The Pursuits of the Past

IS HISTORY AN enquiry into the past? Or is it a pedagogic tool to instil ideas of progress and development and thereby strengthen the nation state in its endeavours? Or, indeed, is it actually another critical way of examining ourselves in relation to our pasts? Historians, governments, public figures and lay citizens have grappled with these questions, often unconsciously, but also frequently head-on. The University Grants Commission (UGC) has recently ventured into this minefield and come out with a new template for undergraduate history teaching and syllabi. Its first sentence is: "History, as we well know, is a vital source to obtain knowledge about a nation's soul". To many this seems to sum up comprehensively the ongoing history wars sweeping India and those which are forthcoming. While public figures and intellectuals of the past and present have spoken of India's 'soul', historians have been more circumspect. The litmus test for any history is the doctrine or regimen of evidence; harnessing evidence to establish a soul or a single thread that is clearly identifiable through our entire history is an impossible undertaking.

A more reasonable approach may well be to try and explain how the past comes down to the present and then looks onward to the future. Even here, assessing the precise weight of the past is not easy. In an essay 'Beyond the Modes of Thought', in his 1922 collection on the Gita,

Sri Aurobindo appears to be exploring or asking about how the weight of the past impacts and interfaces with the present: "We speak and act as if we were perfectly free in the pure and virgin moment to do what we will with ourselves using an absolute inward independence of choice. But there is no such absolute liberty, our choice has no such independence".

It's the Pits!

13 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 58

The state of Indian cities

Jawaharlal Nehru, reading these lines, certainly saw these thoughts as constituting questions on how our history weighs on us—leaving us seemingly free but in fact not so. In The Discovery of India, he described Sri Aurobindo's "pure and virgin moment" as that "razor's edge of time and existence which divides the past from the future, and is, and yet, instantaneously is not". To Nehru these divisions of the past and the future by the present raised questions impossible to answer: "The virgin moment emerging from the veil of the future in all its naked purity, coming into contact with us, and immediately becoming the soiled and stale past. Is it we that soil and vitiate it. Or is the moment not so virgin after all, for it is bound up with all the harlotry of the past".

A little over two decades earlier, incarcerated in Yerawada jail, Mahatma Gandhi also wrestled with the nature of history, history writing and the weight of the past. He saw his jail term as an opportunity to educate himself by reading, which his hectic activity in public life had otherwise left little time for. So, apart from reading books on philosophy and religion, improving his Sanskrit, teaching himself Urdu and Tamil, Gandhi had also plunged into Edward Gibbon's History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.

This had been recommended to him years earlier and Mahatma Gandhi wrote in 1924: "I was determined to read Gibbon in the jail this time" in part also because "he [Gibbon] is a historian jealous of his calling, faithful enough to give you all his data so as to enable you to judge for yourself". Gandhi's own views about historical methodology are also worth recalling: "the dividing line between fact and fiction is very thin indeed…even facts have two sides or as lawyers say facts are after all opinions." He probably saw no easy way out of the question Nehru posed—of choice trapped between past and future and when it is impossible to say whether Aurobindo's "pure and virgin moment" of the present is sullied by the past, the future or by itself! Mahatma Gandhi's conclusion, if it can be called that, is equally striking: "I believe in the saying that a nation is happy that has no history".

Which nation would that be in which the past does not intrude upon the present and shape the future? Mahatma Gandhi himself in the 1920s would have found it difficult to identify one. In India, the Khilafat Movement had ended in disappointment and communal antagonisms were intensifying. The shadow of the Great War in Europe—revolution in Russia, counter-revolution in Germany, the carving up of the remnants of the Ottoman and the Austro-Hungarian empires by the victors and others—and the rise of a new imperial force in the East in the form of Japan. None of this suggested a "pure and virgin moment" but instead that the baggage of the past in each case would also prove to be a faultline in the future.

It is useful to see the Indian debates on its history in the wider context of conflicts on similar sets of issues and in particular how history writing or the teaching of history has to be reconciled with one idea or set of ideas of the nation. The discussion about racism and slavery in the US is well known and is frequently commented upon. That intellectual debate has been matched by street-level movements and protests, such as those that followed the killing of George Floyd in May 2020 and added a new intensity also to the existing demands for removal of the statues of Confederate generals and political leaders who had fought for the retention of slavery in the US Civil war of the 1860s. Here, the battlelines are clearly drawn, almost as if that war had not been fought and the issue still remains to be settled.

Is the spirit or the 'soul' of the US, as reflected in its constitution, the idea of an expanding idea of freedom as a core value that explains the American way of life? That dominant narrative is increasingly questioned by scholars and activists alike who point to the unresolved issues emerging from slavery that remained embedded in the US constitution despite the bitterly fought and bloody Civil War. In this counter-narrative, racism and discrimination are as intrinsic to the American way of life as ideas of democracy and freedom. Such revisionist readings in turn consolidate and inspire majoritarian white counter-reactions. Many states in the US prescribe school history syllabi that dilute, if not prohibit altogether, teaching of issues arising from the history of slavery and the bitterly contested terrain of race relations. In some states, it is prohibited to teach anything that would give rise to feelings of "discomfort, guilt, anguish or any other form of psychological distress on account of an individual's race or sex". Thus, teaching anything which upsets one particular and prevalent reading of the past gets debarred.

To the distinguished historian of totalitarianism and of European history, Timothy Snyder, this is the US variant, even as it is opposite to Europe's 'memory laws'. The latter have their antecedents in Holocaust denial in Germany where it is a criminal offence to deny that there was a systematic extermination of Jews by the Nazis. Such memory laws today sweep across parts of Europe and Russia but in different, almost perverse, variants that essentially seek to suppress all that is uncomfortable to current perceptions of national self-esteem. Thus, in Russia today there is a ban on "false information on the activities of the Soviet Union during the second world war". This, in effect, precludes examination of even well-known issues such as the Nazi-Soviet pact or their joint invasion of Poland, or in fact anything that could infringe the grounds that "it is wrong to insult the memory of the victorious nation".

In Snyder's analysis, there is in many ways a convergence between the US and Russia with regard to the teaching of history. The systemic differences between the two with regard to historical research or the substantial freedoms that universities and academics enjoy in the US should not, however, be discounted. The general point is that debates about older faultlines continue with an added intensity with little consensus on fundamental issues of "whose history" or "how is history to be taught and written".

The massive social engineering by the Soviet Union in the form of collectivisation of its agriculture and the famines this led to is for post-Soviet Ukraine a 'genocide' perpetrated on it. For post-Soviet Russia, on the other hand, any such talk is aimed at widening the already vast geopolitical gulf between the two countries. In Europe as a whole, anti-Semitism, racism and colonialism remain tied to its present as indeed they stalked its past. In the US, slavery may technically have ended but research into its various dimensions is profoundly impacted by current debates on race relations and white supremacist views on US history. A world tour of history writing and teaching would reveal similar debates elsewhere.

THIS BROADER CONTEXT to its own history debates can provide munitions to defensive whataboutery in India to criticism against what is now an unmistakable trend towards straitjacketing of history writing and teaching represented by the 'soul of the nation' approach of UGC. Such is not the intention in this article. Each national experience is different and the point really is also to understand how inextricably history is tied up with the national project as a whole and what should be the role of the historian in this interface. This debate is not a new one and has occurred frequently in India from time to time. We get a sense of this from an episode in the career of RC Majumdar (1888-1980).

Majumdar remains best known for being the editor of one of modern India's most ambitious history writing projects to date—the Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan's History and Culture of the Indian People—a 12-volume set that appeared between 1951 and 1969. Majumdar had been a professor of history at the University of Dacca and thereafter its vice chancellor. He was highly regarded as a historian of ancient India in his time but post-1947 also immersed himself in studying the national movement and was appointed in 1953 as the head of a government project in the ministry of education to write the history of the Indian freedom struggle from British colonialism. An account of the events of 1857 was planned as the first volume in the series. Majumdar had frequent bouts of friction both with the official establishment as also with historians he believed were following the official 'line' in disregard of the actual historical record. Growing differences with the board of editors that was to supervise the project soon became evident and Majumdar wrote: "[As] soon as I was engaged in preparing the draft, I realised the difficulty of writing history on a co-operative basis in a non-academic environment, and on a theme round which strong emotions have gathered for years, and which involves, directly or indirectly, a judgment on the views and actions of persons who occupy, for the time being, high places either in actual life or in the estimation of an influential section of the people."

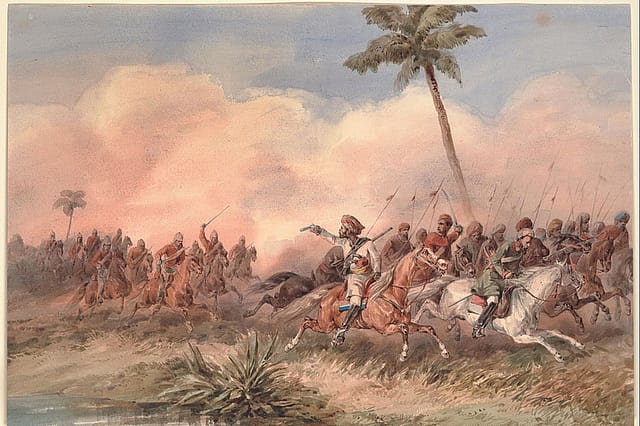

HIS RESIGNATION FOLLOWED. The Government came out with an official history of the freedom movement and Majumdar was also to publish his history privately. He also published his account of 1857—entitled The Sepoy Mutiny and the Revolt of 1857—in 1957, the centenary of the event. There is certainly much in this volume that went against prevalent and contemporary opinions on a range of issues, beginning with the vexed question of religion and communal relations. In Majumdar's view, in 1857, although Hindus and Muslims fought against the British, "we miss that real communal amity which characterises a national effort," and "the idea of a common national endeavour to free the country from the yoke of the British is conspicuous by its absence…Indeed we could hardly expect such an idea in these days…though in our national enthusiasm in later days we attributed it to them". His approach in fact showed fundamental differences with what an education ministry led then by Maulana Abul Kalam Azad would have believed.

Majumdar wrote: "It is an ominous sign of the time that Indian history is being viewed in official circles in the perspective of recent politics. The official history of the freedom movement starts with the premises that India lost independence only in the eighteenth century and thus had an experience of subjection to a foreign power for only two centuries. Real history, on the other hand teaches us that the major part of India lost independence about five centuries before and merely changed masters in the eighteenth century."

Statements such as this led to what we call today the 'Hindu Right' embracing Majumdar as one of their own. Certainly, his differences with leading historians of the 1960s and later were profound. He was often derided by opponents to his left as a 'communal' historian, and by others as a 'nationalist' (as opposed to a historian who is objective). By the same token, he is exalted by those on the right as an example of the 'right kind' of history writing that was frowned upon and therefore never given its due during the long Congress-led consensus post-1947. More moderate, if quieter voices, across the ideological spectrum saw him however, notwithstanding all his biases, for what he said he was—a historian. As an eyewitness to the polarisation that engulfed Bengal after its first partition in 1905, it is inevitable that he as a historian would look for the historical roots of contemporary divides. Looking to the deep past for the origins of present maladies comes naturally in the circumstances and we confront again the dilemma posed by Nehru of the "pure and virgin moment" being trumped by the "harlotry of the past".

But re-reading Majumdar today, we also encounter someone conscious of the perils the nationalist path posed for the historian. In an essay he wrote on the evolution of Indian historiography, his comments about its 'defect' bears repetition: "The chief defect arose from national sentiments and patriotic fervour which magnified the virtues and minimized the defects of their own people. It was partly a reaction against the undue depreciation of the Indians in the pages of British histories like those of Mill and partly an effect of the growth of national consciousness and a desire for improvement in their political status. It is a noticeable fact that the defects gained momentum with the movement for political reforms, and later, in the course of the struggle for freedom".

Majumdar went on to a more specific case: "An extreme example is furnished by KP Jayaswal. The repeated declarations of British historians that absolute despotism was the only form of Government in Ancient India provoked Indian historians who…emphasised the existence of republican and oligarchical forms of government. This reaction, was generally speaking, kept within reasonable limits of historical truth; but Jayaswal carried the whole thing to ludicrous excess in his Hindu Polity, by his theory of a Parliamentary form of Government in Ancient India, which is a replica of the British Parliament including the formal Address from the Throne etc…Similarly, historical discussions on social and religious matters are not often coloured by the orthodox views on the subject. The recent acrimonious discussion on the killing of cows shows how even clearly established facts of history are twisted to suit present views".

In the same vein Majumdar said that "conscious attempts are often made to explain away, ignore, or minimize, the harsh treatment accorded by the high caste hindus to the lower castes particularly Sudras and Candalas". Majumdar was also fond of reiterating a dictum of Jadunath Sarkar even some 50 years after it was first articulated: "I would not care whether truth is pleasant or unpleasant and in consonance with or opposed to current views. I would not mind in the least whether truth is or is not a blow to the glory of my country".

In the history Majumdar wrote of the 1857 events, what comes through is a scrupulous regard for evidence-based interpretation and possibly this may well have been the real cause of the rift with the education ministry rather than the philosophical difference of opinion about the absence or existence of Hindu-Muslim accord through history. It is striking to see Majumdar's portrayal of the iconic figures of 1857—Lakshmibai, the Rani of Jhansi; Bahadur Shah, the Mughal emperor; Nana Saheb, the deposed Maratha leader in Kanpur; and others. In retrospect, it is easy to see why the Department of Education would have found it impossible to let his account appear as the official history of 1857 on the centenary of that landmark event. Majumdar said that he had "tried to draw a faithful and realistic portrait" of these figures as their "images in popular minds are the product of romantic and patriotic sentiments rather than an objective study of historic facts". It was, he said, "his painful duty, for the sake of historical truth, to debunk these heros whose memory has been enshrined in the heart of the Indians for over half a century and who have been the object of genuine reverence as fighters for the freedom of India…none of them has any legitimate claim to such a position…."

In the case of the emperor Bahadur Shah, Majumdar wrote: "we have indisputable evidence that he was unfaithful to the cause of the Mutiny, or the War of Independence, as some would fain call it". On Nana Saheb in Kanpur, Mazumdar's verdict is harsher: "nothing…by the remotest stretch of imagination entitle(s) him to respect either as a general or as a man" as he referred to his "vain glorious character" and his "military inefficiency".

Majumdar is admiring of the Rani of Jhansi: "She was the only leader who died on the battle field in that great struggle and the valour and military strategy she displayed entitled her to a unique place in the history of that movement". But alongside this the task before the historian is to "critically discuss in a detached attitude, without prejudice and passion…how far the available evidence justifies the view that the Rani instigated the sepoys to mutiny…" After a careful dissection of the evidence, Majumdar's conclusion was that the "only possible verdict of history is therefore that the Rani of Jhansi had no share in instigating the mutiny of the sepoys in June, 1857…." His additional comment is worth noting also: "The world often shows strange bedfellows. Some Indian writers have attempted to prove, out of patriotic and national sentiments, what the English asserted out of animosity to the Rani of Jhansi." In Majumdar's account, therefore, the Rani rebelled when all other options had closed and if she could have made terms with the British she would have. However, "once she arrived at this decision she never wavered for a moment, and fought with courage, determination and skill…."

Other iconic leaders of the 1857 events are similarly dissected. The only person who comes through relatively unscathed from this clinical pathology of actions and motives is Maulvi Azimullah, a maulvi in Faizabad who "alone, among all the so called leaders of the great movement had no personal interest to serve as an incentive to rebellion. Yet from the very beginning he was an uncompromising and active enemy of the British." Elsewhere Majumdar referred to him as "one of the greatest patriots…."

Majumdar's account of 1857, or indeed much of his other works, have long been superseded by subsequent scholarship. In so far as they are useful today it is as an illustration of the period he wrote in rather than of the times he wrote about. As such, they would fall today in the realm of historiography rather than history. And yet he stands out for underlining that the historian's function is also to be a dissenter and one who forces us to think critically about the past rather than fall meekly in line with the prevalent narratives of the time. Possibly in Majumdar's estimation, the UGC template for history teaching would be deficient on this score as the search for the 'soul of the nation' may preclude other readings of the past, discount the role of evidence in historical interpretation and make the historical method into an inspirational feel-good allegory rather than a rigorous form of analysis.