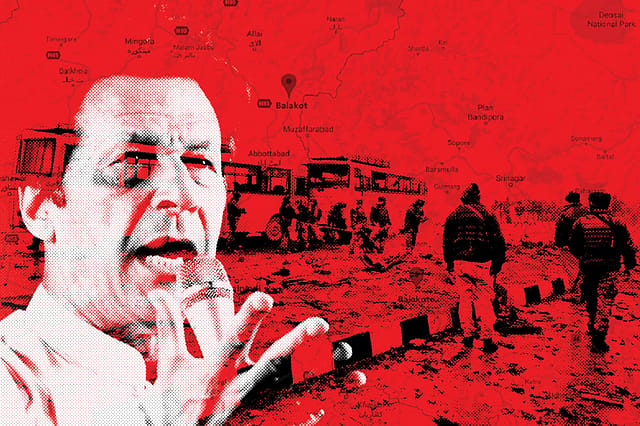

Hard Lessons from Pulwama to Balakot and Beyond

ON FEBRUARY 14TH, 2019, a suicide attacker associated with Jaish-e-Mohammad (JeM) drove an explosives- laden vehicle into a bus transiting Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) jawans in a convoy in Pulwama, Jammu and Kashmir. At least 40 jawans perished in that attack. It was the first time that JeM had used suicide attacks since the December 2001 attack on the Indian Parliament in New Delhi, which brought India and Pakistan to the brink of war. Given that JeM—like the Lashkar-e-Tayyaba (LeT)—is a well-behaved and obedient proxy of the deep state, there can be little doubt that Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) Directorate played a direct role in the attack. While the exact details of India's response remain disputed, India claimed that in the early hours of February 26th, it dispatched 12 Mirage fighter aircraft across the Line of Control (LoC) and into the airspace of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa to attack a training facility associated with JeM in Balakot. Those jets returned unscathed. Indian media, citing figures leaked by the Government, claimed the base was destroyed and some 300 people killed. Virtually all of these details have been disputed by Indian and international media alike.

Pakistan, while risibly denying that it has any evidence of JeM culpability, claimed that its air forces rallied to drive the Indian planes out of its airspace, causing them to drop their ordnance prematurely and causing no damage. Incidentally, a recording of a preacher ostensibly tied to JeM conceded an attack (hamla) took place but asserted no casualties. Despite asserting that no damage occurred, Pakistan dispatched fighter aircraft—likely American-made F-16s—to target purportedly 'non-military targets', across the LoC. India sent out MiG 21 Bisons after which a dog fight ensued. After various claims and counter-claims, it now seems clear that Pakistan shot down a MiG 21 and captured its pilot, Wing Commander Abhinandan Varthaman, who was returned after considerable delay on March 1st. India, in turn, shot down a Pakistani jet which crashed on Pakistan's side of the LoC. The fate of that pilot is unclear: Indian sources claim he was lynched by Pakistanis who mistook him for an Indian pilot while Pakistani sources deny this claim without offering alternative explanations.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

While the return of Varthaman provided an off-ramp for the crisis to begin de-escalating, many questions remain. What motivated the Pakistani attack and what made Pakistan expect it could get away with murder this time? Similarly, what motivated Pakistan to escalate tensions by inducting air power? Now that the crisis may be receding, what lessons did Pakistan learn?

Pakistani goals at Pulwama

I have argued elsewhere that the attack at Pulwama had several distal and one likely proximal objective. At the most general level of abstraction, since Pakistan is obsessed with changing maps but has an army that cannot win the wars it starts and nuclear weapons it cannot use without courting its own destruction, Pakistan uses terrorist proxies under the security of its nuclear umbrella to demonstrate that it is able to challenge India. More specifically, Pakistan has been worried as both Al-Qaeda Indian Subcontinent (AQIS) and Islamic State (IS) have sought to hijack its project in Kashmir. Both AQIS and IS have mocked Indian Muslims within and without Kashmir for their pusillanimity and failure to resist the rising tide of Hindu nationalism, the revivified interest in rebuilding the Ram Mandir at Ayodhya and failure to insist upon rebuilding the Babri Masjid which was destroyed by Hindu fundamentalists in 1992. Both organisations have chastised Indian Muslims for their parochialism and lack of interest in larger problems of the Ummah (community). While both AQIS and IS have largely failed to draw large numbers of recruits in Kashmir, this attack was likely aimed to help reclaim the initiative in Kashmir. The selection of a local Kashmiri boy, Adil Ahmad Dar, for this operation seemed well-placed to refocus the attention of Kashmiris upon the ISI-led struggle. Equally notable, Dar recorded a pre-attack video in which he criticised northern Kashmiris for shirking from the fight.

In addition to these distal causes, there is one proximate cause that likely explains the timing of the attack: a desire to influence India's elections. While it may seem counter-intuitive (the Pakistani deep state prefers a Modi win) for the simple reason that Modi and his Hindutva supporters embody the very threats that Pakistanis have long imbibed. With Modi at the helm, the Pakistani army can continue arguing that its heavy- handed role in running the country and hogging its resources is necessary. Additionally, Pakistan is confronting some fairly serious domestic challenges and a strong enemy next door has traditionally helped the deep state justify violence when needed and to encourage elements fighting the state to put down its arms. Observers may recall that after the November 2008 attacks in Mumbai, the Pakistani Taliban leaders, Baitullah Mehsud and Maulvi Fazlullah, declared a ceasefire and Pakistani army officials called them both "Pakistani patriots".

The internal challenges that the army is wrestling with include opposition to the so-called China Pakistan Economic Corridor, a simmering Baloch insurgency and a rising tide of Pashtun mobilisation against the deep state under the umbrella of the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement (PTM). PTM activists have been non-violently campaigning against human rights abuses of the Pakistan Army, which have long focused upon Pashtuns. One of the slogans protestors raise particularly disquiets the deep state: 'Yeh jo deheshatgardi hai, is ke picche vardi hai (The men in uniform is behind this terrorism).' The slogan summarises Pashtun beliefs that the deep state has created the terrorist menace in Pakistan but Pashtuns have been made the scapegoat and are at the receiving end of the army's brutality so that it can show the US and others that it is seriously confronting terrorists at home, for which it had been handsomely compensated until the Trump administration ended such payments.

While the deep state can kill Baloch—who comprise about 5 per cent of Pakistan's population—with impunity and intimidate any critics of this policy with violence, it cannot so easily kill its way out of its problems with Pashtuns. For one thing, Pashtuns are about 15 per cent of the population—and form the largest minority in Pakistan—but they may account for as much as 40 per cent of the Pakistan Army. Moreover, Pashtuns along with Punjabis have formed the ruling condominium since the late 1950s when Muhajjirs, who migrated from northern India, began to decline politically. The deep state needs to manage its Pashtun problem and having a menacing leader at the helm in India helps. It should be noted that Modi has not imposed such crippling costs upon Pakistan for its use of terrorism as a tool of foreign policy that may exceed the benefits of Modi's continued tenure.

Grounds for impunity

Given that a far less audacious attack at Uri precipitated a cross-border raid by Indian forces in 2016, why would Pakistan think it would escape consequences after Pulwama? As is well- known, the US President Donald Trump has made it clear that he wants out of Afghanistan. Trump obsesses over fulfilling campaign promises no matter how foolish, ill-informed or dangerous they may be. He sees this as a key reason for why he has a solid 35 per cent of voters who support him no matter what other dubious things he does —whether cavorting with porn stars while his wife is nursing his child or monetising the White House. Trump has dispatched Zalmay Khalilzad to work out some means by which Trump can succeed. These negotiations between the US and the Taliban rely heavily on Pakistan to persuade their proxies to co-operate. Notably, they have excluded the Afghan government. Trump's calculus is crude. If he wins the 2020 election, it doesn't matter what happens in Afghanistan. If he loses in 2020, it still does not matter for him what happens in Afghanistan.

Given the centrality of Pakistan to Trump's scheme, Pakistan likely expected the US to caution India to stand down after Pulwama. It is also likely that Pakistan felt that its importance to Trump's exit strategy in Afghanistan would afford it cover to escalate to air strikes on India's side of the LoC. Evidence for these suspicions is offered by the remonstrations of the Pakistani Ambassador to Washington DC, Asad Khan, who complained that US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo's response to India's airstrike was "construed and understood as an endorsement of the Indian position, and that is what emboldened them even more".

What did Pakistan Learn?

With the return of Varthaman and the resulting winding down of the crisis, Pakistan has likely learnt a worrying set of lessons. First and foremost, Pakistan has once again absconded from any meaningful consequences of using terrorism at Pulwama or escalating the conflict. There is no meaningful discussion of the US declaring Pakistan to be a state sponsor of terror or any other kinds of punitive measures. Whether or not India succeeds in getting Masood Azhar, the leader of JeM, designated at the United Nations will be an important move but not one that will be a game changer. Second, coverage in papers of record such as the New York Times and the Washington Post repeated the tired false equivalence that equated India—the victim—with Pakistan—the perpetrator. Editorials and assessments of Western commentators applauded Pakistan's Prime Minister Imran Khan for his speech which they deemed 'conciliatory' despite the fact that it was anything but. Similarly, editorials calling for a 'resolution of Kashmir', all of which demonstrate an impoverished understanding of history, also rewarded Pakistan because they seemed to imply that Pakistan has defensible equities in Kashmir when, of course, it does not.

Finally, and the most worrisome of all, there is little appetite in India to know what the Government intended to do and what it succeeded in doing. Indian citizens who are asking these questions are being dismissed as anti-national while non- Indians asking these questions are being dismissed as Pakistan apologists or worse. While accepting whatever account is offered—irrespective of the various competing claims—may seem politically loyal, it is not actually helpful to India's overall ability to handle the beast on its border. Worse, while everyone expects Pakistan and its press to promulgate rank fictions, the international community does have higher expectations of India. Most importantly, the Pakistani deep state does know what happened. It can assess whether Pulwama was worth it in the end. And, as I've argued, it likely has concluded this already. But if India did not live up to the maximalist claims about the assault on Balakot, when there is another attack, Indians will demand an ever-more robust response which India may not be able to deliver. This dynamic may force India's hands in ways that are not only counter-productive but may catalyse a conflict that India cannot control. This is something that genuine patriots should be very worried about.

Also Read