The Original Existential Hero

Over the last four decades, the achingly beautiful story of Rama, prince of Ayodhya—his exile, his abducted wife, his glorious victory over the rakshasa king made possible with the help of his magnificent monkey companions and his triumphal homecoming—has been placed at the centre of a religious nationalism predicated on hierarchies and exclusions. Now, more than ever, as this robust, diverse and generous tradition that feeds our art forms and our stories is narrowed to a single telling and a single ideology, it is appropriate to remind ourselves just how rich and widespread Rama's story is. In doing so, we might well consider why it is that Rama himself continues to haunt our cultural discourses, centuries after his story was first told on the northern river plains of the Indian subcontinent.

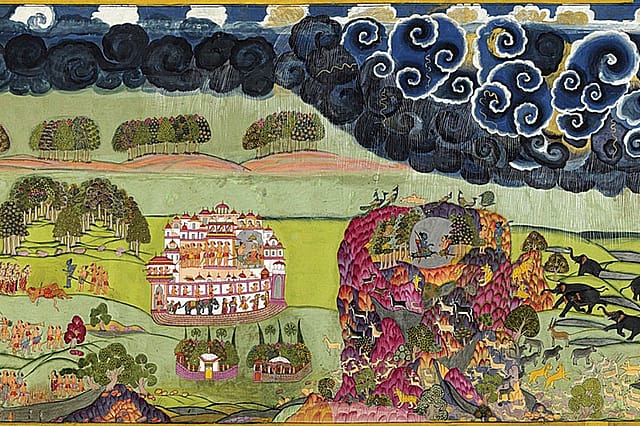

We are not clear about the origins of the story we now call the Ramayana. What we do know is that between the 5th century BCE and the 3rd century CE, a beautiful Sanskrit text developed around this story and was attributed to a poet-sage named Valmiki. Something about this story excited the imaginations of individuals and communities so much that hundreds of Rama stories proliferated across South Asia and beyond. They are told in text and in song, in dance, music, painting and sculpture, each unique in itself but still conforming to a fundamental structure of characters and events such that these stories together now constitute a tradition.

Modi Rearms the Party: 2029 On His Mind

23 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 55

Trump controls the future | An unequal fight against pollution

What is it, then, about this story that refuses to be contained, either by the time in which it was written or by the space that it purports to occupy? Why are there so many Rama stories? Why do they take positions of opposition and subversion as much as they act as mirrors that both complement and supplement the many-layered and multi-faceted narrative that responds so pliably to the needs of the teller, be the teller Kamban (Ramavataram, 12th century CE) or Tulsidas (Ramcharitmanas, 16th century CE), Mani Ratnam (Raavan, 2010) or Samhita Arni (The Missing Queen, 2013)? Why does each historical and political moment feel the need to appropriate the Ramayana to its needs? How is it that artists of all kinds find emotions in the story that can be explored and newly expressed? Devotees of Rama might not find the need to ask or answer these questions but for the rest of us, who situate ourselves differently in relation to Rama, the questions we ask (if not the answers we find) will surely tell us something about ourselves and our own quest for meaning, both aesthetic as well as existential.

Thirty years ago, AK Ramanujan reminded us that by acknowledging the multiplicity of Rama stories, we are able to comprehend more fully the majesty of the Ramayana itself. He argues that these many Rama stories are not 'versions' of a fixed 'original' story. Rather, they are fullblown and deeply felt reconfigurations of a story that is already known. The story is told again because it arises from a question that the prevalent (or dominant) story does not answer. It is retold because we believe that the story can answer the questions that we are asking, that it can include us within its rich tapestry of love and longing, of trust and betrayal, of difficult choices and shattered dreams. The focus of our anxieties and our aspirations is Rama, the central character of the story, from whom the most is demanded both within and without the story, perhaps as a result of his being both human and divine.

Ever since the theology of Vaishnavism indelibly coloured the story of the 'perfect man', devotees and believers have kept Rama in their minds as part of their faith and religious practice. A story of god's presence among humans and his infinite grace provides a reassurance and certainty that is unmatched by anything profane. For this reason alone, the divine presence and all it promises should be recalled fully and frequently by the devotee. But those of us who approach Rama's story without religious belief will have other reasons, perhaps equally passionate, for our attachment to it. I believe we remain committed to retelling Rama's story over and over again because we have not been able to come to terms with the troubled love and the heartwrenching loss in the lives of Rama and Sita. The story haunts us because it is tragic, ending in a separation between a husband and a wife who have loved each other through much trial and tribulation. Some of us have sympathy for both Rama and Sita, some of us find it difficult to understand what motivates the characters in the story to behave in the ways that they do, be it Dasharatha, Kaikeyi, Ravana or Rama. Whatever our question, we return to the story, rather than to history or sociology, to find the answer.

Over the same centuries that wove righteousness and divinity into the story of the god who lives as a man among humans, women have been made uncomfortable by Rama's actions towards Sita after he brings her back from Lanka. For a man such as him, or even for a god such as him, to be so disturbed by marketplace gossip about his wife's chastity that he banishes her, pregnant and alone, into the forest simply does not make sense. Lest we believe that it is only the feminisms of modernity that have opened up this critique of Rama, women's songs in the eastern dialects of Hindi such as Maithili and in Telugu and Marathi (to name just a few examples) from hundreds of years ago will assure us that even our ancestral mothers and sisters were troubled by Rama's behaviour and found words with which to reprimand him, to caution Sita and to sympathise with her predicament. It is worth pointing out that these songs and ditties are usually the purview of non-Brahmin women but in more places than we care to notice, mothers, wives, sisters have found in the silence of the Ramayana's women a place that they can fill with their own voices. I would argue that it is this discomfort with a figure so lauded and honoured by traditional social and religious groupings that keeps Rama alive in the minds and hearts of women. As long as patriarchies perpetuate a rigid and uninflected idea of Rama as the paradigmatic Indian male, women will be compelled to respond with resistance and subversion, even if those forms of expression continue to lie outside the so-called canon of the text.

My personal attachment to the Valmiki Ramayana also revolves around the love story between Rama and Sita and my continual attempts to understand how Rama could have treated the woman he loved more than anybody the way he did. Valmiki's text implicitly suggests various reasons for Rama's unexpected behaviour, reasons and motivations that are rooted in his own inner conflicts which are all too human. It is clear that Rama is mad with grief when Sita is abducted. He mourns for her as one would for a beloved that has died. I believe this is crucial to understanding how he treats Sita once he has her back. For a constellation of reasons that involve dharma, his impending kingship and the destroyed reputation of his own father who succumbed to his love for a woman, Rama decides that once Sita has been taken away by Ravana, he will never really be able to have her back. She will always be stained by her separation from him and her confinement in the house of another man, however involuntary those might have been. Although he is utterly heartbroken at what he knows will eventually be a continued (perhaps permanent) separation, Rama does everything needed to rescue his wife. He claims that the repeated tests of her chastity are not for him, they are for the world to know that she has remained both faithful and safe from sexual aggression. I may not agree with Rama's reasons for doing what he does, but at least I know that he has them and that they might arise not from a lack of circumspection but from an excess of it. This quality of considering the choices before him, aware that they might not lead to ease or comfort, brings me to Rama. It does not push me further away from him.

Surely, this is the very nub of our continued engagement with Rama and his story: how do we reconcile ourselves to the fact that 'good' people do 'bad' things? Vaishnava theology, which elevates Rama to being an avatara of Vishnu, relieves its followers from having to contend with 'good' and 'bad.' Such questions haunt those of us who come to the story without surrender to Rama's divine nature and status. What binds us, this latter group of non-believers, to Rama is his essential humanity: his grief, his desire to always do the right thing and finding that sometimes, actions based in his best intentions have had the worst consequences for those that he loves. Rama's existential conflicts are the same as ours—he must negotiate the compulsions of his personal desires against the expectations that others have of him.

We stay with Rama-the-human because of his resemblance to us. We see our own lives reflected in his: we recognise the oppositional pulls of family and society, we experience the tensions between love and duty, we struggle with the often unbridgeable chasm between personal happiness and a larger good.

A single politically and socially dominant Ramayana story shows us one way of resolving these conflicts, a way that is idealised by patriarchal hegemonies into the only way for us to be 'good' in the world. When those of us who seek to challenge these and other hegemonic structures in our retellings of the Ramayana, we are talking back to power in a language that we have made our own. Power cannot pretend that it does not understand our words, for it is their language we are using, it is their language that we have taken away from them. The Rama story haunts us because we know it can be ours, too.