on the geopolitical chessboard operate in a more complex manner. For decades, China and India have had military tensions in the Himalayas. While China supports Pakistan, another nuclear enemy of India, Moscow seems to support Delhi, selling arms to India and supporting it at the United Nations (UN). China keeps under its protective wing the feisty North Korea, where Kim Jong-un’s missile tests and nuclear threat keep playing a disturbing role with Japan and with the US military presence in the region. Iran and Saudi Arabia are at war in Yemen. And while China weaves its alliances in this increasingly complicated network, its naval fleet provokes pro-Western nations like Marcos’ Philippines, pushing them towards allies in the strategic Quad pact, which includes Australia, Japan, the US, and India. India serves as the pivot in both the global South’s BRICS and the global North’s Quad. It manages to navigate the centre of this supposed new Cold War as a central country, allied on both sides.

After the pandemic, BRICS nations contributed more to global GDP in terms of purchasing power parity (PPP, including exchange rates) than the sum of G7, which includes America, Britain, Germany, France, Japan, Canada, and Italy. The decline of G7 at the expense of BRICS countries began in 1992 (with Chinese growth), but with the pandemic, the curves have crossed and diverged. BRICS up, G7 down.

Does this mean we are at the peak of decoupling, that the world is splitting commercially into two regional blocs? Not exactly. In reality, globalisation is alive and kicking. This is because it’s a force towards which we are increasingly “oriented”, after the political damage caused by 19th-century European and American economic protectionism. It’s now all too fashionable to talk about the disasters of globalisation, especially because it has impoverished a portion of the middle-lower class in the US, that is, Trump’s voters, and in Europe, that is, the voters of the nationalist right. But what’s not said is that in 2022 trade between China and the US grew by 10 per cent compared to 2021. The production of iPhones is also shifting more and more from China to India, but it remains global. And with the new arms race in the Indo-Pacific, including new agreements signed by the Italian government at the G20 meeting in Delhi last month, the flow of trade between the global North and South will only continue to grow in both directions.

There is cause for tranquillity. Except for the nuclear threat. Not only because of the Ukrainian war or due to Putin’s missiles in Belarus and NATO’S new frontier in Finland, but also in Asia, where India deals with a more destabilised Pakistan, and China is engaged in naval games in Taiwan

There is, therefore, cause for tranquillity. Except for the nuclear threat. Not only because of the Ukrainian war or due to Putin’s missiles in Belarus and NATO’s new frontier in Finland, but also in Asia, where India deals with a more destabilised Pakistan, and China is engaged in naval games in Taiwan. And where a consolidation of dialogue between Iran and Saudi Arabia could create a pact towards the development of nuclear weapons in both countries.

To return to the initial question: How can we “orientate” ourselves in all of this? By understanding that there is no longer a confrontation between the old West and the new “Orient”. There is a global North that is redefining itself, which could drastically change in 2024 with the presidential elections (Will the war in Ukraine end if Trump wins?), where NATO seems to be strengthening with some signs from France of wanting a more independent role. The European Union (EU), having lost the UK, has internal forces flirting with Russia, and nations that could start again opening the doors to the Silk Road. There is a global South in search of cohesion, but whose future cannot be interpreted with the historical code used in the last centuries, as it will produce surprises, being the expression of mentalities quite different from those who transformed and dominated the world over the last five centuries.

/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Cover-OpenMinds2025.jpg)

More Columns

Puri Marks Sixth Major Stampede of The Year Open

Under the sunlit skies, in the city of Copernicus Sabin Iqbal

EC uploads Bihar’s 2003 electoral roll to ease document submission Open