Lockdown Lessons from Gandhi

Finding your inner hermit

/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Innerhermit1.jpg)

(Illustration: Saurabh Singh)

On September 22nd, 1921, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, ideologue and Mahatma of the greatest mass uprising in the annals of the farflung British Empire, was, by his own admission, apprehensive to the point of fear. His anxiety was embedded in a question: would he look like a lunatic if he appeared before the people in nothing more than a loincloth?

It has been widely recognised that Gandhi’s greatest contribution was not the freedom of India from the British, but the liberation of Indians from fear. Without the second the first would have been impossible. The Indian mindset of 1920 is aptly illustrated by an anecdote from that time.

When Gandhi launched his non-cooperation movement, Satyendra Prasanna Sinha—1st Baron Sinha, KCSI, PC, KC, first Governor of Bihar and Orissa, first Indian to become member of the Viceroy’s Council and member of the British ministry—is believed to have remarked: ‘What does this man in a dhoti think he is doing? The British Empire will last 400 years.’ Photographs of the Indian Baron do not show him in the traditional dhoti. He wore a splendid tie between stiff collars and a perfectly ridged handkerchief in the breastpocket of his superbly tailored suit. Once the dhoti-clad Gandhi released Indians from fear, the Raj could not last another 30 years.

But in 1920 the Mahatma was so stricken by the virus of inhibition that the first hint of radical departure from public wear was tentative. In September, he declared that he would wear a loincloth, without a vest, for just five weeks.

In October, Gandhi was in Madras, the city where more than a quarter century before, on October 26,1896 he had lashed out at the White racism then deeply ingrained in South Africa: “We are the ‘Asian dirt’ to be ‘heartily cursed’, we are ‘chockfull of vice’ and we ‘live upon rice’, we are ‘stinking coolie’ living on ‘the smell of an oiled rag’, we are ‘the black vermin’… we ‘breed like rabbits’ and a gentleman at a meeting lately held in Durban said he was sorry we could not be shot like them.”

A quarter century later Gandhi had challenged British supremacism with an innovative and unprecedented weapon: through the peaceful mobilization of a class that had been exploited and abused by both the British and the Indian elites: the poor. Such non-violent class warfare was beyond the comprehension of the Raj. But Gandhi realized that his own identification with impoverished not be complete until he abandoned that visible girdle of entitlement: conventional attire. He had to eliminate class from his own clothes.

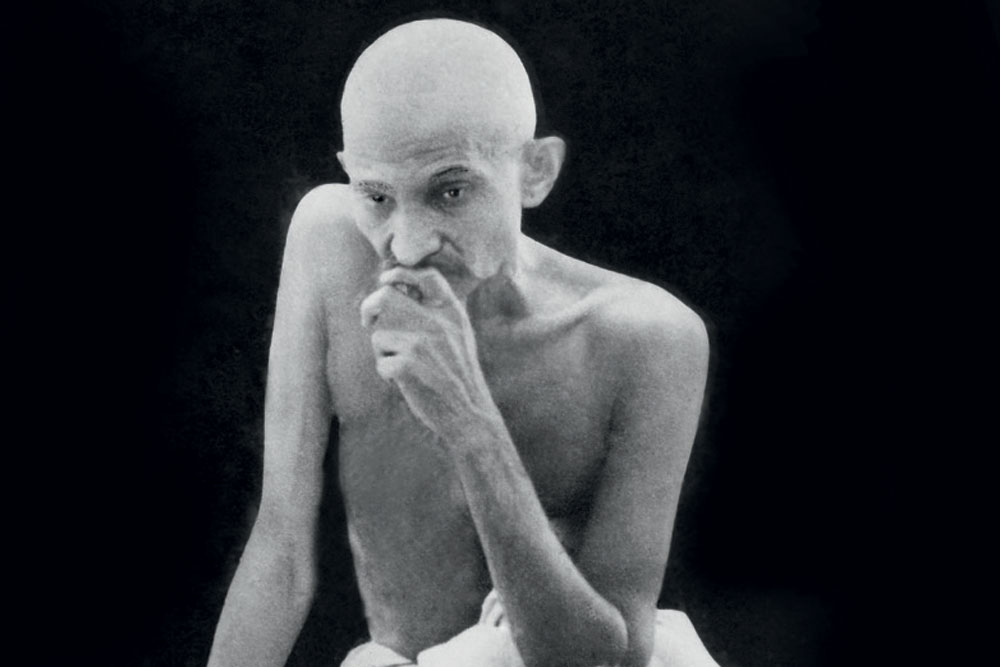

At 10 PM one night in October 1921, Gandhi had his head shaved. The next morning he went to address weavers, men who wove finery for their ‘betters’ but could not afford more than a strip of cotton for themselves. It was his first appearance in the avatar that quickly became iconic, an image on calendars and pamphlets that was worshipped in the homes of the poorest with an ardour reserved only for an architect of existential change. Those first tentative five weeks extended to a lifetime. Gandhi became the ‘betaaj badshah’, the king without a crown. From 1921 Gandhi lived and died in a loincloth.

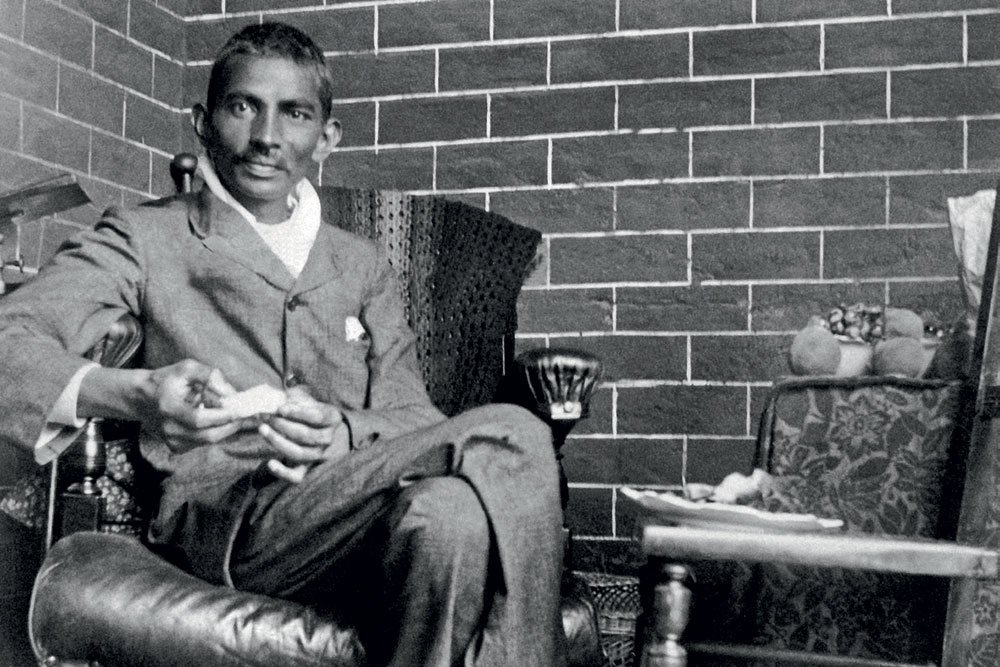

The evolution from England-returned lawyer to public ascetic was remarkable—and even revolutionary. In 1888, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, Esq, a student at London’s UCL Faculty of Laws, sported a Gladstone collar, rainbow ties, silk shirt, morning coat, double-breasted vest, striped dark trousers, patent leather boots, spats, leather gloves and a silver-mounted walking stick, while he learnt violin and dancing to improve his taste for Western mores. As a barrister in South Africa, his donned a frock coat and regal Indian turban.

The switch came after his resolute commitment to the emancipation of Indians, first in South Africa and then in India. By 1908, Gandhi had adopted the art of sartorial provocation as political strategy. Clothes became a metaphor for insurrection. His coat and trousers turned sloppy. He took to shirt and shorts made from Australian gunny sacks; his headgear became a black skull cap.

From 1911, he became an advocate, though not yet a prophet, of homespun. In one photograph, he is seen in a flowing kurta and lungi, holding a long lathi: the lathi became his familiar walking companion in India. He had not yet completely dispensed with his European attire. His eve-of-departure studio portrait taken shortly before he left South Africa in 1914 shows him in a suit beside his seated, sari-clad wife Kasturba.

Such suits might have still been required in cold London, where Gandhi stopped in 1914 en route India, but they disappeared once he berthed in Bombay on January 15th, 1915. He stepped on Indian soil in kurta, dhoti and Kathiawadi headgear. In 1916 at the Congress session in Lucknow, two richly dressed landlords mistook Gandhi for a peasant rather than a delegate. Gandhi was delighted.

The loincloth of 1921 provoked varied reactions. Some sympathisers worried, particularly as the dhoti got shorter, that Gandhi might turn ascetic and abandon politics. Others, more predictably, accused him of ‘indecency’. Gandhi’s response was forceful: “If we wear so many garments, we cannot clothe the poor, but it is our duty to dress them first and then ourselves, to feed them first and then ourselves… .” Homespun or khaddar became standard bearer of the Gandhian revolution.

The highest in the land and the mightiest in the world were not exempt from Gandhi’s logic. Of many similar instances, surely the most memorable is Gandhi’s encounter with King George V during the Round Table Conference in 1931, which the Mahatma joined as sole representative of the Congress. Gandhi sailed on August 29th with a ‘blank cheque’ to India’s minorities provided they come aboard the common platform to fight for independence from British rule. The response was lukewarm from sceptical Indian leaders at the conference; while the British Secretary of State, Sir Samuel Hoare, told Gandhi, with seeming sincerity, that Indians were unfit for self-government. Gandhi was seated next to Sir Samuel in recognition of his eminence, but his voice could not carry too far.

However, he was Gandhi. An audience with the emperor of India was proposed, with one caveat. Clothes. Could the Mahatma perhaps swaddle into something, er, a little more appropriate?

No. He had come, replied Gandhi, as representative of ‘Daridranarayan’, ‘the semistarved almost naked villager’, and he would dress like his principals.

His Majesty, a wise man, stooped to retain his conquest; Gandhi could come as he pleased. When, after the royal audience, the ever insatiable media asked if he had been adequately dressed, Gandhi famously answered that the king had worn enough clothes for both of them.

The conventional trajectory of a successful life measures achivement by acquisition. Gandhi needed less at every stage on his road to a momentous triumph, the fall of European colonialism. His foes, none more acid than the unrepentant imperialist Winston Churchill, dismissed such self-denial as humbug. Some of Gandhi’s admirers could also find him a bit indigestible. The poet-nationalist Sarojini Naidu’s jibe, that it cost a great deal to keep Gandhi in poverty, is an excellent throwaway party line in a sophisticated drawing room, worthy of Oscar Wilde, and very healthy too for the democratic spirit—for there is no democracy without satire. But the incomparable cartoonist, Sir David Low, was closer to the point when, in 1993, he caricatured British Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald ordering the stiff-upper-lipped Viceroy, Lord Willingdon, to go on a hunger strike against Gandhi. Gandhi’s abstinence seized the imagination of the world much before it inspired historic upheaval.

In the arsenal of Gandhi’s minimalism, hunger was an almost invisible weapon of last resort.

THERE IS SOME inner hermit in all of us. Normal humans spend a lifetime keeping it at bay or pretending it does not exist. A very few make their home in this hermitage. They are savants; those who ‘know’. They may be mystics, rishis, sages, poets, philosophers. But very rarely are they politicians.

The gods, perhaps as a continual test of temptation, made human nature an assertive element of the human being. Divine and eternal nature, said Gandhi, has provided enough for human need, but not enough for anyone’s greed. The elimination of greed and sublimation of need were continuous experiments in Gandhi’s definition of truth.

Even the hermit needs the three basics: bread, cloth, shelter—roti, kapda, makaan. Gandhi reduced cloth to a patch, and pared food to a tasteless paste.

Gandhi’s 17 fasts are famous, but he was on some kind of ingestion-denial all through his life. His single excess occurred when he was a schoolboy.

Gandhi, a child of the 19th century who became the father of the 20th, watched British power rise from dominance to omnipotence to what looked like invincibility for the first five decades of his life. Unlike most of his peers, Gandhi refused the smug comfort of fatalism. Even as a child he dreamt of ways to challenge and overcome foreign rule in his country.

One famous British Prime Minister wanted Gandhi’s fast to end in a form of suicide, after which he could wash his hands off this troublesome half-naked fakir. In 1943, Winston Churchill waited impatiently for Gandhi to die during his epic 21-day fast

In school he heard, from the teenage grapevine, a doggerel attributed to the Gujarati poet Narmad: ‘Behold the mighty Englishman/ He rules the Indian small/ Because being a meat-eater/ He is five cubits tall.’ To a schoolboy, size matters. Spurred by fantasies of physical strength and egged on by a mischievous companion, Gandhi began to eat meat, which was sacrilege to his faith and family and heinous to his beloved mother, Putliba. The boy was wracked with guilt and quickly abandoned this brief incursion into social and religious perversion. He developed such a passionate belief in vegetarianism that he rejected medical prescriptions which carried any suggestion of slippage. Gandhi details two instances in his autobiography. Once, when his wife Kasturba was seriously ill, the family doctor prescribed beef tea to strengthen her. Gandhi left the decision to his wife and was relieved when she rejected the option immediately. Life was meaningless without faith. As a younger man Gandhi was ready to risk the life of a beloved son wracked by very high fever rather than give him chicken broth as advised by the doctor. Gandhi nursed his son back to health with fervid prayer and personal attention.

A political confrontation made Gandhi a reductionist. In 1908, he was imprisoned during his famous satyagraha in South Africa. The rules permitted only White inmates to drink tea or coffee. Indians could add salt to their food, though not curry powder because, as the medical officer tartly noted, Gandhi had not been jailed to enjoy himself. Gandhi did not complain. Instead he gave up tea and coffee altogether and, for a decade, salt as well.

His doctrine was simple: “One should eat not in order to please the palate, but just to keep the body going.” By 1912, both his body and his soul had tired of milk, since he had been told it stimulated ‘animal passions’. He began to crave for abstinence rather than sustenance. He turned into a ‘fruitarian’, subsisting on raw groundnuts, bananas, dates,lemons and olive oil.

When he sailed for London in July 1914, the considerate captain of the good ship Kinfauns Castle, laid on a plentiful supply of fruit and nuts for the special passenger. This was a South African’s gesture of homage to an unusual hero.

The philosophy of Gandhi’s fasts lay in the second chapter of the Bhagavad Gita: ‘For a man who is fasting his senses/ Outwardly, the sense objects disappear,/ Leaving the yearning behind; but when/ He has seen the highest,/ Even the yearning disappears.’

The Mahatma went on a fast 17 times, 15 of them in India. Only one fast, during his detention at the Aga Khan Palace in Pune between August 1942 and April 1944, was in protest solely against the British policy. The rest were efforts to awaken Indians first and the government later; or, in times of communal strife, bring them back to their senses. It was always less a question of calories and more a test of will: would Indians change before Gandhi’s body surrendered? Gandhi never broke a commitment once he had made it. It was up to Indians to ensure that he survived. They never let their Mahatma down. In contrast, one famous British Prime Minister wanted Gandhi’s fast to end in a form of suicide, after which he could wash his hands off this troublesome half-naked fakir.

In 1943, Winston Churchill waited impatiently for Gandhi to die during his epic 21-day fast. His brutal cynicism was not shared by every senior official in the imperial administration. Major General Ronald Candy, Surgeon General of the Bombay government, remained a doctor of integrity through that arduous month of February, refusing to either misread the health condition or mislead the world when Chruchill wanted to spread the canard that Gandhi was a cheat, and was taking glucose secretly. A civil servant, Sir William Lewis, Governor of Orissa, understood what Gandhi meant to his people: Indians, he reported to the Viceroy, Lord Wavell, believed that their saint would never die; something would happen to end the fast before it became fatal. He added a warning: If Gandhi did die, vast outrage would follow—quickly.

Churchill was as petulant as a homicidal bully when Gandhi survived against all expectations. Dr BC Roy, Gandhi’s personal physician, later remarked, “He was very near death. He fooled us all.” Leo Amery, Secretary of State for India, congratulated Wavell for “your most successful deflation of Gandhi”, but knew his territory well enough to recall what the poet Lord Byron had said about his ailing mother-in-law: she had been dangerously ill; now she was dangerously well.

Gandhi’s own reaction after a fast that had reduced his weight from 110 pounds to 90 pounds, was to thank his medical team and then add, “I do not know why Providence has saved me on this occasion. Possibly, it is because He has some mission for me to fulfil.”

Thanks to memoirs written by Pyarelal, his secretary after the sudden death of Mahadev Desai on 15 August 1942, and Nirmal Bose, the Calcutta University academic who joined Gandhi during his epic tour of Noakhali between November 1946 and the last day of February 1947, we have firsthand accounts of Gandhi’s daily routine. He woke up at four, brushed his gums with twig and dental powder, heard a recitation of the Gita and then ate a breakfast of three small spoonfuls of honey, five grammes of baking soda and a glass of fruit juice.

This was followed by a mile-length walk, which might include stops for chats with villagers or to hear chants from the Quran from children at a madrasa. He shaved on alternate days and was thrifty with blades. When a Christmas gift of cigarettes and razor sets arrived from South Africa, Gandhi kept the shaving equipment and passed on the cigarettes to Jawaharlal Nehru, who enjoyed smoking. Gandhi’s early lunch consisted of eight ounces of goat milk, an ounce of fresh lime and a saltless, spiceless vegetable paste which the rest of his entourage found thoroughly inedible. The last meal of the day, at 3.30 in the afternoon, was similarly sparse.

His menu was vegetarian, utilitarian and minimalist, but Gandhi never imposed his frugal fare on others. Since Bengalis eat fish, he was once asked, mischievously, whether killing fish was violent or non-violent. His answer was dismissive. Bengal was a land of water, so what was the harm in people eating fish? In any case, eating fish was less harmful than selling adulterated food. Bengal in 1946 was still waking up from the devastating wartime famine which had taken between three and four million lives and enriched hoarders.

The saint could be sarcastic with any wiseacres.

MOHANDAS was born in a mansion, albeit an impecunious one, a century-old three-storeyed residence of officials who had served the small princely states of Kathiawad in Gujarat. When there were guests, his father, Karamchand or Kaba, helped by peeling vegetables. Gandhi learnt integrity from his father and religion from his mother, Putlibai. One of the rewards of success as a lawyer in South Africa was an impressive bungalow in Natal. But the inner churn of those years was taking him towards a very different ideal. In April 1895, he was deeply impressed after a visit to a community of Trappist monks living at Mariam Hill near Pinetown, 16 miles from Durban, in renunciation and poverty. It helped that they were also vegetarian. Gandhi wrote about their republican principles and community welfare in a subsequent issue of a publication called The Vegetarian.

This was a modern model of Tapovan, abode of austerity, the Vedic ideal. By 1904, with the influence of Tolstoy and John Ruskin now layered into his thinking, Gandhi created the Phoenix Settlement over 100 acres in the picturesque Piezang Valley, 16 miles from Durban. His own living space was comparatively modest, but not spartan: a living room, two small bedrooms, a tiny kitchen plus a literal shower (a string pulled open a watering can above from which water sprinkled down).

Gandhi’s fame had preceded him when he returned to India. There were glittering receptions by the high and mighty of Bombay’s elite and more subdued acknowledgement from Charles Hardinge, 1st Baron Hardinge of Penshurst, Viceroy between 1910 and 1916. What Gandhi did not possess was a home.

Gujarat was a natural preference for a Gujarati. Moreover, he could count on some financial assistance from Aurangabad’s industrialists for his abstemious requirements. His first ashram at Kochrab, over 36 acres, was founded on May 25th, 1915. On the one side, Gandhi commented ruefully, were the iron bolts of the British and, on the other, the thunderbolts of nature. The space was full of snakes but Gandhi was always at peace with nature. His instructions were clear. Not a single snake would be killed.

In July 1917, Gandhi shifted to the banks of Sabarmati, where he seemed to have found a lifelong abode. But any such ascertainment must take into account the epiphany of a Gandhian vow. More than a dozen years later, on March 12th, 1930, Gandhi began his historic Salt March from his Sabarmati ashram with a promise: he would not return until India was free.

The optimism was heady, but unjustified. On the morning of January 4th, 1932, Gandhi was arrested “for good and sufficient” reasons in Bombay. When Gandhi saw Police Commissioner Wilson and his deputy Khan Bahadur Pettigara, he smiled. Kasturba, in tears, begged the police to take her as well, but they had no instructions to oblige. Gandhi’s face was wreathed in smiles as he headed towards Yerwada Jail. He was released at 6 PM on May 8th, 1933, just as he was about to go on a fast. He was back in jail on August 1st the same year as he prepared to go on another march. The government was totally uncertain in its responses. On 4th August the authorities ordered release, but this time Gandhi refused to comply. He was eventually freed on August 23rd because of health conditions. He now had to find another permanent home, at the age of 65.

One famous British Prime Minister wanted Gandhi’s fast to end in a form of suicide, after which he could wash his hands off this troublesome half-naked fakir. In 1943, Winston Churchill waited impatiently for Gandhi to die during his epic 21-day fast

In 1934, a devotee-industrialist Jamnalal Bajaj took Gandhi to his bungalow in Wardha, Bajajwadi. Gandhi chose a village, Segaon, about eight km away, as his next abode; the ashram formally opened in 1936. Small huts were constructed for inmates.

A local guru, Gajanan Maharaj, lived a short distance away in a place called Shegaon. Quite a bit of Gandhi’s mail kept getting diverted there. In 1940, Gandhi renamed his own ashram Sevagram, or village of service.

It was also among the hottest spots in India. When in the weeks prior to the launch of the Quit India movement, Gandhi began to give interviews to prepare international opinion, he invited journalists to stay at Sevagram and gave them time in the afternoon: during the hottest part of the day of the hottest month of the year (June) in the hottest place in India.

Louis Fischer, son of a fish seller, former schoolteacher, member of the Jewish Legion based in Palestine, correspondent from Moscow in the Stalin era and now on the staff of the left-leaning American weekly paper, The Nation, would go on to write a biography of Gandhi that is still in print. A blistered Fischer asked the Mahatma if they could schedule their next round of interviews in an airconditioned place—perhaps the Viceroy’s palace? Gandhi, tongue firmly in cheek, replied that he would give the suggestion due consideration. The hermit had a relaxed sense of humour.

Was Gandhi also joking, or perhaps speaking half in jest, when he said that there was no lofty principle involved in his weekly vow of silence? Gandhi never spoke on a Monday. During Monday meetings he would scribble down his answers. The last Viceroy, Lord Mountabatten, once gathered stubs of such scribbles in the belief that they would have historical value.

Gandhi told Fischer that there was no great monastic purity about it; he simply wanted some respite from conversation. “Later,” he added, “of course I clothed it with all kinds of virtues and gave it a spiritual cloak. But the motivation was really nothing more than that I wanted to have a day off. Silence is very relaxing.”

Even in conversation less can be more. Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, father of India’s freedom, was more eloquent in his silence on August 15th, 1947, than any oratory could have conveyed. Despite the raw barbarism of the spreading communal riots that accompanied Partition, there was an explosion of joy when the Tricolour replaced the Union Jack. But Gandhi remained silent.

The information department of the government asked the Mahatma for a message to be broadcast on August 15th. Gandhi had none. He was told this would be ‘kharaab’, or bad. Gandhi was curt: “Hai nahin koi message; hone do kharaab [There is no message; let it be bad].” When BBC approached him, Gandhi wrote on a piece of paper: “I must not yield to temptation. They must forget that I know English.” His reason? This was not the swaraj Gandhi had given his life for. He had dreamt of a free and united India, not one partitioned by Jinnah’s bloodstained scalpel.

Gandhi recognised the reality, but he would not accept this monstrous madness which had ripped apart the civilisational unity of India and institutionalised a partisan difference into a communal divide. When, at the famous stroke of the midnight hour, India won freedom, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, visionary and unquestioned inspiration of the freedom movement, was fast asleep.

Silence, isolation dislocate us. For countless generations we have equated civilisation with the creative juices of community and solitude with either the abdication of the monk or, more often, with punishment, penance or ostracisation. The child stands in the corner at school or perhaps used to; the adult suffers the consequences of a penal code.

The great rishis of Indian belief achieved their powers through isolation. Even normal mortals could attain boons with sacrifice and devotion. Sagara, king of Ayodhya, spent 100 years as ascetic praying for an heir; but his efforts to persuade the Goddess Ganga to descend from heaven and emancipate his 60,000 unruly sons failed even after 30,000 years. It was not until Bhagirathi, his great grandson, stood for 1,000 years that Brahma granted this wish. There were more trials until Ganga coursed through Shiva’s locks and wound her way to the sea, which was dry because the iconic sage, Agastya, had drunk the waters of the ocean. Ganga’s water replenished the seas and restored the balance.

Who could be more sagacious than Agastya, author of 26 hymns of the Rig Veda? His advice to Lord Rama remains the axiom of life as we lead it: ‘Rama, demons do not love men, therefore, men must love each other.’

Never more so when a demon virus has driven cities and villages across the world into isolation.

What did Gandhi, who lost his private life when he became a public personality, do when forced into the isolation of a British prison, cut off by barbed wire and armed soldiers during his 18-odd months at the Aga Khan Palace-prison?

Gandhi filled a number of hours with routine: prayer, spinning, newspapers, letters and teaching his 15-year-old grandniece Manu, who had become Kasturba’s ward. But the serene story of this period is the joy of his relationship with his ‘life companion’ Kasturba. She cared for him with a fierce protectiveness, even if occasionally scolding him for sending everyone to jail. They would sing songs together at night. But age was not on the side of Kasturba. After more than a year together, in December 1943, she suffered three heart attacks. Gandhi demanded Ayurvedic treatment, which her body was attuned to. By the time Vaidraj Shri Shiv Sharma was permitted to see her, it was too late.

On February 22nd, 1944 at 7.35 PM, Kasturba passed away, her head in Gandhi’s lap. Thirty-two minutes later Gandhi wrote to the government hoping it would show better grace in handling her funeral than it had shown during her illness.

There was international outrage at the fact that she had not been released on medical grounds even after her heart attacks. In London, Churchill’s minister RA Butler told Parliament on March 2nd, 1944 that all possible medical care had been provided, which was incorrect. In Washington, British India’s agent Girija Shankar Bajpai tried to assuage public opinion by claiming that Kasturba had wanted to stay with Gandhi, which was a blatant lie.

One ironic consequence was that when Gandhi came down with malaria the following month, he was released with near-comic haste.

None of us can be Gandhi. But you don’t have to be Christ to become a Christian. Perhaps isolation offers an opportunity to have a brief chat with that elusive inner hermit. It just might have something to whisper.

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover_Dalai-Lama.jpg)

More Columns

India’s First Vision-Only Autonomous Car Was Built for Chaos Open

Trump Restarts Tariff War With the World Open

‘Why Do You Want The Headache of Two Dalai Lamas’ Lhendup G Bhutia