The Choice

AS THE GREAT INDIAN SUMMER THRILLER reaches the finale, it has already shown us what makes democracy work in one of its most spellbinding settings. No matter what those who refuse to accept its preferences say, it's the passions and possibilities of democracy that make General Election 2024 a test of popular will. Its verdict matters, for what's at stake is the future of a nation fast shedding its accumulated inhibitions that restricted its growth and cultural expressions during its formative decades. And we wait for the mandate at a time when, elsewhere in the world in a year of almost 70 general elections, the leader diminished or the leader rearmed by his own delusions is the sight that captivates the most. For India, it is, almost by all accounts, renewal time: a leader that concentrated the Indian mind like no other in the last 10 years is seeking another term for furthering his covenant with the nation.

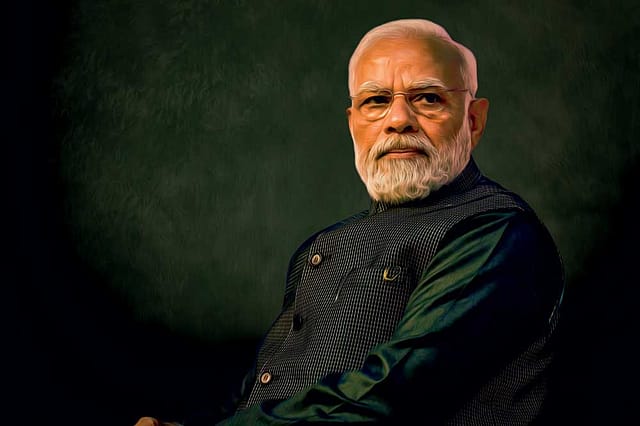

Narendra Modi, by so doing with the urgency and convictions of someone for whom every election is a self-explanation of his political being, is the one on whom India builds its conversations with the future. It's inevitable because, he has made, by maximising the imagination a public figure can afford, his own biography a prerequisite for national destiny. Modi is not the first one in politics who has achieved this feat; he is certainly the one who has kept its freshness for so long.

Few politicians possess the creative power to make themselves the most shared story and the most effective storyteller at the same time. Modi, the man who came from the middle row of a nascent political establishment, went on to turn adversity into a political advantage, and gained an easy access to the Indian mind as an administrator and leader, has become the only story that India is celebrating—and disputing—in this election.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

We need to return to 2014 when, after being India's most popular chief minister for more than a decade, Modi began his new journey as one of the most popular leaders in a democracy. Prime Minister Modi was the culmination of one of politics' longest campaigns that started from the dying embers of a riot that shook India. As chief minister, he became the model administrator in a country whose experiments with development and modernisation have consistently been marred by the worst instincts of politics. By the end of his third term, his influence had grown beyond the state, and his stature as India's chief minister was unbreachable. What set him apart from other such long-serving politicians in power was his skill and ambition to make his persona larger than his office. Modi on the stump, even as Gujarat's chief minister, campaigned for India by making the most immediate topics of the times— whether it was Islamist terror in the wake of 9/11 or the relentlessness of Pakistan's anti-India motives—his themes. There was no better instance of a state leader turning into a national choice.

Prime Minister Modi was born from the impatience of a democracy subjected to redundant models of nation-building. He stormed Delhi with a compelling argument about modernisation and cultural restoration. Once in power, he has redefined power itself, and killed the proverbial truth about the days before: power corrupts. He modified it: power legitimises change. It might have been ideology that guided his political journey, but it was the ideas of a moderniser who required no templates from the global playbook of the Right that made his power enduring. In an India punished by varying degrees of borrowed isms, some of those who were inspired by the definitive right turn expected him to play a desi version of a Reagan or Thatcher. He chose to be Modi: a gradualist, not an insurgent; a reformer whose sense of the future was in perfect harmony with his cultural indebtedness to the past. From the very beginning he understood that what works better in an unequal society like India is not replication of models but humanisation of development. His first term formalised national re-imagination with cultural confidence.

The enhanced mandate of 2019 was a validation. In the next five years the changes in the marketplace and the cultural space of India would make Modi a nationalist with unmatched clarity about his political mission: a modern nation unapologetic about its traditions. It was said that, and not always without a reason, the Right wins the economic argument at the cost of the cultural one. The Modi model is an exception. India is not only a fast-growing economy but a country with an amazing record in grassroots empowerment as well. In another time, when populism was the default position of the strong leader from the left of centre, poverty was more a slogan than a provocation for reorienting the welfare state—a time when the wretched was reduced to political fodder. If the poor and the youth and women form the demographic groundswell that sustains Modi, it only shows the magnitude of the human quotient in his modernisation project—and his ability to blend pragmatism with idealism. Call it compassionate conservatism with Indian characteristics. The globally appreciated pace of the Indian economy is powered by a higher sense of social reality.

The global statement of the Indian economy is matched by India's diplomatic resurgence. The India that hosted the G20 summit in Modi's second term was a country so sure of its place at the international high table. New Delhi has come a long way from the ideologically driven Third Worldism, with anti-Americanism as a necessary establishment attitude, to the sunlight of multilateralism with a nationalist core. A world shaken by wars and genocidal hatred of a religion has certainly tested India's international morality and diplomatic choices. There again New Delhi has succeeded in balancing national interest with the responsibility that comes with being a democracy in the fast lane. And all the while, Modi, a leader with a high democratic rating, has justified why the title of thewise man from the east is his to keep, particularly at a time when Beijing, still characterised by paranoia and extraterritorial transgression, has become the axis of unfreedom.

And one monument to the Modi legacy is a measure of how India's oldest cultural accent has acquired a new confidence. For so long, Ayodhya was the site of Hindu grievance with a backstory of invasions and vandalism. Then, one day in December, more than 30 years ago, it was the site where the secular state was on trial. And almost four years later, as India's first rightwing government took office, Ayodhya was the obvious motif of history's shift. On January 22, as Modi played the master of ceremony at the restoration of a god in a temple worthy of him, it was a testament to cultural assertion in a country where the Hindu,under the attack of jargon like majoritarianism,was conditioned to be on the defensive.The normalisation of nationalism with a cultural adjective is not aggression but the acceptance of a nation's civilisational ancestry—and you can't grudge the most feted homecoming of a displaced god—or a prime minister who played host.

The theme of restoration runs through the story of Modi in power, and in the last five years it has acquired a national urgency with popular endorsement. The opposition only reminds India why he is the natural—and necessary—claimant to the country's next five years. Can we dispute the fact that I.N.D.I.A. has miserably failed to reveal the India they stand for? What they revealed, with consistent incoherence, is that they have nothing to offer except a posturing that India is bound to reject: Anyone but Modi. It is Modi versus the pastiches of non-Modi. The feeble opposition to Modi comes from insufficient political imagination and abundant intellectual denialism. Which only shows how Narendra Modi has become a national habit.

For securing national stability with the strength of leadership, accelerating growth with a social conscience, placing India at the global high table without compromising on national interest, and for bringing the cultural ancestry of a people back to the political mainstream, Narendra Modi should be the choice of India on June 4.