A Lethal Impasse in Gaza

What is the way out as the international pressure on Israel mounts and the humanitarian crisis deepens?

Jason Burke

Jason Burke

Jason Burke

Jason Burke

|

15 Mar, 2024

|

15 Mar, 2024

/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Gaza1.jpg)

Evening prayers at the Haram Al-Sharif in Jerusalem’s Old City, March 10, 2024 (Photo: Reuters)

IN THE MORNING the yellow limestone walls of Jerusalem’s Old City glow in the spring sunshine and the gold of the Dome of the Rock shines. There is little sign of tension. The tourist buses are parked below the Garden of Gethsemane, the monks walk on Mount Zion, the Orthodox Jews cluster at the bus stop outside the Western Wall, and Muslim schoolchildren rush through the market opposite the Damascus Gate, late for classes but with enough time to buy a handful of sweets. In the Muslim cemetery on the eastern flanks of the city, below the long wall of the Haram al-Sharif, a painter carefully inks the carved inscription on a gravestone.

Later, the city police and the border police will deploy in their hundreds. Most are very young conscripts, armed with batons and assault rifles. Since Ramadan began earlier this week, there have been scuffles with young Muslim men. It is likely that there will be more. This is not an easy time, for the worshippers, the 30,000 inhabitants of the Old City, the shopkeepers and restaurateurs, or, indeed, for the teenage police officers who push them around. Everyone is fearful, and with good reason.

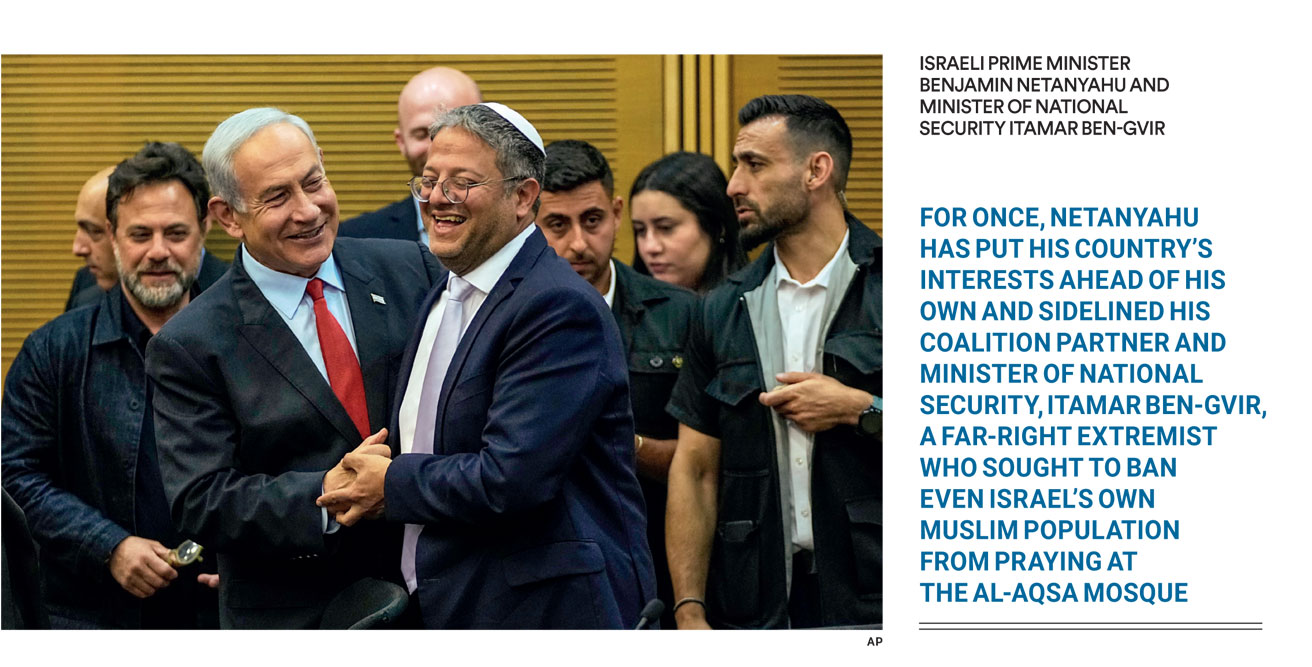

Authorities have done their best to ensure calm. For once, Benjamin Netanyahu, Israel’s prime minister, has put his country’s interests ahead of his own and sidelined his coalition partner and minister of national security, Itamar Ben-Gvir, a far-right extremist who sought to ban even Israel’s own Muslim population from praying at the al-Aqsa mosque, the third most important site in Islam, during Ramadan. For the next weeks, responsibility for security around the Haram al-Sharif, the raised plaza that is known as the Temple Mount to observant Jews, has been stripped from Ben Gvir’s ministry and given to local authorities, who have every reason to want to keep the peace. This is not the case with Ben Gvir, whose habitual rabble-rousing rhetoric has been the main driver of his career and a key contributing factor to the current crisis.

Quite exactly who is to be allowed into the Haram al-Sharif to pray is not entirely clear. Theoretically, women and children have permission, but not men under 60. This is necessary to ensure security, Israeli authorities say. In recent years, the Haram al-Sharif has been the site of protests, police raids and much else that have led to, in one case, a war. Everyone knows that a similar breakdown of order now, after five months of war and tens of thousands of dead in Gaza, with the entire Middle East region on the brink of a major conflagration and billions of Muslims watching closely, would be disastrous. Everyone except Ben Gvir of course, and Hamas, who are basing much of their current strategy on such an outcome.

Exactly who is to be allowed into the Haram Al-Sharif to pray is not entirely clear. Theoretically, women and children have permission, but not men under 60. This is necessary to ensure security, Israeli authorities say. In recent years, the Haram Al-Sharif has been the site of protests, police raids and much else that have led to, in one case, a war. A similar breakdown of order now would be disastrous

In reality, the Israeli authorities are being pragmatic. They need to control numbers, but also avoid confrontation. There are 2.9 million Palestinians in the West Bank, effectively banned from entering Israel since the beginning of the war. Discreet conversations with religious and community leaders have been underway for weeks. The elderly, families, the sick can come to pray, the message has been. Just keep the young men away. So far, the call of Hamas for a mass march on Jerusalem, or Al-Quds as it is known in the Islamic world, to liberate the holy sites from Israeli, and so Jewish, control has yet to materialise. So this is a rare bit of good news, as is the calm on the sunny spring mornings.

CALM IS A RARE COMMODITY in the Middle East at any time, and particularly now.

For months, there have been dire predictions of a regional conflagration in the Middle East as a result of the conflict in Gaza. These fears were first raised in the immediate aftermath of the surprise attack launched by Hamas into Southern Israel in October last year which killed 1,200 people, mainly civilians in their homes or at a music festival, and led to another 250 being taken hostage.

Since, there has been much violence. At its centre has been Israel’s relentless, grinding offensive in Gaza itself. Elsewhere, the Houthis have fired missiles at shipping in the Red Sea, supposedly out of solidarity with Palestinians but also for domestic political gain. The once-rebel Yemeni movement has had its military sites bombarded by the US and the UK as a result. In Iraq and Syria, a motley crew of Islamist militia have attacked US interests, on one occasion with deadly consequences.

Along Israel’s northern disputed frontier, the long-running attritional war has been fought through the autumn, the winter and now into the spring. Early this week, Hezbollah, the Islamist military and political movement based in southern Lebanon, fired 70 rockets into Israel in a 24-hour period. Israel retaliated with an airstrike far up in the Beqaa Valley and artillery fire. Then of course there is the West Bank, occupied by Israel in 1967, and as restive now as it has been for decades. This, Israeli strategists say, is the third front after Gaza and the north. Palestinians speak of a “storm gathering” that will break across the hills west of the Jordan soon.

Into this toxic mix you can throw a multitude of bad actors: extremist settlers and their supporters in Israel, Muslim militants hoping the conflict will mobilise the masses behind their defeated campaigns in the Middle East, political leaders of all stripes across the region who see benefit in continual conflict, countries in the Global South seeking to maximise their own interests, Western powers caught in the web of their own diplomatic casuistry, an army of online trolls pushing anti-Semitism and Islamophobia and conspiracy theories, and a global crowd of observers who are as outspoken as they are ignorant. For the first time in several thousand years perhaps, it is not Jerusalem that is the global centre of false prophecy.

All the actors in this conflict believe that they have the initiative and can control events. This is particularly true of the three most important involved: Israel, Hamas, and the US. All believe in their eventual victory; or success at least. In reality, all are facing very serious constraints that mean there is no conceivable way they can achieve their immediate goals. All are interpreting events and others’ actions from their own perspective, and so making fundamental strategic errors.

TWENTY TWO YEARS ago, at a US army base on a plain in Afghanistan outside Kabul, I attended open air briefings by US soldiers on their war against al-Qaeda and Afghanistan there. Every morning a colonel would say that 170 or 180 or 190 days had elapsed since the 9/11 attacks, and then give a short biography of one of its victims.

In their afternoon briefings, now online of course, Israeli officials have begun to do something similar. The number of days since the October attacks is carefully noted and, of late, a short biography of one of the soldiers killed in Gaza read out. These now number 249. Israel’s Jewish population is seven million, so this would be the rough equivalent, for India, of 50,000 casualties. This number is expected to rise.

Israel remains a deeply traumatised society. Everyone knows someone who was killed or injured last October. Israelis point out that many were killed that day in their safe rooms— the room in every Israeli house meant to be a semi-secure sanctuary in case of attack. To them, the threat that faces them is existential. This may not be true, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t perceived as so and explains in part why public opinion is so determinedly supportive of the war in Gaza.

There is enormous anger and disappointment directed at Prime Minister Netanyahu, the entire political elite and the security establishment. All failed to foresee October’s attack, then failed to mobilise fast enough to defend Israeli citizens, and have made questionable decisions since. But only a vanishingly small number of Israelis actually want the war to stop before achieving the goal of “crushing Hamas”.

The economy is suffering, the opprobrium of much of the rest of the world is uncomfortable, and the casualties are painful, but this is what is seen as necessary. Paradoxically, though confidence in the military has been shattered, there is still sufficient belief in its capabilities for almost everyone to be certain that Israel’s soldiers will bring victory.

But there are several major problems facing Netanyahu and Israel more generally. One is that to defeat Hamas ‘totally’ is virtually impossible. It is a multifaceted organisation with a military wing, an administrative structure, a political leadership scattered across Middle Eastern capitals, a presence in the West Bank, and an ideology. Only the first two are in Gaza and neither can be eradicated entirely. Israeli officials speak of the defeat of Japanese or German fascism in World War II as a definitive victory over an idea but the comparison is specious, however reassuring.

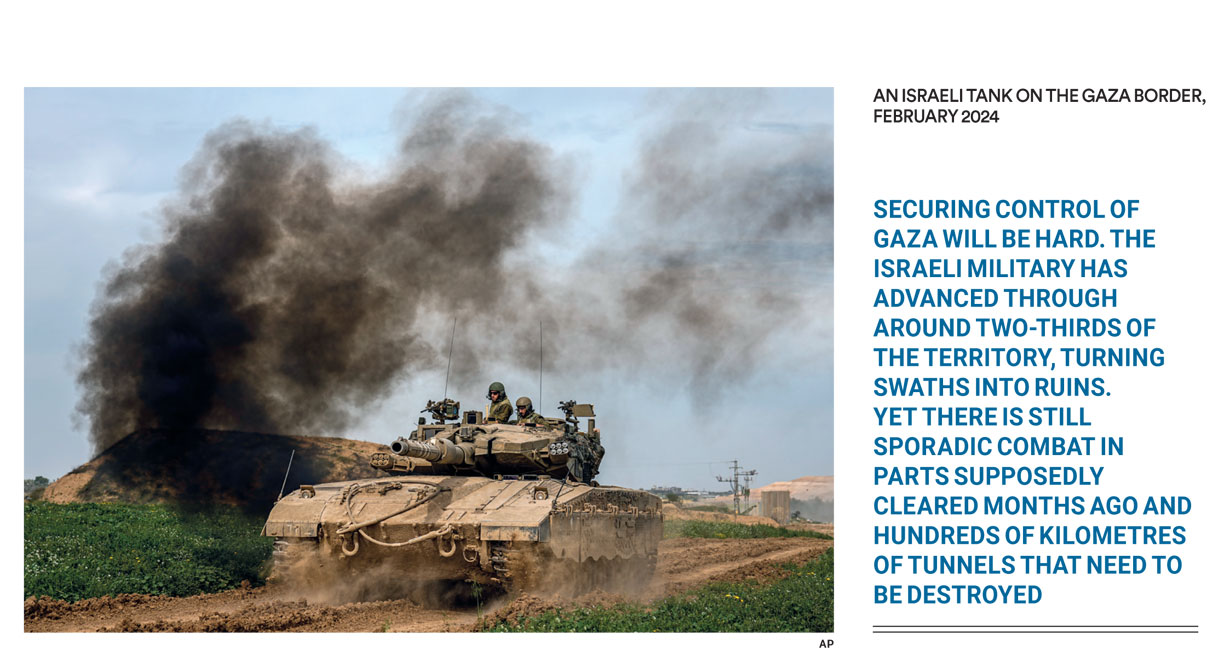

The second is that even securing total control of Gaza will be hard. The Israeli military has advanced through around two-thirds of the territory, turning swaths into uninhabitable ruins. Yet there is still sporadic combat in parts which were supposedly cleared months ago and hundreds of kilometres of tunnels that need to be destroyed. An airstrike at the weekend that may have killed a senior Hamas leader—the first top official in Gaza to have been potentially harmed—hit a tunnel in the centre of the territory in an area that the Israelis have been fighting in and around for weeks.

To complete their campaign, the Israeli military needs to take control of Rafah, the southernmost city by the border with Egypt where Israeli officials say the remaining fighting force of Hamas is based. Seize the town and a strip of land along the border and then total territorial control—at least on a map—can be declared. Except, there are a million displaced Gazans living in Rafah, so they would have to be moved before a new campaign there, and the Israeli military would need a new mobilisation of possibly tens of thousands of reservists for the effort. Perhaps trickiest of all, US President Joe Biden has declared an offensive in Rafah a “redline” that Israel should not cross if it wants to retain what has so far been Washington’s unquestioning support despite growing global outcry at civilian casualties and the acute humanitarian crisis now unfurling in Gaza. Can Israel fight without the US? Almost all the hi-tech weaponry necessary to take out bunkers where the Hamas leadership is almost certainly hiding comes from the US. So, though the Israelis have stocks of or can source more basic weapons, they would lose a key part of their arsenal. A close relationship with the US has been the bedrock of Israel’s security doctrine for 50 or more years. Risk this and you risk everything, Israeli analysts say.

Finally, there are the hostages held by Hamas, of whom perhaps 100 are still alive. For them time is running out. More fighting could be fatal and an attack on Rafah especially so. This, and other issues, could split Netanyahu’s coalition, plunging Israel into political uncertainty at exactly the wrong moment.

So, does Israel—or at least Netanyahu—have options? Yes. Is the country in charge of events? Hardly.

But then Hamas is hardly running the show either. At the weekend, Ismail Haniyeh, the organisation’s most senior political leader, listed what it wanted in return for any ceasefire: these included a major release of Palestinian prisoners from Israeli jails, more humanitarian aid for Gaza, a complete withdrawal of Israeli forces from the territory, and a definitive end to the conflict. Indirect intermittent negotiations have been going on since the end of December. There was optimism a week ago of a pre- Ramadan breakthrough, but none came. One reason is that both sides believe they will be in a better position in a few weeks. The Israelis think they will degrade Hamas further. Hamas thinks that a combination of international outrage and a mini-uprising in East Jerusalem or the West Bank will weaken Israel.

But then Hamas is not in a great position either. It has lost almost all the military capabilities built up during the 15 years it ran Gaza. Several thousand of its best fighters and many mid-ranking commanders are dead. However the war ends, there will be no piece of territory anywhere that it controls. The vast money-making machine that Gaza provided has ground to a halt. A bid to patch up relations with other Palestinian factions in Moscow last month was largely unsuccessful, meaning Hamas will stay officially marginalised for the moment. The atrocities of October 7, such as widespread and documented sexual violence, have hardly improved its public image in the West or in Arab capitals. Hamas is down, and though it may not be out, does not control its own destiny either.

Finally, there is the US. Biden’s “redline” comments signalled the definitive end of his patience with Netanyahu and final acceptance that the “bear hug” strategy adopted immediately after October 7 was a failure. The fierce imperatives of the looming election in the US and the need to rally a progressive vote horrified by the president’s continued failure to rein in Israel have led to a major rethink by Democratic Party strategists. But can the US actually knock heads together in Israel or anywhere else to bring an end to the violence and set the region on a path to some kind of stability?

The deepening humanitarian crisis is the best current example of the superpower’s impotence.

Though the images of the vast flotilla that will build a temporary port off Gaza to facilitate aid deliveries and so alleviate suffering in the territory are impressive, the fact that the US is obliged to make such a spectacular gesture is not. The port will not be operative for weeks, possibly months, and even when it is functioning there is no plan for how aid can be distributed in Gaza, currently plunged in Hobbesian anarchy. It is there because Netanyahu has consistently refused US requests to allow more aid into Gaza and develop coherent plans for administering its 2.3 million population. The US would like this to be done by a “revitalised” and reformed Palestinian Authority, which currently partially runs the West Bank when the Israelis are not running roughshod over it. Netanyahu has refused this plan but not proposed anything of his own. Until this conundrum is resolved, the much more ambitious ideas of recognition of Israel by Saudi Arabia and other powers, and its integration into a new region-wide economic and security architecture remain pipe dreams. If anyone in Washington thinks they can impose their will on the most fractious region in the world, they are as deluded as any actors on the ground. And in the meantime, the various dials—civilian casualties in Gaza, the deaths of hostages held by Hamas, the world’s outrage—tick further into the red.

THIS LETHAL IMPASSE is unlikely to last forever. Events move fast in the Middle East. Something is likely to give and this equilibrium of inability will collapse. Individual politicians in Israel could move to undermine Netanyahu’s position, potentially removing the biggest block of all to forward movement. Equally, an Israeli airstrike, using one of those hi-tech weapons supplied by the US, might kill Yahya Sinwar, the Hamas leader in Gaza and mastermind of the October 7 attack. This would simultaneously collapse resistance in the territory and give Netanyahu the excuse to declare a triumphant victory. A clash on the Haram al-Sharif as police seek to limit the number of worshippers could turn bloody, and anger could surge out across the region from Jerusalem.

For the moment though, the Old City is calm. The sun is going down, painting the walls a warmer yellow than in the morning, and the dome of the al-Aqsa mosque has caught the last rays. The only sound of war is two cannons, but they are firing only to announce the end of the day’s fast.

/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Cover_Kumbh.jpg)

More Columns

What does the launch of a new political party with radical background mean for Punjab? Rahul Pandita

5 Proven Tips To Manage Pre-Diabetes Naturally Dr. Kriti Soni

Keeping Bangladesh at Bay Siddharth Singh