Absolute Xi

Having dismantled the system of collective leadership, the Chinese president will now need more than loudspeaker nationalism

Pallavi Aiyar

Pallavi Aiyar

Pallavi Aiyar

Pallavi Aiyar

|

21 Oct, 2022

|

21 Oct, 2022

/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/China1.jpg)

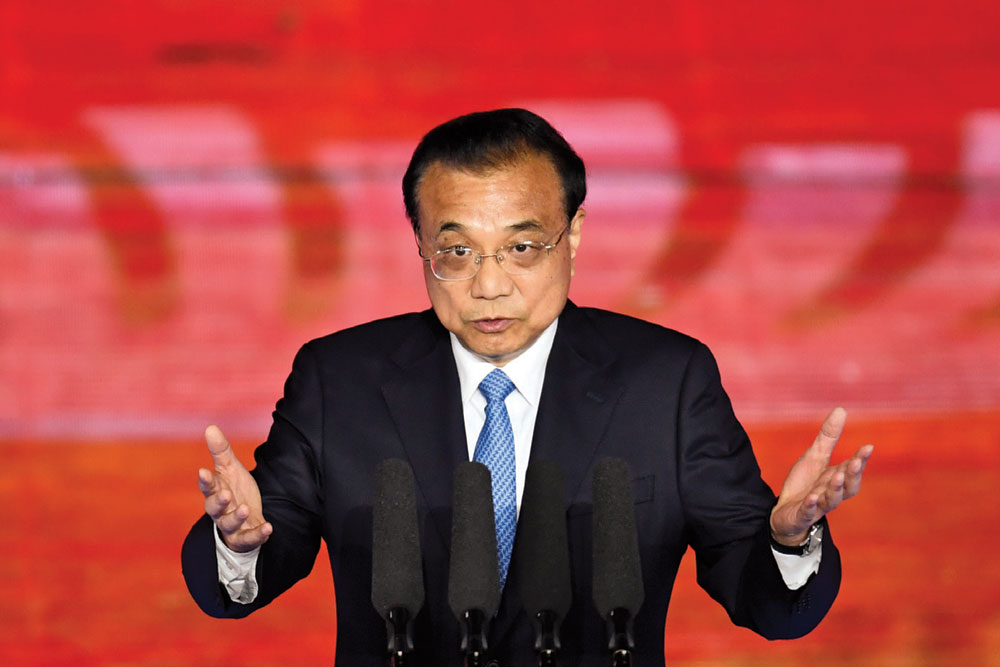

Chinese President Xi Jinping addresses the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China in Beijing, October 16, 2022 (Photo: Getty Images)

XI JINPING’S CONFIRMATION as the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) general secretary for a third term, at the 20th Party Congress, will complete the dismantling of the post-Mao system of collective leadership that took decades of careful construction.

During the seven years I lived in China, between 2002 and 2009, the country was presided over by the president-prime minister duo of Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao. The two ruled in consultation with other members of CCP’s Politburo Standing Committee, a body reminiscent of a corporate conglomerate’s board of directors. It featured a clutch of mostly bespectacled, suit and tie-clad men (no woman has ever made it to the group), with a technocratic bent.

It was during this era that China honed the pragmatic economic reforms and diplomacy that saw it integrate into, and eventually dominate, the global trading system. The elevation to power of Hu-Wen in 2003, and their clockwork-like departure a decade later, was indicative of what many assumed had replaced the devastating chaos of the Maoist decades: regular, peaceful transitions of power from one group of leaders to another.

Xi Jinping has spent the last 10 years upending all of this: the pragmatic economics, the diplomacy-focused foreign policy, and the predictability of the governing system, injecting more than a dollop of Mao-reminiscent madness into a China where such excesses were thought to belong to the past. His heavy-handed, almost absurdist, zero-Covid policies have ordinary Chinese people behaving more irrationally than at any point since the Cultural Revolution. They have been reduced to taking Covid tests as habitually as brushing their teeth and being imprisoned for weeks at the whiff of someone else’s asymptomatic, post vaccination-infection.

Where Xi’s predecessor Hu had displayed less personality than an automaton, Xi has cultivated a cult of personality that rivals that of his North Korean counterpart. His portraits are hung everywhere—in government offices, schools, religious sites, and homes. In one verbose, 2017 Xinhua article, the writer—clearly an accomplished sycophant—feted Xi with a bouquet of florid titles, including: “groundbreaking leader,” “diligent worker for the people’s happiness,” and “chief architect of modernization in the new era.”

Xi has concentrated power in his person by ruthless sidelining of rivals and the assertion of party control across the full range of governmental and administrative areas. One obvious effect has been to hobble the head of China’s government, Prime Minister Li Keqiang, converting what was a position of co-pilot into an ineffectual sidekick.

Xi’s latest extension of term as party leader comes four years after his most brazen move, discarding the country’s presidential term limits. In a manifestation of George Orwell’s dictum, “All animals are equal, but some more equal than others,” this limitlessness apparently only applies to Xi himself. The less exalted, like Premier Li Keqiang, will almost certainly step down as premier in March next year, in accordance with the convention of a two-term limit. At the ongoing Congress, two members of the politburo’s standing committee, Li Zhanshu and Han Zheng, who are 72 and 68 respectively, are expected to step down, having reached retirement age.

Only Xi is set to indefinitely fuel forward on his toxic brand of nationalism and censorship.

When I last visited China in 2019, the most palpable change since the time I’d lived there was the firewalled internet. This precluded the use of any social media, news websites or services app that I actually used: WhatsApp, Google, Twitter, Uber, the New York Times. It was as if the internet, the single-most defining feature of global contemporary life, did not exist in China—or more accurately, existed wholly in a parallel universe.

I had to remind myself that I’d got my first Gmail account when I was resident in Beijing. Ditto for Facebook, which I joined in 2006. There were certainly occasional China-related articles that would fail to download from a foreign news website, but on the whole, I had been able to research any topic freely, using Google.

How has Xi Jinping been able to recast China away from the cautiously liberalising, globalising trajectory that it was on in the first decade of the new millennium? To begin with, he effectively used a wide-ranging anti-corruption campaign to simultaneously eliminate rivals and gain popularity with a citizenry that was weary of the operatic levels of corruption rife in government and party. According to official data, CCP investigated 393 senior cadres, as well as 631,000 lower-level functionaries, between December 2012 and June 2021. These purges conveniently weeded out powerful politburo members like Zhou Yongkang, former head of China’s security and law enforcement institutions, whom many had seen as a competitor to Xi.

In a manifestation of George Orwell’s dictum, ‘all animals are equal, but some more equal than others,’ this limitlessness only applies to Xi himself. Only Xi is set to indefinitely fuel forward on his toxic brand of nationalism and censorship

Over the years, he has also brought the country’s increasingly powerful private sector to heel. This has ensured that CCP remains rival-free while also tapping into populist sentiment against growing income inequality and the excesses of crony capitalism. Some of China’s most dynamic technology companies, like Tencent and Alibaba, have been cut down to a size acceptable to Xi, via a combination of new regulations, investigations, and fines.

From 2019 to 2021, state-owned enterprises, whose share of the economy had been steadily declining in the pre-Xi era, acquired more than 110 publicly traded Chinese companies. These were valued at over $83 billion, according to accounting firm and consultancy PwC.

But it is Xi’s successful fanning of nationalist pride that has done the most to shore up the president’s popularity, replacing economic growth as the primary source of CCP’s legitimacy. Assisted by a ‘West’ in both economic and moral decline, following first the financial crisis of 2008, and later the Trump years, China under Xi, has asserted itself as a global power that will not be manipulated in the interest of others.

Xi, who is also chairman of the Central Military Commission, has beefed up China’s military firepower, building the world’s largest navy, and developing cutting-edge ballistic missiles. The power to act autonomously on the international stage, regardless of censure, is like Viagra to a nation that has long felt unfairly neutered by foreign powers.

Something people tend to get wrong about China is that ‘authoritarian’ does not necessarily equate ‘illegitimate’. Through the years I lived in Beijing, and indeed, even now, ordinary Chinese people—in particular those who have risen to the ranks of the country’s burgeoning middle class—are enthused by the upward trajectory of their lives. Further, they often directly attribute improvements in their material circumstances to the policies of their authoritarian government.

THE CHALLENGE GOING forward for Xi will be to retain legitimacy in the context of a slowing economy, the disaffections engendered by the zero-Covid policy, and an increasing anti-China bent of mind amongst its neighbours and main trading partners. The latest development in the US-China trade war was the announcement on October 7 by the Biden administration of wide-ranging export controls. These would shut out firms in China from many advanced technologies of US origin, including chips used for Artificial Intelligence (AI), software to design advanced chips, and the machine-tools to manufacture them.

Even the European Union (EU), which has been less aggressive than the US in its dealings with Beijing, froze an investment deal with Beijing in May 2021. The move followed concerns over human rights violations in the Xinjiang region, where Uyghur minorities have been victims of systematic abuse.

Further, China’s property market, a source of jobs and household wealth, is melting down. Youth unemployment is at a record 20 per cent. Foreign investment has faltered. And the widespread lockdowns and mass quarantines of zero-Covid have hurt consumer demand and stalled businesses.

For younger Chinese, under the age of 40, this state of affairs is shocking. This is a demographic that has become habituated to expecting a steady rise in economic prospects. “Eating bitterness”—a Chinese phrase that indicates stoic belt-tightening—may have been par for the course for their parents, but for young people it is an anachronism, untinged by retro-nostalgia.

Xi has concentrated power by ruthless sidelining of rivals. One obvious effect has been to hobble the head of China’s government, Prime Minister Li Keqiang, converting a position of co-pilot into an ineffectual sidekick

My years reporting in China had included several pieces the gist of which was Beijing’s seemingly successful soft-power drive to win friends and influence people amongst its neighbours, many of whom were former foes. China’s foreign policy at the time emphasised its “peaceful rise”, a term popularised by the Hu-Wen duo. It was a far cry from the coercive, “wolf warrior diplomacy” of the present day.

In a 2005 survey by the Pew Research Center, China was found to have a better public image than the US in almost every one of the 16 countries studied, from Britain, France and Poland to Turkey and Indonesia. A similar result would be difficult to imagine today, given that Beijing is involved in acrimonious disputes from the South China Sea to the Indian border and the Sea of Japan. Xi’s aggressive foreign policy stance has pushed nations that have little in common, save a wariness about Beijing’s intentions, into an ABC (anybody but China) strategic club.

I have written in the past about how predictions of China’s collapse have fundamentally underestimated CCP’s skills at walking the tightrope of contradictions—in particular between economic liberalisation and political authoritarianism. But under Xi, the space for dissent has shrunk, amping up the authoritarianism, while the growth has slowed, so that China’s existential contradictions are increasingly hard to reconcile or manage.

If Xi turns to aggressive nationalism, possibly by attacking Taiwan, it may put some of the domestic turmoil on hold for a while. But it would pose serious external dangers to Beijing. In his opening speech at the party congress, Xi reiterated that his plans for Taiwan remain core to his strategy for national “rejuvenation”. He added that while his preference was for “peaceful reunification”, China would “never promise to renounce the use of force”, if it came to that.

Where Hu Jintao had displayed less personality than an automaton, Xi has cultivated a cult of personality that rivals that of his North Korean counterpart

The problem for Xi is that by whipping up frenzy over Taiwan at home and presenting reunification as central to China’s recovery from a “century of humiliation” at the hands of colonial powers, he has limited his room for manoeuvre. An actual military confrontation with Taiwan would pull in the US and other major regional powers, exhausting Beijing’s economic and diplomatic reserves. And quite possibly presenting Xi with a circle that he cannot square.

Xi Jinping may have just established himself as the possible forever-supremo of the People’s Republic of China, but he’s going to need more than just loudspeaker nationalism to navigate the country to the prosperous, stable and efficient future its citizens want and have been promised.

/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Cover-Iran.jpg)

More Columns

Tesla Robotaxis Hit the Road Open

A childhood memory of Emergency in our ancestral home in Kannur Ullekh NP

Trump claims credit for ceasefire, blames Israel, Iran for violations Open