Kashi Vishwanath Temple: The Grand Makeover

One no longer has to crane one’s neck to see the Kashi Vishwanath Temple. It now has ample breathing space and can be viewed from afar. The ₹ 900 crore Kashi Vishwanath Dham project is being executed against great odds

/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Makeover.jpg)

Work underway at the Kashi Vishwanath Temple Vomplex, 25 February 2019 (Photos courtesy: HCP Design Planning and Management)

ON THE DAYS OPEN visited the Kashi Vishwanath temple corridor in Varanasi, less than a fortnight before the first phase of the ambitious project was inaugurated by Prime Minister Narendra Modi on December 13th, work was in full swing with backhoe loaders, dump-trucks, excavators, cranes, JCB heavy equipment and other construction machines from companies as varied as Tata, Hitachi, Heritage Infraspace and others competing with labourers to finish the work at a frenetic pace.

Officially known as the Kashi Vishwanath Dham project, undertaken by Shri Kashi Vishwanath Special Area Development Board (SKVSADB), the redevelopment saw the demolition of 314 buildings, which had housed at least 1,400 shops besides illegal squatters. Varanasi Divisional Commissioner Deepak Aggarwal, who is also the chairman of the Kashi Vishwanath Temple Executive Committee, tells Open that the early demolition target was 197 buildings, but the scope of the work expanded as they discovered new temples since the prime minister’s laying of the corridor’s foundation stone in March 2019. “It happened as we progressed with the work,” he admits. A total of 78 temples were discovered before and during the construction process. The ancient city of Varanasi—home to seers as iconic as Adi Shankaracharya—is also the prime minister’s Lok Sabha constituency. Mark Twain, who had visited this city, had remarked in his Following the Equator: A Journey Around the World: “Benares is older than history, older than tradition, older even than legend, and looks twice as old as all of them put together.” Such is the fame of the city that continues to thrive even after centuries.

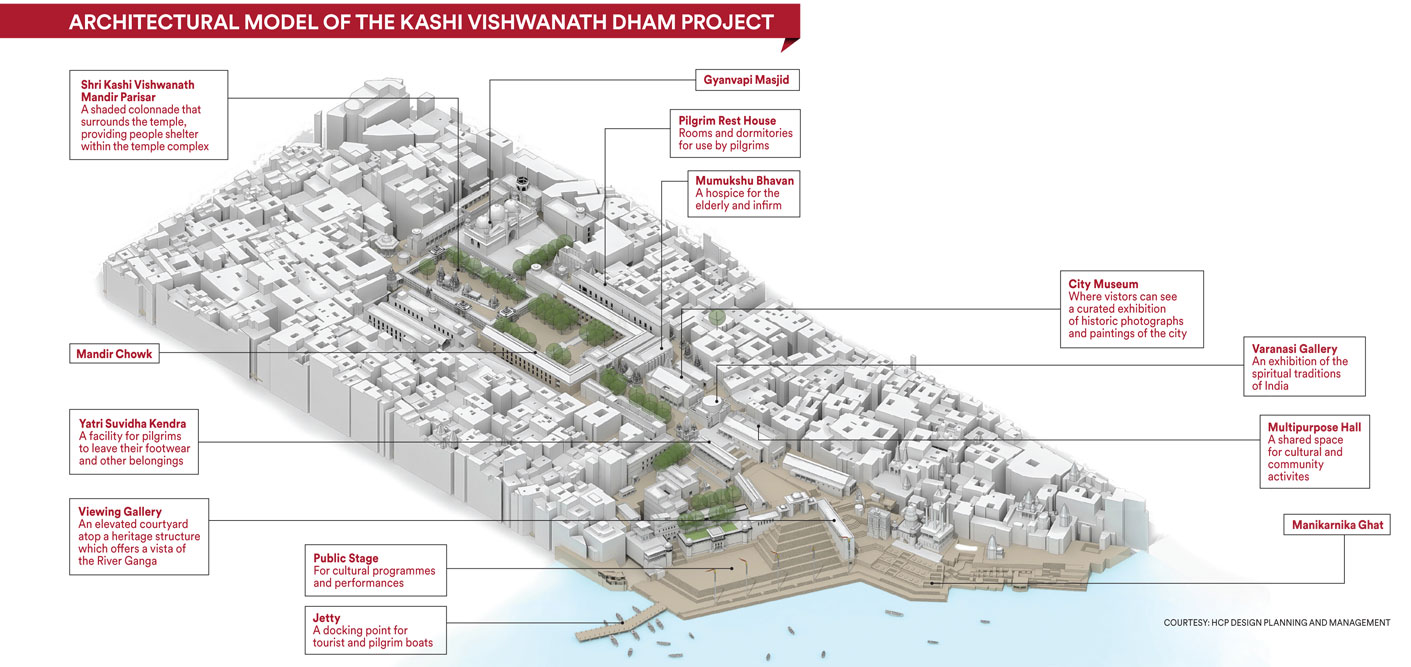

From a mere 2,700 sq ft in 2019 and prior to that, the temple complex is now a sprawling compound measuring upwards of 5 lakh sq ft, connecting the Ganga at Lalita Ghat, where a jetty is expected to come up, to the bustling road near the Chowk. The facelift is nothing short of monumental considering the glitter it gets from a generous use of red sandstone, Chunar stone, Kota granite and Makrana marble. The ghats in the vicinity, apart from Lalita Ghat, are Manikarnika Ghat, considered the holiest of all cremation grounds by Hindus, and Jalasen Ghat.

Aggarwal adds that whoever wants to visit the Kashi Vishwanath temple, considered divine by Hindus and stands on the Western bank of the Ganga, doesn’t have to climb a single step any longer. “Keeping the elderly pilgrims and the physically challenged in mind, we are building escalators that can be used by anyone coming from the riverfront via dock boats to reach the temple. Earlier, devotees mostly used to enter the temple from the Godolia and Saraswati gates,” he states. The Kashi Vishwanath temple is one of the twelve Jyotirlinga shrines. The word, Vishwanath, stands for “the ruler of the universe”, or Shiva. Of the 64 known Jyotirlinga shrines, meaning devotional representations of Shiva, 12 are considered the most sacred. Aggarwal points out that the corridor, for which upwards of ₹ 900 crore is expected to be spent on completion, will have green cover in over 70 per cent of the whole area that has been redeveloped. “Mostly Rudraksha, Parijat, Ashok and Bael trees will offer the green cover,” he explains. These are the trees believed by Hindus to be Lord Shiva’s favourites.

The discovery of new temples also meant speedy conservation, which was managed by SKVSADB in collaboration with specialist consultants and contractors. Shivani Mishra, a Jaipur-based conservationist who has worked on these temples in the corridor, says that she and her team of 200 have so far completed conservation work at 17 of the 26 temples identified for restoration in this large complex. “The walls of most temples (including that of Kashi Vishwanath) were in extremely bad shape because of the paint used, besides decay, and we had to use various tools and work round the clock to finish whatever we have done so far,” says Mishra, adding that she didn’t use any chemicals for fear of further damaging the walls. “We cleaned and restored these temples using jaggery, fenugreek, custard apple, Guggul (dried resin of the Indian Myrrh tree) and similar organic ingredients,” says this head of JBN Exports, which, she adds, has worked with other temples in India, including the Somnath temple. The company also makes figurines and statues of gods using marbles. Mishra notes that she started working on this project—of which Gujarat-based PSP Projects is the contractor and Ahmedabad-based HCP Design, Planning and Management Private Ltd the architect—only since July 21st this year. The work on the corridor had begun two years ago, but had to be stopped midway because of the Covid-induced lockdown. The work was resumed last year employing at least 1,200 labourers. Mishra, meanwhile, says that she hopes to finish the rest of her work over the next two-and-a-half months.

As one paces the corridor from the ghats to the Kashi Vishwanath temple, the ease of movement is quite a different experience in this city also known as “galiyon ka shahar (city of lanes)”. Compared with earlier visits that often meant getting lost, before you finally made it to the temple after several enquiries, temple trips are going to become less cumbersome. While some people are nostalgic about the past and what they call the quintessential Banarasi way of life, many others feel that with the number of visitors soaring every year, more arrangements for pilgrims are in order. Aggarwal argues there was hardly any resistance from homeowners, shop owners and squatters in the area because everything “was done in a mutually agreeable manner”. Sellers of properties were paid twice the market rates, he declares. The prime minister keenly followed each step of the redevelopment of the temple premises, says Aggarwal. In fact, Modi got a model of the Kashi Vishwanath temple corridor made at his residence to regularly review the progress of the project.

The problem with not doing a revamp of the main Shiva temple area, Aggarwal argues, is that pilgrims who come from afar hardly get much time to spend more than a few minutes at the temple complex. That is disappointing for most people who make such long journeys. Which is why, this redevelopment was the need of the hour. Last year, more than seven million people visited the Kashi Vishwanath temple. Compared with only a few hundred at a time earlier, the complex can now accommodate more than 75,000 people at a time. The length of the temple corridor starting from the ghats to the temple is 400m, with a width of 75m.

THERE IS GOING to be more order and less chaos at the temple from now on, officials insist. The new facilities at the temple complex include pilgrim facilitation centres with lockers where visitors can deposit their personal belongings and footwear, dormitories for pilgrims, museums, cafés, a communal kitchen, a hospice for the elderly and infirm, galleries, a multipurpose hall for cultural and community activities, a viewing gallery, a spiritual bookstore, security arrangements, a guesthouse and so on. The corridor is also armed with more than 300 CCTV cameras and baggage scanners.

The Chandragupth Mahadev temple just outside the newly christened Mandir Chowk, the last gate at the Kashi Vishwanath temple for those coming from the ghats, looks stunning after it has been restored. It is one of the many other temples that have found a new life after their near-obscurity in a place that was called Lahori Tola. As the description goes, “This temple is a mirror image of the main Vishwanath Temple. It was built by King Chandragupta during the Gupta era. It is believed that the very sight of the deity fulfils one’s wishes, hence the temple is also known as Manokameshwar Mahadev Temple”. Another attraction near the Mandir Chowk gate is, of course, the ‘viewing gallery’ on the second floor. The lifts of the building are state-of-the-art and the floors are shining. From its vantage point, one gets a clear view of both the Ganga and the main Vishwanath temple. It is indeed a photographer’s boon to be up there when the complex is packed, as the ghats and the temple appear quite near.

The Kashi Vishwanath temple is no longer the shrine where one had to crane one’s neck to even see the temple, forget the deity. It now has ample breathing space around and can be viewed from afar. Its gold-coloured dome shines better. The new Parisar (the sacred ground around the temple) is made with the same stone used to make the temple. The vast space now available around the main temple allows devotees more time to get a view of the deity and even take rest. According to SKVSADB, thanks to redevelopment, the Parisar “is enclosed by an ornate colonnade and approachable from four decorative gateways. The colonnade and gateways use traditional motifs of Hindu Architecture and are constructed entirely from local Chunar stone, without any steel or concrete reinforcement.”

There is going to be more order at the temple from now on. The new facilities include pilgrim facilitation centres with lockers, dormitories, museums, cafés, a hospice, a viewing gallery, a spiritual bookstore, a guesthouse and so on. Also 300 CCTV cameras will be in place

The official explanation given for constructing the massive corridor around this temple is that “it [the main temple] was hemmed in on all sides by very dense and haphazard development. The many temples and fine houses in the area were insensitively built over. Public spaces were encroached upon. The area became very difficult to service and keep clean and the access to the temple was severely constricted”. Again, the official word on the redevelopment is that the new “precinct provides a befitting setting to the Kashi Vishwanath Temple and upgrades this special spiritual destination in Varanasi for pilgrims and tourists. A picturesque path running through the centre and lined by many cultural and civic amenities connects the Temple and the Ganga River”. Both the contractors and the architects of this project have done multiple government projects. PSP Projects Ltd’s website lists the Sabarmati Riverfront Project as one of its marquee projects. Besides many others, the Bimal Patel-led HCP Design, Planning and Management Private Ltd is handling the ambitious redevelopment of New Delhi’s Central Vista, inspired by Washington DC’s Capitol Complex and Paris’ Champs-Élysées.

Patel tells Open about his early impressions of the Kashi temple project after his company was awarded the proposal to make the master plan for its staggering revamp. “It is impossible to arrive in Varanasi and not be first struck by its charms and character. However, on deeper inspection, we realised how dense the area was, and how difficult it was to access this particularly important temple. While charming and full of character, the urban fabric would need to be altered for the temple to work well,” Patel says. He adds, “Varanasi, although ancient, is composed of many layers of blended architectural styles. A new typology of buildings and urban spaces was needed that served the temple well and also blended with the context.”

Patel also adds that the most helpful inputs for the redevelopment came from the people on the site, members of the Shri Kashi Vishwanath Temple Trust and representatives of the Varanasi district administration. “These were the people who understood the ground reality extremely well,” states Patel, who has handled several of Modi’s pet projects. An alumnus of Berkeley CED, Patel is president of CEPT University in Ahmedabad.

As regards the ongoing project that has attracted wide attention thanks to multiple reasons, Patel says a lot of precautions have been taken to ensure a Banarasi touch to the complex. Notwithstanding criticism from certain quarters, including architects and locals, Patel quips, “Much care is being taken to ensure that the additions here fit well with the surrounding area.”

He adds that the corridor, once it is complete, will be “an architectural expression of a journey towards self-discovery”. That sounds apt indeed for the central attraction in India’s holiest of holy cities.

Interview: Bimal H Patel, architect

‘Kashi Corridor is the architectural expression of a journey towards self-discovery‘

Bimal H Patel is one of India’s most reputed architects. He also handles some of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s pet projects. The man behind the Central Vista project spoke to ULLEKH NP about the Kashi Vishwanath Temple Corridor project which, he says, was different from all his previous assignments because of the logistical challenges in one of the world’s most ancient living cities. Patel, president of CEPT University in Ahmedabad, heads HCP Design Planning and Management.

When did the proposal for the Kashi Vishwanath temple corridor land on your desk? What was your immediate response?

The Vishwanath Dham proposal was awarded to us in late 2018. The process of acquiring properties for building the corridor had already started by then. Our first response was that it was a challenging task, and that this proposal would require careful thought and a deep understanding of the context. A new architectural vocabulary needed to be developed that would provide a befitting setting to the temple, enrich the neighbourhood, and merge with the urban fabric of the city.

Who were the key people you held discussions with before drafting the master plan?

We had several discussions with different stakeholders and specialists before we designed the master plan. This included architects who specialised in temple construction, representatives of the Shri Kashi Vishwanath Special Area Development Board, local residents in the area and others.

How many times did you have to revise the master plan based on new inputs and discoveries, for instance, of new temples?

We revised the master plan several times, for three reasons: One, many temples were unearthed from within private houses during construction. These were restored, in consultation with a conservation architect and included in our design, enriching it greatly.

Two, the master plan was revised again when new properties and additional space became available to us.

And finally, when we discovered the possibility of creating a memorable ghat and a gateway on the banks that would make the temple’s presence felt. Our design also ensured that the privacy of mourners at Manikarnika Ghat was protected.

Which were the texts you relied on to know more about the area where the corridor has now come up?

We referred to several books about the city, including the classic works of Diana Eck (Banaras: City of Light), James Prinsep (Banaras Illustrated), Amita Sinha (Ghats of Varanasi on the Ganga in India: The Cultural Landscape Reclaimed) and Madhuri Shrikant (Banaras Reconstructed).

Did you get hold of any watershed works so you could fall back on them to know about early temples in this region? How did you tap traditional knowledge about the place? Did you consult the works by Pt Kuber Nath Sukul, for instance?

We did not do anything to the temples themselves other than cleaning them up and integrating them well with our master plan. Therefore, we did not need to tap traditional knowledge about specific temples. Our design dealt with the buildings and facilities around the temples.

What were the precautions taken to ensure there is a Banarasi touch to the new corridor?

The temple and the redeveloped precinct are a very tiny portion of Varanasi.

The temple Parisar (surroundings) was made entirely in Chunar stone from Mirzapur, which is the same stone used in the temple, that adds a Banarasi touch. The outer court, the temple Chowk, is modern yet uses traditional arch-shaped torans (gateways), to blend in with the temple architecture. The gateway to the Chowk draws inspiration from the Ramnagar Fort gateway. The rest of the buildings, including new pilgrim facilities that have been added, are modern and functional buildings that match the bulk and height of the surrounding development.

New architecture in any ancient city always generates a discordant note, however feeble. Did you face any such criticism from the locals or other architects?

We did receive some criticism from conservative architects and commentators who seemed to suggest that all change is problematic, and everything is worthy of preservation. Such criticism was not very helpful in addressing any of the practical problems we were trying to resolve, such as the provision of facilities, infrastructure, space, etcetera.

Sewerage systems may have been non-existent in this area. What was done to revamp the place and manage solid waste?

There were extant sewage lines and an active sewage pumping station at Lalita Ghat, which is currently in the process of being relocated. We have used the same to manage solid waste from the project precinct.

What will the final plan look like? Is it meant to ensure entry to the temple corridor from the Ganga or are there alleyways also being developed to let devotees and tourists in?

The final plan is, in essence, the architectural expression of a journey towards self-discovery.

From the river, the temple’s presence is announced by a gateway atop a pyramid of steps. Thereafter, the Chowk, which is centred on an axis with the gateway, guides one towards the temple. From there, one descends to reach the gateway of the Parisar, which is also centred on the same axis. The experience of the pathway is, in a sense, a slow unfolding of self-realisation.

The approach from the Ganga will be the primary access to the temple. However, all the present access routes from the city will also remain functional and accessible.

When do you expect to finish this project?

The main temple precinct is ready and was inaugurated on December 13th. The ghat area will be completed in another three months.

How challenging or different was this compared with the other projects you have/had undertaken?

The construction of the project was a huge logistical challenge because the only access for transporting construction material was either through a narrow 40 feet road that reached one end of the site or on barges on the river. Much of the demolition had to be done manually because of the space constraints.

How many people can be accommodated at the guest house inside the complex?

The Mumukshu Bhavan, a place for people who choose to spend their final days in Kashi, will have the capacity to host 50 people at a time. The guest house will have 18 rooms.

/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Cover-War-Shock-1.jpg)

More Columns

Tiger’s World Open

Heroism of the Ordinary Kaveree Bamzai

Mr Bodacious Meets Ms Bossy Pants Kaveree Bamzai